“No One Stays Good in This World”: A Review of Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice

Since debuting in 1938, Superman has confronted many imposing adversaries, including Lex Luthor – a formidable foe whether characterized as an obsessed bald scientist or scheming corporate tycoon; the alien computer Brainiac; Terra-Man, armed with an endless array of ingenious weapons; several Kryptonian supervillains who survived the destruction of their planet in the Phantom Zone; and the ancient Kryptonian monster Doomsday, who once succeeded in killing the Man of Steel. But now, in the twenty-first century, the venerable superhero is finally facing his most dangerous and destructive opponent …. Zack Snyder.

Since debuting in 1938, Superman has confronted many imposing adversaries, including Lex Luthor – a formidable foe whether characterized as an obsessed bald scientist or scheming corporate tycoon; the alien computer Brainiac; Terra-Man, armed with an endless array of ingenious weapons; several Kryptonian supervillains who survived the destruction of their planet in the Phantom Zone; and the ancient Kryptonian monster Doomsday, who once succeeded in killing the Man of Steel. But now, in the twenty-first century, the venerable superhero is finally facing his most dangerous and destructive opponent …. Zack Snyder.

Did you think I was talking about Batman? But in the film Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice, the Dark Knight merely becomes one of the innumerable individuals who have briefly threatened Superman by brandishing a piece of kryptonite, the only substance in the universe which can destroy him. In contrast, Snyder is equipped with Hollywood’s most valued superpower – the ability to generate huge profits – and as long as his Superman films continue to make money, he can do whatever he likes with the character, aided and abetted by longstanding partners in crime like writer David S. Goyer.

While considering Snyder and Goyer’s previous assault on Superman, Man of Steel (2013 – review here), I chiefly objected to their apparent resolve to transform this shy, benevolent hero into a killing machine, perfectly willing to slaughter the evil General Zod (and thousands of innocent bystanders) in pursuing his commitment to truth, justice, and the American way. Perhaps in response to others’ negative reactions, in this film they somewhat retreat from that position, yet in a manner that further diminishes the character: Henry Cavill’s Superman, it now transpires, is basically stupid. He thumb-fistedly keeps trying to do the right thing but never seems to realize that his good deeds can cause collateral damage. Further, he cannot recognize that, despite his occasional legal transgressions, Batman (Ben Affleck) is essentially a force for good; he further fails to understand that vanishing from sight after being at the scene of a disaster might inspire suspicions about his possible involvement (a point made by one of the celebrities who make cameo appearances as themselves, crusading prosecutor Nancy Grace); and he must rely on his bright girlfriend Lois Lane (Amy Adams) to deduce that Lex Luthor (Jesse Eisenberg) is engaged in an elaborate conspiracy to blacken his reputation and manipulate him into a fatal confrontation.

All of this relates to another way in which Snyder’s version of Superman is dishearteningly different from the character that readers and filmgoers have long admired: except for a brief, clumsily unpersuasive romantic moment near the beginning of the film, Cavill never seems to be happy. He never enjoys being Superman; he never expresses the delight in his extraordinary powers that classic Supermen like George Reeves, Christopher Reeve, and Dean Cain so effortlessly conveyed. And the main reason for this is that this Superman just isn’t smart enough to figure out how to be Superman. Everyone in his life keeps telling him what he should be doing – Lois Lane, his mother (Diane Lane), even his dead father (Kevin Costner) in a vision – but all their good advice proves ineffectual, as their student keeps failing to learn the lessons they are repeating.

