Lois Tilton reviews Short Fiction, early February

A very mixed set of publications here, with the debut issue of a new zine. No Good Story award this time.

Publications Reviewed

- F&SF, Mar/Apr 2013

- Interzone #244, Jan-Feb 2013

- Clarkesworld, February 2013

- Waylines, January 2013

- Apex Magazine, February 2013

- “Dead on Arrival” by Crystal Lynn Hilbert

F&SF, Mar/Apr 2013

An inferior issue. A couple of the shorter stories were the best, but no real award-winners here.

“Among Friends” by Deborah J Ross

Quaker Thomas Covington assists a fugitive slave, as he has done before, and soon the expected slave-catcher arrives. But this one is different, as they discover when the pursuer is injured.

In the lamplight, they saw that one side of the slave-catcher’s skull had been laid bare, most likely by the mare’s hooves. There was no blood, only a slight amount of oily fluid. Instead of pale bone, the gaping wound revealed metal couplings and gears of surpassing delicacy, and bits of glass, some of which shone like embers, blinking on and off.

Yep, a steampunk bounty hunter. Some time later, another group of hunters arrives at Covington’s door, demanding the return of the automaton.

The historical background here is accurate, mutatis mutandis, as is the portrayal of Covington’s Quaker principles. But the notion of the automaton’s soul is unrealistically contrived, and the piece in general is moralistic, with a concluding sermon. The introduction of one particular historical figure is extraneous.

“Solitude” by Naomi Kritzer

Another installment in the serial adventures of teenage Beck Garrison, growing up in Libertarianland. We find Beck, having defied her influential father, kicked out to fend for herself, which is meant to teach her a lesson that Beck doesn’t intend to learn.

This material has reached the point of incomprehensibility for any reader unfamiliar with the previous episodes, and it ends in the sort of cliffhanger that offers no closure in the current situation. There is no beginning here and no ending. The author is also leaning too hard on coincidence. Beck is still an engaging heroine and the basic situation is still of interest, but these installments have ceased any pretence at being individual stories.

“The Assassin” by Albert E Cowdrey

The official Cowdrey is the longest piece in the issue. The setting is a nearish future dystopia in which a Stalinistic dictatorship has taken power in the aftermath of the War. The eponymous assassin was once an idealistic young med student named Andy, who fancied himself a new Sidney Carton. His first attempt to kill the dictator didn’t go well; now he’s trying again, but this time for different, more personal reasons.

Andy’s thoughts were of nothing except killing. He’d finally accepted the harsh demand of Destiny, to leave a woman he’d come to love and a life where he was happy and content, in order to kill a man he’d never met. He could curse the burden, but he couldn’t shift it.

In terms of plot, a “What the hell is going on?” story. We know from near the beginning that things can’t be as they seem, but exactly what is something we have to wait for the story to reveal, in its own time. There’s betrayal and dirty tricks and revenge. But there’s also more to it; rather than a realistic action adventure, what we have is more of a fable, with Andy as the archetype hero we follow on his transformative journey from innocence, down to hell and back in a process of tempering. The scene is set with slogans. Some we see in the text: To Serve All Humanity. Live Free or Die. It is a far, far better thing I do. And others we only hear as echoes: I was only following orders. Power corrupts. Power is the theme of the fable, its corruptive influence. It isn’t one of the author’s typical stories in either setting, tone or narrative voice, but that’s OK

“The Lost Faces” by Sean McMullen

During the reign of Caligula, Marcus Foldor is a slave catcher engaged to retrieve an escaped foreign slave with incredible scientific secrets, including a giant headless fish that can tow barges, controlled by electricity.

“The essence of thunderbolts, according to the Greek slave who writes Father’s letters and tallies his accounts. He thinks the Aegyptians devised these things, but who knows? When applied to living animals, the essence makes their muscles flex.”

Readers will begin this one wondering about the source of Vishesti’s advanced knowledge, whether she is a time traveler, an alien or something else along such SFnal lines. Instead, she turns out be from another line altogether, and not really a fugitive at all but working out a plan of revenge on the Romans who enslaved and corrupted her children.

Unfortunately, it doesn’t make much sense. The giant headless fish, on which the author spends so much of the text, turns out to be mostly irrelevant to the story. Vishesti’s powers are such that we have to wonder how the Romans managed to capture her and her children in the first place, and why she didn’t save them a long time ago, before the Romans worked their corruption. The author also plays coy with the identification of Caligula, who has nothing really to do with the events except that, being Caligula, he must be identified with corruption on general principles. The whole thing is just a mess. I had expected better from this author.

