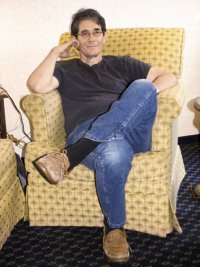

Michael Dirda: Dashing International Man of Mystery and Sophisticated Boulevardier

Michael Dirda was born in Lorain, Ohio. He attended Oberlin College, from which he graduated with Highest Honors in English in 1970, and then taught English in Marseille, France on a Fulbright Scholarship in 1970-71. The following year he went onto graduate school at Cornell University, earning his PhD in comparative literature in 1977 (with concentrations on medieval studies and European romanticism). After working as a technical writer and English professor, he joined the Washington Post in 1978, writing and editing for the Book World section. After 25 years at Book World, he took an early retirement buyout, but has continued to work for the paper as a weekly book columnist and to do other writing as a freelancer. He won a Pulitzer Prize in 1993 for his criticism and has long been a champion of every kind of genre work. Besides his work for the Post, Dirda contributes regularly to The New York Review of Books, currently writes the “Library Without Walls” feature for the online Barnes & Noble Review, and frequently introduces reissues or reprints of older classics.

A prolific and insightful critic, Dirda has published several books: Readings: Essays and Literary Entertainments (2000); An Open Book: Chapters in a Reader’s Life (2003); Bound to Please: Essays on Great Writers and their Books (2005); Book by Book: Notes on Reading and Life (2005); and Classics for Pleasure (2007).

Excerpts from the interview:

“I went off to school, and I was a distinctly dreamy kid. I wasn’t even in the top reading group, though I did love comic books and the Hardy Boys. But when I got to sixth grade, a new kid came to Washington Elementary: blond hair, blue eyes, sort of a Little Lord Fauntleroy. He was the son of the county prosecutor, and he had a genius IQ in math or something. I took one look at him and just hated his guts, and I said to myself, ‘I’m as good as he is. I’ll show them!’ By the end of the year, we were the two top students in the class. The next year, rival school gangs decided to start betting on whether he or I would get better marks on a particular test. Whichever one of us lost would get beat up on the playground. So with apologies to all the usual educational theorists, I started doing well in school first out of envy and later out of fear.”

*

“After I found a cheap paperback of Clifton Fadiman’s The Lifetime Reading Plan, I decided to read all these things you were supposed to get through if you were going to be educated. Of course, I don’t know how much I actually understood of The Magic Mountain when I was 15. But all through this period I was also reading other stuff: My Favorite Science Fiction Story or Great Tales of Terror and the Supernatural, a lot of classic thrillers, adventure, SF, whatever I could find. (Heinlein’s The Door Into Summer made a big impression on me.) My interests were always pretty broad. I would read just about anything, so long as it was either exciting or written in a way that appealed to me.”

*

“I came to the Washington Post, mainly because my girlfriend (later my wife) had been working in DC. After some time as a technical writer for a computer company, I started reviewing for Book World, and then was hired as an assistant editor. In the late ’70s Book World ran an occasional SF column by A.J. Budrys, maybe three or four times a year, but when I’d been there only a short time A.J. left to be a columnist for the Chicago Sun Times. Well, the Post had monthly columns devoted to mysteries and children’s books, and I convinced my colleagues that we should add a monthly fantasy and science fiction feature as well. They said, ‘OK, you’re in charge.’

“During my college and graduate school years I hadn’t read any SF, just all this serious, canonical stuff. So I wrote to the only SF writer I knew personally, Joanna Russ. Joanna used to come up to Ithaca from Binghamton, where she was then teaching, and we would sometimes meet at parties. I told her that I had this chance to do something with fantasy and science fiction, starting in six months. What books should I read? She sent me a list of major novels, and pointed me to works of criticism like Damon Knight’s In Search of Wonder and other things I had missed as a teenager. I remember being on a bus in Wisconsin, as happy as I’ve ever been, reading The Stars My Destination for the first time.”

*

“I’ve also always tried to review at least one major book in the field each fall and spring, usually those that publishers think of as ‘breakout books.’ More often than not though, I seem — regretfully — to have given many of them mixed reviews. I admired but had cavils or, in some instances, serious reservations about Neil Gaiman’s American Gods, Susanna Clarke’s Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell, Elizabeth Kostova’s The Historian, Neal Stephenson’s Anathem. Anathem, for instance, won the Locus Award, and a lot of people obviously love the book, but it didn’t work for me. I found it too long, too slow-moving, too heavy.

“Of course, I could be dead wrong about Stephenson’s novel. The books we can’t make sense of, that knock us off-kilter, that we don’t accept readily, will often be the books that matter most to the next generation. In fact, that’s generally the sign of a really important book: it doesn’t fit into our received expectations, it bothers us, it ‘doesn’t work.’ Sometimes an ambitious failure is more worth having than a successful little novel that is perfectly well done.”

*

“I loved every sort of book as a kid. Since I became a newspaper critic and reviewer, I still get a lot of pleasure from what I read, but I don’t read for pleasure anymore. Haven’t done so for decades. I read in a different way — more analytically and usually for money. But the pure rush of pleasure, what we talk about when we say in SF that ‘The golden age is 14,’ is hard to come by later in life. Certainly it is for me. Always at the back of my mind is, ‘Maybe I’ll make use of this.’

“Good books, it has always struck me, can be found in every genre. That’s the premise behind my most recent collection of essays, Classics for Pleasure. I write there about every sort of classic: Sappho’s love poetry and M.R. James’s ghost stories, John Webster’s dramas and Georgette Heyer’s regency romances. These are all works that, in some way, have shaped our imaginations. The overemphasis on genre boundaries really is shortsighted. But I do think things are breaking down now. About 30 years ago, I published a piece in The Nation called ‘The Genre Ghetto’, and there maintained that the divisions between branches of literature were often artificial and were usually just marketing tools. I sensed that in the coming generation, more and more serious writers would come out of fields like fantasy and crime fiction. These writers would adapt genre tropes and ideas and themes to a so-called mainstream literature.”

This review and more like it in the December 2009 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.