Given his diminished capacity, one might expect that Snyder and company would avoid the efforts, visible in the first film (and criticized by yours truly), to portray Superman as a Christ figure. In fact, they intensify them, as Cavill again poses as Jesus Christ on the cross; the film’s overbearing soundtrack regularly features voices suggesting heavenly choirs; Luthor repeatedly refers to him as a “god”; one television commentator describes him as a “savior”; his mother tells him that one role he might play for people is being their “angel”; and after he saves a girl in Juarez, Mexico, during a Day of the Dead celebration, people worshipfully surround him, extending their arms to touch their miraculous rescuer. The film’s most obvious gesture in likening Superman to Jesus Christ should not be explicitly revealed, but it may be reflected in, of all things, its release date. Many were surprised when producers decided to release this much-anticipated film in March, instead of the usual time when such films appear, summer or the holiday season; perhaps this suggested some concern that the film wasn’t strong enough to compete with other upcoming blockbusters. But someone may have decided that it would be especially fitting to have this particular film open on Good Friday, and conclude its opening weekend on Easter Sunday, considering what happened on the first Good Friday, and what happened on the first Easter Sunday. I will say no more.

As for the other characters who are traditionally elements of the Superman mythos: Adams’s Lois Lane is still a bright spot, but Laurence Fishburne as editor Perry White remains an underutilized resource, his only role here being to express understandable frustration with an obdurate reporter who pursues his own obsessions instead of completing his assignments. The credits insist that an actor named Michael Cassidy is playing Jimmy Olsen, but while I suspect he is the young man once observed in the Daily Planet office, this key character is effectively invisible, supplanted by the bland, underdeveloped Jennie (Rebecca Buller). But by far Snyder’s most risible violation of the canon is Jesse Eisenberg’s bizarre Lex Luthor. Before watching this film, I would have insisted that no one could possibly do a worse job of playing Lex Luthor than Gene Hackman, who wounded three films with his egregious misinterpretation of the character. However, Eisenberg rises to the challenge, definitively establishing himself as The Worst Lex Luthor of All Time. One cannot blame the actor, though, since he manifestly was merely playing the part assigned to him by Goyer and Chris Terrio’s deeply flawed script. The problem is not simply that this Luthor is incongruously portrayed as an overgrown child, that he consistently seems utterly and unpleasantly insane, that none of his purported witticisms are actually funny, or that his motives for attacking Superman remain bafflingly unclear. No, the problem is that, unlike all the other Luthors, this one isn’t a genius, scientific or otherwise; he doesn’t even seem to possess a normal amount of intelligence. He temporarily succeeds in his efforts only because he is slightly smarter than his extremely dense adversaries, Superman and Batman. (Yes, as you’ve figured out, this film represents a classic example of what James Blish termed an “idiot plot” – a plot kept in motion solely because every character involved is an idiot.)

But I have not yet addressed how Snyder has distorted and debased the other iconic character entrusted to his care, Batman. Since Christopher Nolan, who directed three excellent Batman films, was involved with this film as an executive producer, one might imagine that the top-billed Dark Knight would be handled appropriately, and they cast an excellent actor, Ben Affleck, who clearly could have been a superb Batman had he been handed a different script. However, while it has recently been common to portray Batman as sometimes on the verge of insanity, permanently traumatized by witnessing his parents’ murder as a child, this film presents a Batman who has completely gone off the deep end, ready for the loony bin. I mean, he has starting carrying a branding iron to brand street criminals with a bat-symbol, which is pointlessly vindictive to say the least, and he allows an understandable concern about the negative effects of Superman’s behavior to evolve into a sick determination to literally assassinate the Man of Steel on the stated grounds that there is a “one percent chance” he might turn on humanity and destroy the Earth. (Hmmmm …. today, there is a “one percent chance” that several people – the national leaders controlling nuclear arsenals – might turn on humanity and destroy the Earth, but no sane person is proposing to assassinate them.) Furthermore, this attitude is not only crazy, but utterly incompatible with all previous portrayals of Batman; yes, the Dark Knight doesn’t like criminals, but he has never, never been dedicated to slaughtering them. In the scene where Batman is preparing to kill Superman with visible glee, then, we observe a hero being shifted 180 degrees from his original character.