“The Cave” by Sean F Lynch

One day an old, emaciated man comes into the village with a strange tale of being lost in a nearby cave, where he had been prospecting.

The stranger’s weary gaze circled the onlookers. Face flushed, he poured himself more drink and imbibed. Breathing heavily, he said, “For me a month has passed. I marked the days off on me calendar. But I spent twenty days in that hole. When I walked in I was a young man twenty-two years old. And now you see me — I must look seventy if I look a day.”

Some time later, a villager named Aaron and his young son Kaleb enter the cave to explore it and become lost in much the same way.

A strange dark fantasy of warped and twisted time. The excellence is in the strong relationship between the father and his adventurous, imaginative son. There is no use wondering why they took the risk of going into the cave; they had already, perhaps always, been there.

–RECOMMENDED

“Code 666” by Michael Reaves

Jack is an EMT, although his partner Claire is the real medic of the pair. Jack is mostly just the driver. One day the rig is hit on the road and Jack ends up in the hospital with various broken parts. At night, he takes fright from an apparition.

In appearance it did somewhat resemble Frankenstein’s fictional creation: the corpse-like pallor, the emaciated limbs, the long, patchy hair. An oversized gown hung from the skeletal frame like a houserobe on a drying rack. After an eternal moment of blood-freezing terror, Jack realized that this apparition had to be the old man from the neighboring bed, who had evidently grown tired of waiting for an answer.

“Ein krankegeisten!” the revenant hissed at him.

I’m dubious about that German, but it seems to mean the sick ghosts. After which, more weird things start to happen.

A twist on an old classic. The narrative is brisk and well salted with gruesome EMT humor.

“What the Red Oaks Knew” by Elizabeth Bourne and Mark Bourne

Jimi Bone, on the run with a smuggled water lizard in the trunk of his stolen car, meets up with Pink, who makes fetishes. They light off together to hide out in the Ozarks where Pink has unfinished business. The water dragon they stash in a cave, there being some question whether it’s alive or dead. But magic things start to happen.

While they waited for Jimi’s crop to grow the earth turned boggy. Low fields swelled to marshes. Waterfalls sprang jubilant from crags. Wood ducks and greenheads moved to new addresses in previously stubbled meadows.

A wild clash of elemental magics here, neat stuff with vividly-done characters.

“The Boy Who Drank from Lovely Women” by Steven Utley

Evocative title. Monsieur, an 18th century rake, was cursed with immortality by a vengeful Haitian lover. He tells his story.

“You will drink from lovely women and yet always be thirsty. And long after I am dust, you will think of me always with yearning and regret.” And I have. “I will be like knives in your heart, forever.” But there she may have given me too much credit. I may not have had a heart then, though I know now that I have been trying to grow one almost ever since.

We’ve seen the like often from vampires.

“The Long View” by Van Aaron Hughes

The narrator, always in love with the future, moves from Egypt to America to a colony planet, the last made possible by her work on gene modification to slow the metabolism. But she pays a human price. Unfortunately, the story is all recitation and never comes to life.

“The Trouble with Heaven” by Chet Arthur

Charles isn’t happy with his assignment as ambassador to over-entitled Ambrosia, but it turns out to be more interesting than he’d imagined.

“Rulers don’t like to associate with the ruled. They don’t like the way common people look or smell or talk or act. It’s not just fear of thieves and beggars, it’s a kind of visceral loathing for what they used to be themselves before they got lucky. That’s why the French kings built Versailles and the Chinese emperors built the Forbidden City — so they’d never have to see anybody who wasn’t either a servant or a courtier.”

Unoriginal sort of light humor.

“Chet Arthur” is apparently a pseudonym for Albert E Cowdrey, which would make two stories from that author in the issue. I’ve written before of the problems of magazines with a stable of regular authors, but the Cowdrey problem of F&SF is on a level of its own. For more issues than I care to count, there has been at least one Cowdrey story in every table of contents. This is a problem because Cowdrey is just not so good an author to have his own magazine. Not that he is a bad author – by no means. I’ve enjoyed a number of his stories; I like the one in this issue under his byline. But the apparent compulsion to have his work appear at least once in every issue has resulted in the publication of some mediocre stuff, as well as irritation on the part of some readers who think, What? Again?.

