Father Doesn’t Know Best: A Review of After Earth

by Gary Westfahl

by Gary Westfahl

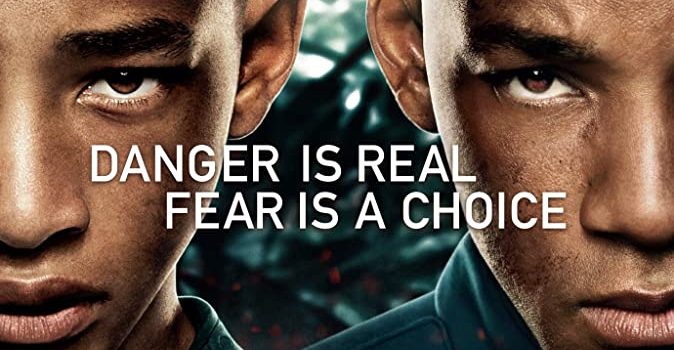

Based on their track records, one cannot approach a science fiction film starring Will Smith and directed by M. Night Shyamalan with extreme optimism. Despite occasional ventures into more subdued projects, Smith has specialized in mindless, action-packed spectacles that, like roller coaster rides, provide immediate excitement but nothing worth remembering. And Shyamalan doggedly crafts puerile contrivances masquerading as thinking man’s cinema, infused with purported profundities recalling the sentiments found on Hallmark Cards. If reviewers now tend to approach their films with knives drawn, one might say, that is a fate they richly deserve.

Yet critics must also offer honest assessments of each new film they watch, and After Earth is, strangely enough, not as awful as one might expect; it may be mediocre, but it is not execrable, perhaps because the two massive egos dominating the project managed to restrain each man’s distinctive excesses. Developing a story about a father and son stranded on a future Earth inhabited only by vicious creatures, Smith might have been drawn to crowd-pleasing devices like the implausible discovery of a small band of human survivors led by a beautiful young woman, who could first school young Kitai Raige (Jaden Smith) in the art of survival and later function as a threatened heroine to be rescued from the latest monster; but Shyamalan, determined to appear mature and thoughtful, would reject such nonsense as a diversion from his inspirational saga of a young man learning to master his own destiny. And as Shyamalan worked on his revisions of Gary Whitta’s screenplay, adding platitude after platitude, Smith would start crossing them out, pointing out to the director that adventure films are often enhanced by laconic heroes who carry out their duties while maintaining a stoic silence. Still, while this creative tension may have had beneficial results, it may also be why the film is, by contemporary standards, unusually short (99 minutes): large amounts of material may have been omitted from the final print. (Shyamalan: “We have to take this out; it’s too mindless.” Smith: “We have to take this out; it’s too puerile.”)

As these imaginings suggest, After Earth is the sort of film that inspires viewers to ponder the drama of how the film was made, which was probably more involving than the drama unfolding on the screen; and while critics might envision the film as an ongoing argument between Smith and Shyamalan, others will probably focus on the film as an explicit mechanism to effect a Hollywood changing of the guard. Smith, approaching the age of fifty, recognizes that his days as an action hero are numbered, and that he will inevitably have to begin playing the avuncular fathers and grouchy bosses of action heroes instead; so, he crafts a story designed to pass the torch on to a new generation, namely, his son Jaden. Smith would play a mature, experienced general, Cypher Raige, who tellingly informs his wife Faia (Sophie Okonedo) that he will soon be “announcing his retirement.” Then, after being injured in a spaceship crash, he is forced to dispatch his son Kitai to carry out a dangerous mission while he provides some long-distance mentoring. With Jaden’s mother Jada Pinkett Smith and uncle Caleeb Pinkett also on board as producers in this obvious effort to launch Jaden’s career, the film may qualify as the world’s most expensive fifteenth birthday present ($130 million). But will the planned transition be successful? Smith, surely, will have no trouble adjusting to older roles, but whether Jaden will be able to fill his father’s shoes is more questionable; his character’s name, Kitai, is Japanese for “hope,” possibly reflecting his ambitions, but one does not always get what one hopes for. It appears that Shyamalan deliberately filmed in sequence anticipating that his star’s improving acting skills, under the tutelage of his credited acting coach, Aaron Speiser, would mirror the developing competence of his character; and in fact, Jaden’s acting in the film does progress – from embarrassing to adequate. It remains a performance, though, that will not impress any film producers whose last names are not Smith.