Perhaps, though, the filmmakers might explain the apparent degradation of this once-noble characters by referencing another legendary story that can be connected to Batman’s saga. He is regularly described as the Dark Knight, and the film announces “the knight is here”; he literally dons a suit of armor (making him look more like Iron Man than Batman) to do battle with Superman; and in the opening scene that retells the story of his parents’ murder, we learn they were gunned down in 1981 after the family had just seen the movie Excalibur (1981) – one of many films that retells the story of the virtuous knights of Camelot, Arthur and Lancelot, who not incidentally end up warring against each other. And, if such admirable heroes could become foes, the argument would go, the same thing might happen to Superman and Batman.

Still, unlike Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur (1485), Hollywood films – particularly Hollywood films with announced sequels featuring their protagonists – must have happy endings, with all heroes alive and well, which means that something must happen to make Batman realize that Superman is really a good guy, so they can fulfill their destiny and become allies. That reversal proves to be amazingly abrupt – literally five minutes after he almost kills Superman, Batman describes himself to Superman’s mother as the hero’s “friend” – and as best one can determine, incredibly, the change occurs when Batman learns that the name of Superman’s mother is Martha – which is also the name of his mother. And hey, the dim-witted Dark Knight presumably reasoned, anybody whose mother’s name is Martha has to be wonderful, right? (Thus, if Lex Luthor had really been bright, he would have told Batman that his mother’s name was Martha, and the two would have ended up as best buddies.)

The film’s other character from the Batman mythos, Alfred (Jeremy Irons), is more likable, inasmuch as he mildly objects to Batman’s increasingly questionable behavior; but while Alfred regularly assists Batman in various ways, Snyder, Terrio, and Goyer apparently forgot that the character is always, first and foremost, a butler. This Alfred, though, is never observed doing what butlers should be doing, picking up his master’s clothes and bringing him a cup of tea. Noting the absence of Batman’s other traditional partner, Commissioner Gordon, and a plot involving two of Superman’s villains and none of Batman’s villains (though the Joker is referenced when Batman states that Gotham City has “a bad history of freaks dressed like clowns”), it becomes apparent that, while Batman’s name comes first in the title, this is essentially Superman’s film, taking place in Superman’s world, a direct sequel to Man of Steel that conveniently ignores the conclusion of the last Batman film, The Dark Knight Rises (2012 – review here).

There is another way in which Superman dominates this film: while it is noted that Batman has spent “twenty years” catching criminals, nobody in the film pays any attention to him, and Perry White announces that he will not waste any space in his newspaper covering the Dark Knight’s activities. Yet everyone is obsessively focused on Superman, including a number of actual celebrities who appear in the film as themselves, talking about Superman, including the aforementioned Nancy Grace, physicist Neal deGrasse Tyson, filmmaker Vikram Gandhi, commentator Andrew Sullivan, and broadcast journalists Kent Shocknek, Charlie Rose, Soledad O’Brien, and Anderson Cooper; and when fictional senator June Finch (Holly Hunter) invites Superman to a hearing, a real senator – Patrick Leahy of Vermont – shows up, playing “Senator Purrington.” All of this star power directed at Superman contributes to the sense that he, not Batman, is the film’s most noteworthy hero, and it also illustrates the rising status of superheroes in popular culture; because, if someone had made a Batman v Superman movie in the 1960s, I am confident that Walter Cronkite and Senator Everett Dirksen would never have agreed to appear in it.

Whenever he confronts criticisms of his alterations to the canon, Snyder brushes them aside, on the grounds that they only represent the antiquated conservatism of diehard fans irrationally resistant to change. Classic characters, he might say, need to adjust to contemporary conditions, need to be rethought and reinvigorated from a fresh perspective, and there is certainly some truth in that. (Perhaps Snyder intended to convey that point when Perry White explains that he will not cover Batman because “It’s not 1938” – the year when the Superman character first appeared.) Yet all enduring heroes also have core characteristics that must be respected, and that isn’t occurring in this film; for when you portray Superman as a clumsy moron, and Batman as a homicidal psychopath, you are not merely reinterpreting these characters, but you are eliminating the very reasons why they became popular in the first place.

