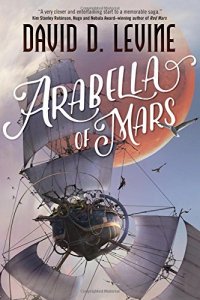

Paul Di Filippo reviews David D. Levine

Arabella of Mars, by David D. Levine (Tor 978-0-7653-8281-8, $25.99, 352pp, hardcover) July 2016

This seems to be a “steam engine time” kind of period in publishing, when writers who have focused exclusively on short fiction for many years now step forth with their long-anticipated debut novels. (There are always plenty of debut novels, of course, in any given year, but not many of their authors nowadays have a decade or more of short-story production behind them, having instead vaulted straight to long form.) Ken Liu brought us The Grace of Kings. Yoon Ha Lee issued Ninefox Gambit. And now comes David Levine’s Arabella of Mars, ushering him into hardcovers some twenty years after his first story appeared (“The Worldcon that Wasn’t”) and a longish time after his 2005 Hugo win for “Tk’tk’tk.”

This seems to be a “steam engine time” kind of period in publishing, when writers who have focused exclusively on short fiction for many years now step forth with their long-anticipated debut novels. (There are always plenty of debut novels, of course, in any given year, but not many of their authors nowadays have a decade or more of short-story production behind them, having instead vaulted straight to long form.) Ken Liu brought us The Grace of Kings. Yoon Ha Lee issued Ninefox Gambit. And now comes David Levine’s Arabella of Mars, ushering him into hardcovers some twenty years after his first story appeared (“The Worldcon that Wasn’t”) and a longish time after his 2005 Hugo win for “Tk’tk’tk.”

Arabella proves to be well worth the wait. It is a straight-up tale of incredible yet believable adventures fit to have flowed from the quill of Robert Louis Stevenson. It is old-school Planet Stories SF without snark, smarm or apologies. At the same time it is utterly state-of-the-art, 21st-century in its sensibilities and technics. It’s an intriguing counterfactual slightly reminiscent of Novik’s Temeraire series. It’s nuts-and-bolts gadgetry SF that John Campbell would have proudly adopted. It has gravitas and humor, romance and battle, sacrifice and victory in large measures. In short, I can’t see this book—and its intended successors, since it’s labeled Volume 1—as being anything but a huge triumph.

Here’s the conceptual background. The duration of our narrative is a mere several months spanning the years 1812 and 1813, but on a continuum divergent from ours to a large degree. In this universe, a breathable aether or atmosphere, with winds, permeates the interplanetary distances, enabling unpressurized ships to sail from planet to planet, once they launch themselves from terra firma. (And who was the first man to make the voyage from Earth to the Red Planet? None other than Captain Kidd!) Mars and Venus are both habitable by humans, and are basically the kinds of world described in those recent anthologies by Dozois and Martin, Old Mars and Old Venus. Mars boasts natives—carapaced, craboidal bipeds—and we can assume Venus has her aliens as well, though that planet is outside this installment’s purview. Mars is dry and sandy, Venus swampy.

The Ashby plantation on Mars is a rich estate providing a special kind of tree used for ship-building, where our heroine dwells with her older brother Michael and two younger sisters. Born on Mars, seventeen-year-old Arabella loves the place. Her mother, however, does not, and succeeds in relocating herself and the reluctant girls back to Earth, leaving the menfolk behind.

Arabella is miserable on the strange “homeworld.” And when her adult cousin Simon conceives of a plan to voyage to Mars to wrest the plantation deceitfully away from brother Michael, Arabella’s only course is clear. She must follow Simon and prevent the usurpation. This strategy involves disguising herself as male; enlisting on a commercial vessel under the redoubtable Captain Singh and his cybernetic (and sentient?) navigator, Aadim; and facing hardships galore, including manning the motivating pedals of the ship; dealing with surly rival crew members, pirates, and mutineers; and laboring for days of emergency charcoal-burning on a remote forested asteroid.

But if the journey as a sailor to Mars is difficult and taxing, what follows upon landing is pure heartbreak and savagery. I shall not spoil your thrills by detailing the events in advance of your reading.

Levine’s breakdown of his story into various organically interflowing sections is capably designed to maximize the engagement of the reader and the maturation of Arabella. First comes the brief opener on Mars, which tells us a lot about the planet, this peculiar universe and the Ashby family. The few chapters on Earth set the MacGuffin of Arabella chasing Simon in motion, the whole engine of the plot. The huge majority of the book is Arabella’s service on Captain Singh’s ship during the Earth-Mars transit, which shows us the intricate mechanics of celestial travel, all vividly described; Arabella’s trial by fire and the refinement of her natural strengths; and her growing emotional attachment to Singh, along with many scary and amusing interactions among the crew. Finally, the climactic section on Mars reveals Arabella’s new capacities, ties up the family matters, and positions a springboard to future installments.

Arabella is onstage on every page, and a charming creation she is. No superwoman nor suffragette, she nevertheless by simple competence, bravery, talent and spunk proves herself equal to any of the male characters and superior to several. Her trepidations, fears and mistakes are given fair weight as well, rendering her sympathetically fallible. The rest of the cast achieves a nice roundedness as well. Singh reminded me of another Asian captain from fantastika—Verne’s Nemo, though less dour and doomed.

What is really miraculous about this book is the way Levine balances between deep cognitive estrangement and pure surface storytelling. Here’s what I mean. Suppose this same story had been told by, say, Ian MacLeod or John Crowley. The balance would have tipped, I think, towards a density of effects and interiority, producing a book similar to The Light Ages or Engine Summer—both wonderful, excellent books, but involuted. Now suppose Edgar Rice Burroughs—an obvious influence and ancestor here—had written Arabella of Mars. Well, you know how that volume would have read, all breathless action but somewhat shallow and pulpy. But instead of either of those two extremes, Levine has produced a book that combines the best of both modes.

Part of this derives from his very deft and poetically calculated language. He has found a graceful style of prose that achieves a certain gravitas without being Henry Fielding. It is not full-bore 1812 syntax and rhetoric, but neither is it anachronistically 21st-century speak. Arabella’s attitudes and language artfully reflect the mindset and education of a girl of the Napoleonic era. The voice of the omniscient narrator continues in this semi-formal, semi-familiar vein, conducive to easy, yet challenging reading. The reader is quickly absorbed into the new world, her senses sharpened for the twisty bits while relishing the homey parts.

Feisty young ladies from Mars used to be represented by ERB’s Dejah Thoris and Heinlein’s Podkayne (and to a lesser degree by Al Sarrantonio’s criminally neglected Haydn of Mars). Now to this illustrious roster we can add Arabella, who, if her later adventures adhere to this high standard, might outshine them all.