The weakness of its star at least should have the effect of defusing one brewing controversy, that the film is little more than a propaganda piece for Scientology, the controversial religion espoused by Smith and other celebrities like Tom Cruise, who starred in a recent film with a similar plot, Oblivion (review here). I must leave it to persons more familiar with Scientology to determine whether Shyamalan’s grandiose pontifications, or the film’s theme of overcoming fear to achieve one’s full potential, are closely related to its doctrines. However, even if there was some intent to promote Scientology in the film, it must be regarded as a hopelessly ineffectual effort, since absolutely no one is going to walk out of the theatre with an overwhelming desire to find a religion that will transform them into a person as wonderful as Jaden Smith.

If there is anything genuine moving about this film, it is something that may have been unintentional, namely, the way that After Earth illustrates everything that is wrong about modern parenting: it is both too distant and too overbearing. That is, encouraged to pursue their own interests above everything else, many parents devote almost all of their time to their jobs and their hobbies, never developing a genuine relationship with their children. Yet thanks to modern technology like cell phones, computers, and GPS systems, they are also able to constantly monitor and control their children’s activities, and they often choose to do so. Jaden’s experiences with his father epitomize these problems. Many cultures, as a rite of passage, send young men out into the wilderness to survive on their own and thus demonstrate that they are prepared for adulthood, and Smith’s story is clearly intended to recall such traditions, as the father is obliged to send his young son, the only other survivor of the crash, on a lonely mission to retrieve a distant signaling device. Yet this is a vision quest with a distinctly modern twist: Smith’s Cypher has previously been a cold and perpetually absent parent (as indicated by his name, Cypher, meaning “puzzle”), yet after giving his son some instructions and sending him on his way, he also utilizes futuristic technology to observe his every move and regularly tells him exactly what to do next. When an accident damages these communication devices, one might imagine that Jaden would welcome the freedom to search for the film’s McGuffin in his own way, yet as soon as he can, he eagerly reestablishes contact with his father, who fights to remain conscious despite his injuries so that he can issue a few more commands to his son. So are revealed the incongruous dynamics of the modern family: helicopter parents, who don’t really know their children, feel compelled to be the masters of their lives; the children, who don’t really know their helicopter parents, despise them, based on what little they do know; yet they also feel utterly lost without them, and whenever they are absent, they desperately miss them.

(In another minor respect, Jaden further reflects the plight of contemporary children: since we have filled their worlds with pollutants and contaminants, more young people than ever suffer from asthma, making them dependent upon inhalers; in the film, since Earth’s atmosphere has grown more difficult to breath, Jaden must periodically pull out and inhale a soothing substance from small discs that resemble smaller versions of today’s ubiquitous Advair inhalers.)

Having been trained in the art of writing science fiction by the likes of Roland Emmerich and Barry Sonnenfeld, Smith provides his film with a story that few devotees of the genre can admire. The initial crisis occurs after Smith identifies, by touching the side of his spaceship, a “graviton disturbance”; this quickly provokes an “asteroid storm” that damages the vehicle and forces it to crash-land on Earth. Unsurprisingly, the film’s credits do not identify a “science advisor” who assisted Smith in devising these gobbledygook explanations. While we are never told how they managed to change Earth’s atmosphere and climate in one thousand years, the film’s evil aliens are said to have rendered Earth uninhabitable by inducing rapid evolution that turned every creature on Earth into a killing machine, apparently making the planet into a version of Harry Harrison’s Deathworld, so lethal as to require all humans to emigrate to another world, Nova Prime. Yet Jaden is able to spend hours walking through deserted landscapes without being disturbed, and he even encounters one friendly animal, a large mother bird who adopts him as a surrogate son (and, following the pattern of the helicopter parent, keeps flying above him, observing his progress). Jaden’s mission is to retrieve and turn on a rescue beacon to bring assistance, but an advanced civilization would undoubtedly develop some sort of automatic signaling device for spaceships that fall to pieces, and they would also create one that is not easily blocked by an “ionic layer” in the atmosphere, dramatically requiring Jaden to climb up a volcano. In sum, Shyamalan may have impelled Smith to avoid major idiocies, but any number of minor idiocies proved necessary to keep the plot in motion.