Still, as if to counter complaints that he has been insufficiently respectful of Superman’s and Batman’s history, Snyder carefully concludes this film with a long list of “Special Thanks” to several of the editors, writers, and artists responsible for their comic book adventures, including Jim Aparo, John Byrne, Gerry Conway, Gardner Fox, Carmine Infantino, Frank Miller, Jerry Ordway, George Pérez, Curt Swan, Len Wein, Mort Weisinger, and Marv Wolfman. But this is an empty gesture; to show genuine respect for the people who long chronicled the adventures of Superman and Batman, filmmakers should make a film based on one of their stories, instead of (as they always do) making up their own stories. (This demonstrates, in a way, the astounding arrogance of Hollywood: the DC and Marvel superheroes have starred in thousands of comic book adventures, some of them extending to hundreds of pages and providing more than enough of the epic scope that contemporary filmmakers crave; but screenwriters always assume that they are smart enough to simply take those characters and come up with their own, better stories, even though the results, more often than not, are so clumsy and contrived – like this film’s plot – that they would never be deemed good enough for a comic book.)

It should be obvious by now that I disliked this film’s approach to Superman and Batman and generally did not enjoy watching it; yet, after two hours of routine violence and tedious exposition, there comes a time when this misbegotten film suddenly sputters to life and becomes a satisfying viewing experience – and that is when a third hero, Wonder Woman (Gal Gadot), finally appears. This is not a surprise, because the previews featured the scene where she, Superman, and Batman stood together for the first time; this is unquestionably the emotional highlight of the film, a moment that fans of the DC universe have dreamed about for decades, and a scene that should have been part of a film that was better than this one. And why is it so exhilarating to see her? Because, for the first time in the film, we are presented with a hero that we can actually like, a hero that we know, from her earlier appearances as Diana Prince, is both savvy and sympathetic. When she starts battling against the film’s final and fiercest foe, we are actively rooting for her, hoping that she succeeds, while we are far less concerned about the possible success of the perpetually confused Superman or the dangerously demented Batman; and Gadot seems absolutely perfect for the part. Few filmgoers, I suspect, will walk out of the theatre eagerly anticipating another film featuring Cavill’s Superman or Affleck’s Batman; but if they are like me, they will very much want to see more of Gadot’s Wonder Woman.

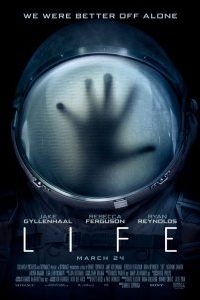

As for the other future members of the Justice League that we knew would be appearing, the film’s story did provide a perfect opportunity for Aquaman (Jason Momoa) to show up and contribute to the cause, yet the necessary aquatic rescue was instead performed by Superman, and Aquaman, like the Flash (Ezra Miller) and Cyborg (Ray Fisher), appears only fleetingly in a film clip observed by Wonder Woman. And while Ryan Reynolds’s version of Green Lantern (2011) was hardly a triumph (review here), many will be saddened by the decision to exclude this founding member of the Justice League from this film and future films. Still, fans can anticipate seeing all the other heroes in announced future Justice League films and their own films – assuming that Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice is sufficiently profitable as to ensure their production. (I have my doubts, but there’s no accounting for taste.)

As if to explain why its heroes so often seem to be acting unheroically, the film states at one point that “No One Stays Good in This World” – and perhaps, as popular characters are rebooted again and again and again, there is a natural tendency for them to become less good, in both their moral values and their films’ quality. Yet the film also advances the idea that it is a “feeling of powerlessness” that “turns good men cruel.” And the film does suggest that, despite their immense prowess, its superheroes are indeed become less and less powerful: Batman suggests at one point that his war against crime is essentially futile – “criminals are like weeds; pull one up, another grows in its place”; Senator Finch wishes to impose some sort of governmental control on Superman’s actions; and despite their best efforts, these heroes are never able to prevent vast urban areas from being devastated by the menace du jour. Even as popular culture increasingly valorizes superheroes, then, those heroes may be becoming grouchy and violent because the residents of a complex world are less and less able to believe in the efficacy of superheroes – except, perhaps, as a way to bolster the profits of Hollywood filmmakers.