This piece is really mediocre stuff. Why the editor should have considered it good enough to earn a second byline in the issue is inexplicable to me. It really raises the question: Is this the best you can come up with? This, in a magazine that, year to year, delivers one of the most superior lineups of fiction in the field?

Interzone #244, Jan-Feb 2013

Some futures bright and dark, some alternaties.

“The Book Seller” by Lavie Tidhar

A Central Station story, which is to say a fragment of the Central Station story that Tidhar has been publishing in dribbles and bits, here and there – an accumulation rather than a serialization, which implies order. In this piece there is a convergence, as many of the previous characters from other segments crowd suddenly and by excessive coincidence crowd into Achimwene’s used bookstore, where he has fallen sort of in love with Carmel the data vampire.

It is, perhaps, the prerogative of every man or woman to imagine, and thus force a shape, a meaning, onto that wild and meandering narrative of their lives, by choosing genre. A princess is rescued by a prince; a vampire stalks a victim in the dark; a student becomes the master. A circle is completed.

Achimwene and Carmel become detectives, investigating the mystery that created her.

If this material were published as a novel, I would like it a great deal more than I do this piecemeal edition. There is a great deal to like; here, there are nice comments on the relationship of fiction and life, which evokes some of the author’s other work. The current piece follows “Strigoi” in IZ 242, which readers of this zine will at least be likely to have seen. Anyone attempting to come to it new will miss too much. And those readers familiar with the previous segments may feel, as I do, that the reappearance of so many characters has become gratuitous, the coincidence greatly overdone.

“Build Guide” by Helen Jackson

Space construction. No one is happy when Murray, the new apprentice, shows up – too young, too inexperienced, too overconfident and determined to prove herself. But Peggy sees the right stuff in her. Problem is, Peggy herself has too much of the wrong stuff.

“Everything’s checked. I wouldn’t let anything past if I wasn’t completely confident.” I was lying, but not much. There’s always the possibility of component failure. My specification changes only increased the chances a little.

Nice verisimilitude in the space setting, and a look at the dirty end of things that always seems to crop up when there’s an opportunity. A smidgen moralistic at the end.

“The Genoa Passage” by George Zebrowski

Nazi hunting in the Apennines time loop. Which is to say, the narrator doesn’t tell us it’s the Apennines but just somewhere on the way to Genoa, a route taken by Nazis escaping capture at the end of the war, a secret of the old guide. “‘The pass,’ he said, ‘splits things up. Not reliably, but often enough to be of interest . . . to some people.'” The guide takes revenge-hunters to pot the Germans caught in time on the trail, over and over again.

A grim and disturbing tale of guilt. The guide assures the narrator that he doesn’t need to bother about identifying his targets. “They’re all guilty.” But the narrator suggests that things aren’t so simple.

“iRobot” by Guy Haley

Ruins in the desert, where two remains lie: one human, one humanoid.

The dust makes the sky brown, the rising sun pale and dirty. Shrouds of dust chase each other through the air, tangling daylight in their umber strands. The sun retaliates, flaring a little brighter, calling shadows from the desert; hard and straight, traces of something beneath the sand.

A nicely-done, light glimpse of futility and entropy. The title is inevitable.

“Sky Leap – Earth Flame” by Jim Hawkins

Facing an apocalyptic threat to their galaxy, humans have devised a complex plan to avert it – perhaps too complex. It is well known that such plans often don’t survive contact with the enemy, in this case reality.

“No human mind can control a ship like yours. We cannot build computers complex enough to do so. Consequently, we started to harness the billion-year work of evolution – we began to build larger and larger biological brains. Most of these have failed. One did not – but an error caused it to die of an infection, stranding its ship and crew ninety-seven light years away.”

The planners have now bred a pair of children and linked them telepathically with a developing superbrain, preparing the triplets for their mission to rescue the original ship and lying to them every step of the way, despite ample evidence that this is a Bad Idea. Contact with reality occurs.

The SFnal premise is audacious and interesting, a lot of neat stuff, although the story frustrates readers as the planners frustrate the children, keeping information from us. The external conflict is simple and clear, once we finally learn what’s going on. The children are capable, precocious and strong-willed. The question is: Will they succeed? Will they save the galaxy, despite the obstacles it throws up? But the core element of the story is the growing relationship among the three young personalities as they mature. This generates internal conflict that promises a lot more interest than the plan’s success. We know that the human twins are capable of rebellion. Will they rebel at the whole project? Will they defy the planners who have lied to them, manipulated them so often? Sex enters the equation, raising the temperature. Yet with all this potentiality, the internal conflict sinks into the external, mostly unrealized. We end up back with the original plan. It’s a good enough plot, but the young protagonists, deprived of true agency for so long, only get their hands on the controls at the end.

