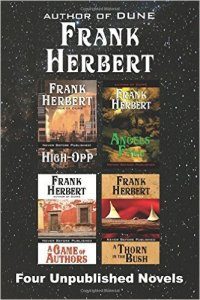

Paul Di Filippo reviews Frank Herbert

Four Unpublished Novels: High-Opp, Angel’s Fall, A Game of Authors, A Thorn in the Bush, by Frank Herbert (WordFire 978-1614753391, $19.99, 570, trade paperback) February 2016

Out of all the major writers of his generation, Frank Herbert (1920-1986) seems most in danger of becoming remembered solely for one novel—or rather, the series which that novel launched. Mention his name today, to fans old and new alike, some thirty years after his death (my lord, how did three decades zip by so fast!), and the universal response is likely to be, “Yes, of course, the author of Dune!” Overlooked or forgotten are all the other fine books of his career.

Out of all the major writers of his generation, Frank Herbert (1920-1986) seems most in danger of becoming remembered solely for one novel—or rather, the series which that novel launched. Mention his name today, to fans old and new alike, some thirty years after his death (my lord, how did three decades zip by so fast!), and the universal response is likely to be, “Yes, of course, the author of Dune!” Overlooked or forgotten are all the other fine books of his career.

This one-trick-pony status does not adhere, I think, to many other Grandmasters (although of course, technically speaking, Herbert never was awarded that specific prize from SFWA, although a strong case could be made that he deserved it). Heinlein’s reputation currently encompasses several well-regarded masterpieces, as do the legacies of Clarke, Asimov, Bradbury, Pohl, Vance, van Vogt, and other deceased members on that honor roll. Maybe Clifford Simak is the fellow who is somewhat in an analogous position, with City being almost his exclusive milestone in the eyes of most people.

Now, it’s wonderful that posterity remembers anything about any writer thirty years after his death, even if they recall only a single book. Most writers fade into total obscurity soon after they are no longer around to promote themselves. But perhaps it’s time for a more nuanced view of Frank Herbert than just “that guy who invented sandworms.”

Certainly Frank Herbert’s son Brian has done much to promote his father’s varied oeuvre. And second in line as a booster is Kevin J. Anderson, who has famously and ably continued the Dune franchise with prequels. With the formation by Anderson of his own small press, WordFire, the living author has done even more to honor his dead colleague. He has brought several of Frank Herbert’s titles back into print. Moreover, he has found and published four trunk novels from the elder statesman. Originally issued as singleton volumes, they are now available in an omnibus at a bargain price. This is a major moment for both scholars and pure readers. (Also on tap is a volume of Unpublished Stories, not quite ready for sale as of this writing.)

As Anderson reveals in his introduction, these four books were composed after the success of Herbert’s first novel, The Dragon in the Sea (1956). They are finished product, deemed fully polished by Herbert at the time. But unable to place any of them, even with the help of agents, he moved ahead to Dune, serialized beginning in 1963, and the rest is history, with these novels languishing. Consequently, these books reflect the vintage era of their composition.

High-Opp is almost the perfect Galaxy novel of The Space Merchants variety, so much so that it seems almost a pastiche or parody crafted to hit every plot point, and redeemed mainly by Herbert’s insights into power dynamics and the psychological twists and turns of the human soul under pressure.

Once again, society and the world have been rigidified inequitably along monomaniacal lines. Polling and a new science that reduces the randomness of predictions all led to a tyranny of the Majority, aided by computers and other gadgets. (“Gallup” and “Roper” are exclamatory deities.) High-Opp people are the elite, while the Low-Opp hoi polloi suffer. But some of the elite have recognized that the system is rotten and must fall, so they are subverting it from within. These schemers engage our hero, Daniel Movius (a name indicative of some “Prime Mover” perhaps?) as their stalking horse, willing to sacrifice him to provoke rebellion. But he proves uniquely adapted to his role, and with the capacities of a van Vogtian hyper-brain and a sternness of character, he surges to a paramount victory.

The whole arc of the book takes place over just a few months, and Herbert is unrelenting in his pacing. The action scenes are staged with verve, the dialogue is realistic and gripping, and there’s even some super-science rigmarole with spy rays and the like. The cultural adaptations to this stratified social structure are convincingly extrapolated. The tensions between Movius and his wife Grace partake of those Phildickian battle-of-the-sexes rituals emblematic of 1950s America. And there’s a The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit ambiance to the Machiavellian struggles. But despite—or perhaps because of—this colorful, not always coherent mélange, the novel is vastly entertaining and unputdownable.

The 1950s saw a fascination with noirish jungle adventures, in both movie and book form, starting with 1951’s The African Queen. Take one white-man tough guy, seedy and amoral, perhaps “gone native,” add in some female love interest, nasty bad guys, savage tribes-people, a treasure, physical challenges of the wilderness, and you had the ingredients for an infinite number of tales. Secret of the Incas from 1954, arguably the model for Indiana Jones’s later adventures, is something of an apex in the genre. In Angels’ Fall, Herbert gives the mode his best efforts, and assembles a riveting novel that should have been a primo Gold Medal Paperback Original at the time.

Jeb Logan runs a small two-airplane cargo-hauling firm in Ecuador. Into his life unpromisingly comes client Monti Bannon and her son David, on the trail of her husband, who’s gone missing in the jungle. Convinced against his own instincts to ferry her out, Jeb and his plane and passengers go down on a river. They pick up Bannon’s creepy partner, Gettler, and now the four have to take the plane downriver back to civilization, facing headhunters, wild beasts—and the brutal domination of the vicious Gettler. It’s a harrowing, thrilling journey.

Bouncing amongst the consciousness of all his characters, as he did in Dune, Herbert evokes sympathy for everyone. And bits and pieces of these inner narratives foreshadow his later concerns: “Fear is the penalty of consciousness…The images within my mind are part of me, he told himself. I don’t need to fear them. They’re the past.” Holy Bene Gesserit, all you House Atreides followers!

Herbert concocts an intriguing premise for A Game of Authors, and then inhabits it in his best John D. MacDonald suit. He takes the famous disappearance of Ambrose Bierce into Mexico and conflates it with Cold War espionage. In the case of this novel, the vanished author is one Antone Luac, who absconded decades ago with Anita Peabody, the wife of another man. Getting a clue about Luac’s continued presence in the little town of Ciudad Brockman, Mexico, investigative freelance journalist Hal Garson heads down for the scoop of a lifetime. But amidst a cast of colorful locals, including the hulking and dangerous Choco Medina, Garson soon finds his life in danger, and learns that Luac is involved—or at the mercy of—some ruthless conspirators. Luac’s beautiful daughter Anita, named after her dead mother, spices the pot and plot.

Herbert’s amusing tough-guy dialogue is counterbalanced by his portrait of Luac, which captures Bierce’s famous misanthropy and epigrammatic brilliance. The action and suspense are reasonably fierce. The depiction of Garson walks a fine and convincing line between pigheaded self-interest and nobility. All in all, one could easily envision a film version of this with Robert Mitchum in the lead, like some lesser-rate Out of the Past.

Last and least consequential, but still enjoyable, comes A Thorn in the Bush, another Mexican adventure (inspired by Herbert’s travels to that country), a kind of cat-and-mouse game between the mysterious Mrs. Ross, expatriate, and a visiting painter who is stalking her. Oddly enough, it has almost a Eudora Welty vibe.

Besides providing some true and undiminished reading pleasure, these four forgotten novels shine a probing and revelatory light on the career of one of the fields geniuses, filling in missing pieces of a career cut short too soon.