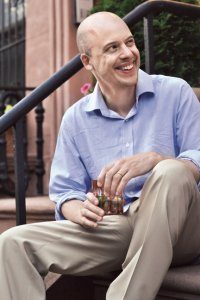

Sheila Williams: New Directions

Sheila Elizabeth Williams was born September 27, 1956 in Springfield MA. She grew up in western Massachusetts and attended Elmira College in upstate New York, doing a year abroad at the London School of Economics, and graduating in 1978 with a degree in philosophy. She earned her master’s degree in philosophy at Washington University in St. Louis MO in 1982.

Sheila Elizabeth Williams was born September 27, 1956 in Springfield MA. She grew up in western Massachusetts and attended Elmira College in upstate New York, doing a year abroad at the London School of Economics, and graduating in 1978 with a degree in philosophy. She earned her master’s degree in philosophy at Washington University in St. Louis MO in 1982.

Williams began working in the magazine business in 1981, first in a subsidiary rights department, then as an assistant at Asimov’s, where she was soon promoted to managing editor. She became editor in 2004 when Gardner Dozois retired.

Williams has co-edited many anthologies, most collecting stories from Asimov’s, including Tales from Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine (1986) and Intergalactic Mercenaries (1996) with Cynthia Manson; Why I Left Harry’s All Night Hamburgers and Other Stories (1990) with Charles Ardai; Isaac Asimov’s Robots (1991), Isaac Asimov’s Earth (1992), Isaac Asimov’s Cyberdreams (1994), Isaac Asimov’s Skin Deep (1995), Isaac Asimov’s Ghosts (1995), Isaac Asimov’s Vampires (1996), Isaac Asimov’s Moons (1997), Isaac Asimov’s Christmas (1997), Isaac Asimov’s Camelot (1998), Isaac Asimov’s Detectives (1998), Isaac Asimov’s Valentines (1999), Isaac Asimov’s Werewolves (1999), Isaac Asimov’s Solar System (1999), Isaac Asimov’s Mother’s Day (2000), Isaac Asimov’s Utopias (2000), Isaac Asimov’s Father’s Day (2001), and Isaac Asimov’s Halloween (2001), all with Gardner Dozois. She co-edited A Woman’s Liberation: A Choice of Futures By and About Women (2001) with Connie Willis.

Alone she edited The Loch Moose Monster: More Stories from Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine (1993), Hugo and Nebula Award Winners from Asimov’s Science Fiction (1995), Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine: 30th Anniversary Anthology (2007) and Enter a Future: Fantastic Tales from Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine (2011).

Williams has been a Hugo Award finalist for editing every year since 2006, and won in 2011 and 2012. She lives in New York with husband David Bruce and their two daughters.

Excerpts from the interview:

‘‘I fell in love with science fiction before I knew there was a term called ‘science fiction.’ When I was five, my father told me the story of the Princess of Mars. He only had copies of Warlord of Mars and Gods of Mars, which he read to me. But he told me about Dejah Thoris and John Carter, and that was it. After that, I read it all myself. My father had a membership in the Science Fiction Book Club, so books would come every month. I read everything we had, and everything in the library. After a while I discovered that, in the library, everything I loved had spaceships on the spines – what I loved was mostly science fiction.

‘‘My father was not a big fan of fantasy, except Edgar Rice Burroughs. I loved Burroughs, too. I read all the Tarzan books. My mother was horrified that I was reading all of these books. I used to hide when she wanted me to do chores. I’d hide with my Tarzan of the Apes books behind the easy chair, and I discovered that was where she hid all of the Halloween candy. She was calling me, and I was hiding out with Tarzan and eating all the candy.”

…

‘‘Iris told me, ‘We have to talk. I have good news and bad news. The bad news is, you know and I know that you’re not really happy at this job.’ I thought, ‘Oh, God, I’m going to be fired.’ She said, ‘But the good news is, the editorial assistant is leaving Asimov’s. Would you be interested?’ I said, ‘Editorial assistant at Asimov’s?’ She said, ‘Don’t be so happy you’re leaving me!’

‘‘This happened about three months into my job, and for three months after that Iris couldn’t find anyone to replace me. I was suddenly perfect, after not being quite good enough. After three months, the assistant at Asimov’s left. Kathleen Maloney said, ‘One of us is getting a temp, and it’s not going to be me.’ Iris hired the next person she interviewed, and I went to work for Asimov’s as the editorial assistant. Three weeks later Kathleen resigned to become the acquisitions editor at Times Mirror, and the people in charge said, ‘Sheila, you’re going to have to be managing editor. We know you’re very shy, but you have to get out there and be aggressive and talk to people.’ (I didn’t officially get the title of managing editor for three more years.) I’ve been at Asimov’s for 31 years now.

‘‘I ended up becoming very close to Isaac. It was a wonderful part of my life. He’d come in on Tuesday mornings to drop off an editorial or a letters column, or he’d just sit and chat. He would stay about 20 minutes, half an hour at the most. He’d also make the rounds to Doubleday that same morning. He was a joy – so much fun. Usually he was in a great mood and was very funny. Sometimes he’d be down, but he always enjoyed coming in to see us. He’d perk up when he talked with us.

‘‘Isaac never wanted to be editorial director. He was clear that editors would be hired who knew their jobs, and he did not want to be involved in the process of purchasing material. On rare occasions, Shawna would give him some stories to read that she thought were way over the edge. He would almost always say, ‘I think we should go ahead.’ I think once or twice he said, ‘This might really be questionable.’ And she wouldn’t buy them. She did not have to do that. He was a wonderful sounding board, but he wasn’t making final decisions.”

…

‘‘In some ways, working at the magazine now is still very similar. We still publish things that get us in trouble all the time. We don’t know what’s going to get us in trouble, or who with. That’s the whole nature of magazine publishing. It’s very exciting to be a magazine editor, because you know someone’s going to get mad at you sometime. You don’t know when or who or whether it will be someone on the left or the right – but someone’s going to be mad. I find that kind of exhilarating, and a little bit nerve-wracking. I don’t set out to upset anyone, but we want to break ground. The magazine is my magazine. It’s stories I like. We’re out to explore new directions. I don’t think that any editor at Asimov’s was afraid of publishing women or anyone from any particular background that wasn’t the traditional angle. But there’s been a fantastic wonderful explosion of talent from diverse backgrounds recently. Fiction in general can only benefit from that.”

…

‘‘I’m not looking for trends. I’m not trying to shape the field in any way. It’s not my goal to tell people what to read. I’m going to shape Asimov’s because it’s my magazine. Basically, I’m the ideal Asimov’s reader. Sometimes I see reviewers say a story should have been in Analog or F&SF, and I say, ‘No, an Asimov’s story is what I say it is.’ So far people have responded well to my selections. I’m very happy with it, as are the people at Penny Press and Dell Magazines.”