“A Flag Still Flies Over Sabor City” by Tracie Welser

In an overly regimented society, young workers rebel in small, permitted ways, steam released so the pressure doesn’t build too high.

There’s a revel in the flow of transgressive words and ideas, illicit conversation where words like “oppression” may as well be expletives. It’s a game to them, a dare, to see how far the others will go, to send hot thrills down one another’s backs and to feel that twist of sensation, like fear but more enticing, in their own stomachs.

A tragedy here, when the transgression goes too far. A reminder to value freedom.

Clarkesworld, February 2013

Not the usual superior stuff this issue, despite the predominance of satire.

“Gravity” by Erzebet Yellowboy

Earth has frozen, but Mair’s elderly mother lives in a past she can’t really remember, when there were flowers growing. The old woman has given everything to support her daughter so she can help restore that world, though she will never see it.

She is not well, but she will not go into suspension. She has told me so. She will not wait for the world to renew. She will not see the sun through the clouds. Mulch, she says. I want to mulch, and then I want you and your daughter to plant flowers on my grave.

It is for her mother’s sake that Mair has joined Earth’s last, most desperate suicide mission.

A pretty standard scenario, trying for sentiment but not achieving it. I can’t help thinking that ice ages and heat ages have always waxed and waned on this planet, and some distant descendants may not be happy with a hotter burning sun, not that this plan is likely to work. But such geophysical considerations don’t seem to inform this piece.

“The Wanderers” by Bonnie Jo Stufflebeam

Sadistic aliens invade Earth, do not find what they expected.

Before you mention it, I will admit that yes, we had come to be your leaders. We had come to slay the ones you called leader before us and to take your whips and reins into our ephemeral hands. This is metaphor, we think. Your red book is unclear on metaphor.

This satire means to subvert the clichés of alien invasion, but fails. The aliens conjecture about what might have happened, but they don’t know and neither do we.

“Vacant Spaces” by Greg Kurzawa

Shepard is the copilot of a salvage tug retrofitted with alien engines that work in ways he doesn’t comprehend. The younger pilot is always ragging on him about being too old for the job. On the current run, things don’t seem to be working right.

In the cockpit, he switched on the external cameras. The array of monitors came alive with a dozen murky viewpoints of local space, all of them the same. Drifting through the exterior floods were thick flakes of what appeared to be snow, but which Shepard knew to be hydrogen. By this, he knew they had indeed traveled distances that he failed to understand.

Worse, Caine the pilot has died during the transit. Even worse, his ghost is still hanging around the tug, complaining even more than he did when he was alive. Shepard’s own ghost isn’t a lot of help. Then things really go wrong.

Here we have full-blown space horror that isn’t scary because the mode is surreal dark comedy. Shepard has no idea what’s going on because the technology involved is alien. But readers know even less, like where the alien technology came from in the first place. Was it salvage? If so, humans are obviously messing with Things We Are Not Meant To Mess With. It’s always possible that somewhere higher up they know what they’re doing, but readers have to reason to suppose any of this is or could be real, so the disasters are all for effect. Shepard is screwed, but that’s his job here.

Waylines Issue 1, January 2013

Debut of a new online zine, featuring stories in print and video media, as well as other nonfiction stuff. I’ll leave the “film” to others and look only at the three short stories. According to the editorial, there is a theme of Decisions, which does fit the selections here. I wish the editors had not decided to print one piece in a tiny white font on black.

“An Echo in the Shell” by Beth Cato

Allison’s grandmother was cursed decades ago to turn into an Asian cockroach. Slowly, this has come to pass.

Long antennae curved from her head and arced a foot in height. Two mandibles protruded from her face and worked at the air. From her shoulders, diaphanous wings clung to her back and stretched the length of her body and through the couch itself. None of that was visible to the human eye, of course. Not yet. Light revealed the strengthening curse, that Grandma’s body had become the husk of a soul-stealing bug.

But the real curse has fallen on her caregivers, and Allison takes control and makes her decision.

