John Langan reviews Christopher Buehlman

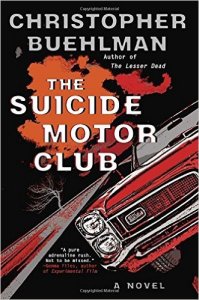

The Suicide Motor Club, Christopher Buehlman (Berkley 978-1101988732, $26.00, 368pp, hc) June 2016.

The Suicide Motor Club, the new novel from Christopher Buehlman, is a lean, mean, souped-up, eight cylinder, four-speed race car of a book. It begins at high speed, with Judith Lamb, the protagonist, in a car with her husband and five-year-old son. The year is 1967, and the Lamb family is driving east through New Mexico, on their way home from a wild west-themed vacation. Without warning, the family is flanked by a fast, black car, one of whose passengers reaches between the moving vehicles to snatch their son from the back seat. As Judith fights a losing battle to hold onto her son, she sees that the men and woman in the car beside her are deathly pale, their mouths bristling with sharp teeth. Once her son is in the black car, it pulls away, leaving a second car which has approached from behind to nudge the Lambs’s car into a rolling wreck. The accident mortally injures Judith’s husband, and though she escapes serious hurt herself, she is left widowed and bereft of her son, no trace of whom can be found. Eventually, she decides to seek solace by taking holy orders at a convent in Ohio.

The Suicide Motor Club, the new novel from Christopher Buehlman, is a lean, mean, souped-up, eight cylinder, four-speed race car of a book. It begins at high speed, with Judith Lamb, the protagonist, in a car with her husband and five-year-old son. The year is 1967, and the Lamb family is driving east through New Mexico, on their way home from a wild west-themed vacation. Without warning, the family is flanked by a fast, black car, one of whose passengers reaches between the moving vehicles to snatch their son from the back seat. As Judith fights a losing battle to hold onto her son, she sees that the men and woman in the car beside her are deathly pale, their mouths bristling with sharp teeth. Once her son is in the black car, it pulls away, leaving a second car which has approached from behind to nudge the Lambs’s car into a rolling wreck. The accident mortally injures Judith’s husband, and though she escapes serious hurt herself, she is left widowed and bereft of her son, no trace of whom can be found. Eventually, she decides to seek solace by taking holy orders at a convent in Ohio.

Judith’s story at a temporary pause, the narrative now shifts point of view to a series of women and men who have their own brief, fatal encounters with the men and woman who destroyed Judith’s family. As her vision of them suggested, they are vampires. These are the monsters of tradition: predatory, malevolent, difficult to kill. They travel the highways and byways of the country by night, never stopping in one place for too long, lest they drawn attention to themselves. Most of the people the vampires meet immediately succumb to their glamour, allowing the creatures to separate their intended victims from any friends or family, and also to plant in the memories of those left behind a different version of events, one from which the vampires are absent. To further cover their tracks, the vampires stage their murders to resemble suicides, which, combined with the fast cars that are their preferred mode of travel, gives the book its title.

All of this Judith learns not long after she has entered the convent, when she is visited by a man who identifies himself as a member of a group called the Bereaved. He has sought her out to tell her that her family was taken from her by vampires and to ask her for her help in destroying them. She agrees on the spot, and in short order has departed the convent with the man, on her way to join a small group of men who have dedicated themselves to the defeat of the creatures who killed their own loved ones.

From here, the narrative hurtles headlong towards the confrontation between Judith and her fellows in the Bereaved and the Suicide Motor Club. Writing a prose that is simultaneously stripped down and lyrical, Buehlman guides the story towards a thrilling, fiery climax. In many ways, this novel is built to the model of the summer blockbuster: a plot based in a conflict between good and evil, shifts among multiple points of view, characters who exhibit above-average competency in their respective (and necessary) skills, dramatic and decisive action. But Buehlman invests this familiar structure with depth and resonance, creating compelling characters whose fates matter to the reader. This is the case with Jude, but also with Luther Nixon, the leader of the vampires, who is given a trio of monologues that take him beyond cardboard cutout to a villain of some texture and complexity. In addition, Buehlman uses the novel’s late-sixties setting as more than window dressing (not to mention a convenient way to avoid the narrative challenges posed by the age of cellphones and the Internet). His vampires insert themselves into the cultural discourses of the time, using them as camouflage for their intentions. Not to mention the fact that his choice of Luther Nixon’s last name is hardly innocent.

There’s a consonance between this novel and Buehlman’s previous book, the excellent The Lesser Dead. Both books concern vampires who are imagined in pretty much the same way; indeed, there’s a brief reference to the earlier novel in this one. (Interestingly, both novels present vampires who are members of the lower class.) They’re a welcome rejoinder to the assorted Dogme 95-style prohibitions against the use of such traditional horror figures. Indeed, the only substantial complaint about The Suicide Motor Club that can be made is that it ends on a cliff-hanger, the first of what appears to be at least a two-book series. No matter: there is plenty here to enjoy in the meantime.