Ian McDonald: On Xenoforming

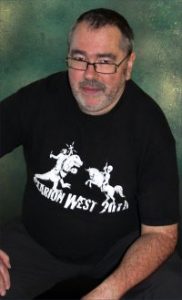

Ian Neil McDonald was born March 31, 1960 in Manchester England. He moved to Northern Ireland at age five and has lived there ever since. He attended Bangor Grammar School and worked as head of development for a TV production company.

McDonald began publishing SF with ‘‘The Island of the Dead’’ (1982), and his stories soon began to appear regularly in Asimov’s, Interzone, and other magazines. His novels include Locus Award-winning debut Desolation Road (1988) and related book Ares Express (2001); Out on Blue Six (1989); Philip K. Dick Award-winning King of Morning, Queen of Day (1991); Hearts, Hands and Voices (1992; as The Broken Land in the US); Necroville (1994; as Terminal Cafe in the US); The Chaga series: Chaga (1995; as Evolution’s Shore in the US), Kirinya (1998), and Sturgeon Award winning novella Tendeléo’s Story (2000); Sacrifice of Fools (1996); BSFA Award winner and Clarke and Hugo Award finalist River of Gods (2004); Hugo and Nebula Award finalist and BSFA winner Brasyl (2007); and Hugo and Clarke Award nominee and BSFA and Campbell Memorial Award winner The Dervish House (2010). He began his YA Everness series with Planesrunner (2010), and it continues with Be My Enemy (2013) and Empress of the Sun (2014). Adult novels Hopeland and Luna (first in a duology) are forthcoming.

Notable short fiction includes Nebula Award nominee ‘‘Unfinished Portrait of the King of Pain by Van Gogh’’ (1988); BSFA Award winner ‘‘Innocents’’ (1993); Hugo Award finalists ‘‘The Little Goddess’’ (2005), ‘‘The Tear’’ (2008), and ‘‘Vishnu at the Cat Circus’’ (2009); and Hugo Award winner ‘‘The Djinn’s Wife’’ (2006). Some of his short fiction is collected in Empire Dreams (1988), Speaking in Tongues (1992), and Cyberadad Days (2009), a British Fantasy Award finalist and recipient of a Philip K. Dick Award special citation. He wrote graphic novel Kling Klang Klatch (1992, illustrated by David Lyttleton).

McDonald lives in Belfast, Northern Ireland with his partner, Enid Crowe.

Excerpts from the interview:

‘‘For the Everness books, I came up with the image of an airship that can travel between parallel universes, which is probably something every writer’s thought of at some point, and I just followed it through. It was a nice break to do something different. Steampunk without steam. Teslapunk. Steampunk without the messed-around Victorian values. Real Victorians would be completely alien! I didn’t want to get stuck doing the same SF books over and over, successful though they may be. I didn’t want to keep writing books about the developing economy of the year – India, Brazil. I could feel myself getting trapped in that.

‘‘There’s the whole Northern Ireland thing, living in a marginal country, which doesn’t seem that science fictional – I’m drawn to other marginal places. When I write about a place, I always go there. (I’m doing a book about the moon, which is problematic. You should see the flyer miles I get with that.) I try to be honest about my experience of the place, though one can lob grenades of appropriation around and back again. If I haven’t gone there, and I haven’t seen stuff and noticed little details, and put some money into the economy as well, I don’t feel I can write about it with any kind of degree of honesty, for myself. Of course I get things wrong – but I can write about what happens at the bottom of my street and get things wrong, too.

‘‘Colonialism is a kind of reverse terraforming in a sense – the southern hemisphere being terraformed into somebody else’s terra. Xenoforming, that’s the word. There was a display in our local museum and it was a little diorama of the seabed in the Permian epoch. That was truly bizarre – it looked like an alien world. What if that alien world was part of our world? What if the alien invasion wasn’t UFOs arriving over the White House, but foreigners arriving in the southern hemisphere at Kilimanjaro?”

