Isobelle Carmody: Chronicles

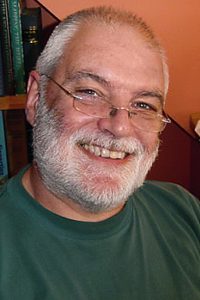

Isobelle Jane Carmody was born June 16, 1958 in Wangeratta Australia. She moved to Melbourne at age five, but grew up mostly in Geelong. She studied journalism at university, and worked as a feature reporter for the Geelong Advertiser before being published as a fiction writer.

Isobelle Jane Carmody was born June 16, 1958 in Wangeratta Australia. She moved to Melbourne at age five, but grew up mostly in Geelong. She studied journalism at university, and worked as a feature reporter for the Geelong Advertiser before being published as a fiction writer.

She is best known for her YA SF series the Obernewtyn Chronicles, which includes Obernewtyn (1987), The Farseekers (1990), Ashling (1995), The Keeping Place (2000), and The Stone Key (2008), with concluding volume The Red Queen forthcoming. Her Legendsong fantasy series includes Darkfall (1998), Darksong (2002), and the forthcoming Darkbane, and the Gateway Trilogy is Billy Thunder and the Night Gate (2002; as Night Gate in the US, 2005), The Winter Door (2003), and the forthcoming Firecat’s Dream. The Little Fur series, for younger readers, includes The Legend of Little Fur (2005), A Fox Called Sorrow (2006), A Mystery of Wolves (2007), and A Riddle of Green (2008). Standalone novels include Scatterlings (1991), The Gathering (1993), and Aurealis Award winners Greylands (1997) and Alyzon Whitestarr (2005). She has also contributed to the shared world Quentaris Chronicles, and has written a number of picture books.

Her story ‘‘The Pumpkin-Eater’’ (1995) was on the Tiptree Award longlist, and Dreamwalker (2001, a graphic novel hybrid illustrated by Steven Woolman) won an Aurealis Award for best YA short story. Some of her short fiction has been collected in Aurealis Award winner Green Monkey Dreams (1996) and Metro Winds (2012).

Carmody divides her time between living in Australia and Prague in the Czech Republic.

Excerpts from the interview:

‘‘When I started work on what would turn out to be Obernewtyn, the first Chronicle, at age 14, for me it wasn’t a book I was writing for publication; it was a story I was writing for myself. The world in which real books were written may as well have been on Venus. If you’d asked me back then, I probably would have thought authors were all famous dead people! I would write for solace, for comfort, and to work things out.

‘‘When I started work on what would turn out to be Obernewtyn, the first Chronicle, at age 14, for me it wasn’t a book I was writing for publication; it was a story I was writing for myself. The world in which real books were written may as well have been on Venus. If you’d asked me back then, I probably would have thought authors were all famous dead people! I would write for solace, for comfort, and to work things out.

‘‘Being the oldest, I was cleaning up and cooking, making beds and making lunches. It was just strictly survival. And I used to tell stories to my brothers and sisters as a way of keeping control of them. That’s how writing began, as story-telling, and I loved it. I loved acting out things, and directing my siblings to act out bits of the story, like some kind of demonic Steven Spielberg. When I started writing things down, first of all it was just to remember what I was telling them.

‘‘Writing things down stopped story-telling being this outward journey to an audience – my brothers and sisters – and became this intensely private activity, I was addicted to it immediately. I was suddenly inside the story. I was a misfit longing to find people like myself without having to change. Elspeth, heroine of the Chronicles, doesn’t have a sense of destiny. All my feelings of uncertainty, my longing to be able to do something important and significant, were poured into her. I couldn’t have articulated that at 14, but looking back now, I can see it.”

…

‘‘I think if you look at any writer’s body of work, underneath you can find they’re asking one or two really serious philosophical questions. For me, the big question was, ‘Why do people do the things they do?’ I was wondering, ‘Why did that drunk driver in the car with him kill my dad?’ My dad said, ‘Stop the car,’ and he didn’t stop and ended up killing my dad and a man whose wife was in hospital having a baby. At the time, I didn’t know why I was wounded, but that’s a decisive knowledge now. I was a quiet kid, not nasty or snarky, yet other kids used to beat me up. Why? Wondering about that poured into the Chronicles, as well as a larger question that was just a reflection of the smaller one: ‘Is it possible for human beings to evolve, ethically and morally?’ So that’s what the Obernewtyn Chronicles are trying to work out: if I can believe that human beings can get better.

‘‘I think if you look at any writer’s body of work, underneath you can find they’re asking one or two really serious philosophical questions. For me, the big question was, ‘Why do people do the things they do?’ I was wondering, ‘Why did that drunk driver in the car with him kill my dad?’ My dad said, ‘Stop the car,’ and he didn’t stop and ended up killing my dad and a man whose wife was in hospital having a baby. At the time, I didn’t know why I was wounded, but that’s a decisive knowledge now. I was a quiet kid, not nasty or snarky, yet other kids used to beat me up. Why? Wondering about that poured into the Chronicles, as well as a larger question that was just a reflection of the smaller one: ‘Is it possible for human beings to evolve, ethically and morally?’ So that’s what the Obernewtyn Chronicles are trying to work out: if I can believe that human beings can get better.

…

‘‘There’s some confusion out there because the series has taken me so long to write, and I want people to know that there will be an end to it. The last book is the one I’m writing now, The Red Queen. I’ve got something like 700 pages so far. I really want to stand against the pressure of the publishers breathing down my neck, to finish it as I want. To take the time I need to do that well, but it is a battle. They always start off, ‘But your readers really want the book!’ That’s true – I mean I hope It’s true and the letters and e-mails say that. But the publishers’ desire seems not to be to have the best book, but to have the book finished and ready to go; they think in terms of marketing. Even the angrier readers will calm down and empathise when we start to talk about why the books take the length of time they do to create. Faced with a real person with a real life who writes, they get it. That’s the series they love, and they have to wait until the author finishes it. Whether it’s George R.R. Martin or me or Tolkien, some of us take longer.”

…

‘‘I think I’d like to call myself, in future, a slipstream author. (I’ve recently started a blog, called ‘The Slipstream’.) It’s ‘the fiction of the strange.’ After I finish The Red Queen, I’ll be working on something much closer to reality, but with one weird streak – that’s how I think of slipstream as a genre – as something close to reality. It appears to be a murder, so in a way the book is also a murder mystery as well, and I love that genre, too, though I have never written anything that would fit into it before. I’m excited about trying something new. You have to, as a writer. You have to push yourself, and find new boundaries.’’