This is clearly a metaphor for dementia, which ought to make the tone a tragic one. Yet the cockroach is a direct and explicit reference to Kafka, which gives us absurdity, and at many points appears to be a dark comedy. Should we laugh or cry? It’s not clear.

“Fleep” by Jeremy Sim

Times are hard in the hotel business and guests are scarce, so the last thing Nicholas expects is the alien tourists. He quotes them seven hundred a night as a joke.

The brindlefarb’s eye did not widen. “Fleep.” It lifted one leg and fished a credit card out of a sort of fanny pack that was strapped around its other leg. Its legs were long and flexible, jointless like spaghetti, with three stubby digits at the end.

Complications, of course, ensue.

No question about the tone here. This is humor, subtype comedy of errors. The decisions Nicholas has to make are still crucial for him and his partner.

“The Message between the Worlds” by Grayson Bray Morris

Ankti has spent her life telling herself not to act prematurely, which has caused her to miss every opportunity for happiness, despite her brother constantly telling her, Venture it. At last when it seems to be too late, she gets the point. An awfully contrived, overly prolonged epiphany.

Apex Magazine, February 2013

A Shakespearean issue, on the theme of dying for love. Mostly Hamlet. This is a neat idea.

“The Face of Heaven So Fine” by Kat Howard

Literalizing a passage from Romeo and Juliet. A striking image, quite short. Yet if we’re making these things literal, I have to wonder what kind of person would fall in love with Juliet, knowing you would only and always be second best, a notch on the knife of her love for another.

“Zebulon Vance Sings the Alphabet Songs of Love” by Merrie Haskell

In a future when robotic recreations of past Shakespearean performances are popular, Robot!Ophelia performs an act of rebellion and walks out of the AutoGlobe: I will not die for love tonight.

I have abandoned a show in the midst of Act 4, Scene 7; I have abandoned the six o’clock customer and the paltry Ophelia he wants to wring from me, too.

And Robot!Ophelia learns to live, as it were, for love.

The robotic performer part is a usual SFnal thing, but I admit to thinking I must be missing something when it comes to the figure of Zebulon Vance, wondering why the author chose to put such a persona in this role. Perplexing.

“Mad Hamlet’s Mother” by Patricia C Wrede

From Gertrude’s point of view:

[She] had seen his father’s image indeed—the same cruel intensity, the same fearful menace, the same threat of violence hovering just beneath the surface, ready to explode at the first hint of disagreement. Her son, her sweet, beloved boy, the one good thing she thought she had salvaged from all the long, suffering years of marriage—her son was not her image, but his father’s.

A good interpretative twist.

–RECOMMENDED

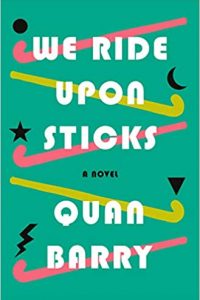

“Dead on Arrival” by Crystal Lynn Hilbert

Eggplant Literary Productions, a very small off-and-on again press, is now producing a series of original novellas, an activity I always like to encourage. This is the first of the year.

After Max bleeds to death all over the apartment, Charlie gets a deep discount on the rent and moves in, despite seeing his ghost around the place. But Max doesn’t want to leave.

She’d come in here, she’d clean. She’d clean him up. She’d take a crowbar to the tiles. Once she started, she bloody well wouldn’t stop. She’d scrub him right out of the damn carpet and tear up the floor there, too. Make them replace the ceiling of the bloke below if that’s what it took, but she’d make him go.

It doesn’t occur to Max [not being the kind of guy to whom deep thoughts tend to occur] that it’s not normal Charlie can see and hear him. Charlie doesn’t take any shit from ghosts. Naturally, Max falls for her. Naturally, complications ensue.

A nice light romantic ghost comedy, nothing really out of the ordinary in that subgenre. Max is your typical dead loser; the more interesting character with the real secret is Charlie, whom we only see through Max’s eyes.

Pingback:real reviews of credit

“I’m dubious about that German, but it seems to mean the sick ghosts.” Alas, no. “Geisteskranker” would be correct for “lunatic”, “madman”; a sick spirit, “ein kranker Geist”, but only in the usual clinical sense. As it is, it’s just badly mangled. I suppose SF authors cannot be bothered.to indulge in strenuous research, like checking an online dictionary or sending off a short query via email…

Thanks for the illumination, Ulrich.

Pingback:Eggplant Literary ProductionsFebruary 17, The Week In Review » Eggplant Literary Productions