…

‘‘My next books are Luna parts one and two, a duology set on a moon base – Game of Domes. In the Luna books, I’m still writing about developing economies, it’s just that this one happens to be on the moon, about 2089. It was basically Gary K. Wolfe who was responsible for it. On an ancient Coode Street podcast about invigorating stale subgenres in science fiction, he said he’d love to see a new take on the moonbase story. I don’t know why, but I’ve always loved moon stories. John Varley did one, Steel Beach. I thought about it, and Enid, my partner, was watching TV, the new version of Dallas. It wasn’t very good, but the old version was great. My book is Dallas on the moon, so it’s got five big industrial family corps on the moon, called the five dragons, and it’s about their intrigues and battles. It’s also developing in parallel as a TV project with a company I’ve worked with before. There’s a gap in the market for an SF series that doesn’t look like science fiction, if you know what I mean.

‘‘There are a couple of kickers that keep the story running along. On the moon there’s no criminal law, there’s only contract law. Everything is negotiable in some form or another. You can be married to three different people at the same time with three different contracts; they don’t have to live with you. Every part of life is negotiated. There’s also a ticking clock: if you’re on the moon for more than two years, your bone structure and musculature will degenerate to the point to where it’s not safe to go back to Earth again, so everyone who goes there to work has to decide, ‘Do I stay or do I go?’ And there’s corporate intrigue, with a family matriarch getting old but not ready to pass, because there will be a power vacuum. There are battling brothers, basically the Thor/Loki relationship, with the charismatic older brother and the clever younger one. It’s a lot of fun to do. I watched the hell out of The Godfather several times, parts one and two. It’s the same structure, really. There’s been a first look at the world of Luna already: Jonathan published a story ‘The Fifth Dragon’ in his Reach for Infinity anthology, which is part of this world.”

‘‘There are a couple of kickers that keep the story running along. On the moon there’s no criminal law, there’s only contract law. Everything is negotiable in some form or another. You can be married to three different people at the same time with three different contracts; they don’t have to live with you. Every part of life is negotiated. There’s also a ticking clock: if you’re on the moon for more than two years, your bone structure and musculature will degenerate to the point to where it’s not safe to go back to Earth again, so everyone who goes there to work has to decide, ‘Do I stay or do I go?’ And there’s corporate intrigue, with a family matriarch getting old but not ready to pass, because there will be a power vacuum. There are battling brothers, basically the Thor/Loki relationship, with the charismatic older brother and the clever younger one. It’s a lot of fun to do. I watched the hell out of The Godfather several times, parts one and two. It’s the same structure, really. There’s been a first look at the world of Luna already: Jonathan published a story ‘The Fifth Dragon’ in his Reach for Infinity anthology, which is part of this world.”

…

‘‘The kids’ books series gives me a chance to play off the leash a bit. Though I enjoy the discipline of more realistic science fiction, if that’s not a contradiction in terms. It’s the little domestic bits I enjoy writing. The bits where you run around blowing things up I find a bit boring to write. I’ve had inquiries about adapting Planesrunner for television. It is aimed at the Dr. Who audience quite deliberately. The series has the go-anywhere machine, which is what the Tardis is, but I also wanted a crew like you have in Star Trek. That sounds awfully cynical. But it’s fun to do. I giggle when I write bits. It’s ‘parallel universe of the week,’ but there is a plot in the background.”

…

‘‘The other upcoming book I have is a project that’s been rolling around for about 15 years now, called Hopeland. This is the science fictional equivalent of the kind of thing Neil Gaiman does with fantasy. That’s the nearest I can describe it. He roots his work very firmly in this world, and does little bits of weird in the everyday. Or like Graham Joyce, the kind of thing he does. We almost sold it as a mainstream novel – it could pass as one. I’ve been writing about very big societies, and now I’m writing about very small societies. The lunar societies have maybe three, four million people. It’s not a very big world. Hopeland is even smaller. It takes place inside a family. The premise is that back in the 1920s this guy invented a new kind of family structure that isn’t the nuclear family. It’s the family you never need to leave or never have to leave, the constellation family, which constantly adds new members. The idea is, it’s a social unit that will last for 10,000 years. Simon Spanton, my editor at Gollancz, loved it. I sent him about six chapters, and he said, ‘Why didn’t you tell me about this three years ago? What’s your agent been doing? It’s great!’

‘‘Things brew, and if I don’t do something about them they’ll disappear. Hopeland came out of a magazine article I saw in 2000, so it’s been in there about 14 years, just waiting for me to have the courage to do something about it.”