I suppose something should be said about the film’s setting, an Earth reclaimed by nature one thousand years after humans evacuated the planet in response to an alien invasion. Unlike other films about a devastated future Earth, including Oblivion, the heroes never encounter the ruins of iconic structures like the Statue of Liberty or the Empire State Building, which exemplifies one of Shyamalan’s peculiar strengths: he is drawn to the stupid, but he avoids the obvious. instead, the only sign of human history comes when Jaden enters a cave and sees some ancient cave paintings, also suggesting that his spaceship landed somewhere in present-day Europe (though the filming actually occurred in Costa Rica, Utah, and Northern California). Shyamalan may have wished to indicate just how fleeting humanity’s grasp on the planet might be, or to argue that it is only by returning to the beleaguered, simple lifestyle of their ancient ancestors that people can reconnect with their true identities (though Jaden and his father also seem completely dependent on their thirtieth-century technology to survive). Further, since all of Earth’s animals except one have now turned against humans, violently attacking Jaden at every opportunity, After Earth qualifies as another film about the revenge of nature, a theme that emerged, more risibly, in Shyamalan’s earlier disaster, The Happening (2008). Perhaps, though, the true inspiration for this vision of Earth’s future was the documentary television series Life After People (2009-2011), which speculated about what would happen if humanity suddenly vanished, and offered the subliminal argument that all of the animals and plants would be much better off if we left.

A critical essay I do not wish to write would explore the reasons why so many contemporary films envision a future that represents a return to the past, either in human history or human prehistory; only rarely does one glimpse a future Earth that is both technologically advanced and benevolently governed. (The only recent instance that comes to mind is Star Trek into Darkness [review here]). But After Earth returns to the past in an especially provocative fashion by presenting what is effectively a man’s world. The major women in the story, Cypher’s wife and daughter, are only briefly glimpsed in flashbacks, and while there are a few scattered females in the background, the people on the spaceship with real authority are uniformly male. Indeed, it says a lot about this film to note that its most well-developed female character is a bird. Granted, most contemporary action films continue to focus mostly on male heroes, but filmmakers are usually careful to feature a few prominent, powerful women as well; perhaps Shyamalan, focused on other priorities, simply forgot about this standard requirement. But this may also represent another message embedded in the story: it’s all right to have women in control during times of peace, but when a real danger emerges, like homicidal aliens, we need the men to take over. After all, Cypher may have named his daughter Senshi (Zoë Isabella Kravitz), which is Japanese for “warrior,” but she utterly failed to defeat an attacking alien, while her younger brother ultimately succeeded. (Pondering the paucity of assertive female characters in Shyamalan’s films who are not portrayed by Bryce Dallas Howard, I discern the outlines of another critical essay I do not wish to write, “Sexism in the Films of M. Night Shyamalan.”)

To remind everyone of how smart he is, Shyamalan is also impelled to work a lofty literary reference into the story, so we learn that Herman Melville’s Moby Dick (1851) is Cypher’s favorite book, and in a flashback, his deceased daughter even displays a copy of the book. And yes, there is a large, dangerous creature menacing our wandering protagonist, since the crashed spaceship also contained a lethal alien, the Ursa, who escaped to carry on with its proclivity for seeking out and killing any humans who emit pheromones conveying their fear. Yet it is hard to discern any meaningful connection between the novel and film, since no one is vengefully obsessed with tracking down and killing the alien; rather, they are obsessed with avoiding the alien at all costs. More broadly, while this is not the occasion for an extended discussion of Melville’s novel, one can briefly note that none of its themes really resonate with the story of an adolescent who is struggling to overcome his fears. If Shyamalan had wanted to engage in a dialogue with a great literary work, he might have more fruitfully focused on the other masterpiece of nineteenth-century American literature, Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn (1884), the story of a boy who significantly matures during a long adventure that even involves, like Jaden’s journey, some traveling down a river on a makeshift raft. Unfortunately, exploring such a connection to Twain would have required the film to display what Shyamalan’s films never display, namely, a sense of humor.

Overall, considering a film that is sporadically entertaining but generally disappointing, I am obliged to emend a previous argument. In other reviews, I have decried the play-it-safe mentality of contemporary films, the desperate desire to incorporate the input of innumerable people to ensure box-office success that so often results in dull, mechanical exercises; I have called for filmmakers to resist Hollywood groupthink, make their own independent decisions, and craft original, idiosyncratic films that dare to break the rules. However, in the person of M. Night Shyamalan, we observe a filmmaker who has fought to achieve precisely that sort of freedom, yet he consistently abuses that freedom to produce really, really dumb films. Perhaps, like other successful writers and directors, Shyamalan needs a regular partner who might prevent him from so often shooting himself in the foot; and if Will Smith is not the ideal choice, there are other powerful creators around who might productively prod this talented but error-prone director to make films that could garner more positive reviews.

Jadfen Smith requested emancipation from his parents a few weeks before the film’s opening, giving this observer the idea that the kid doesn’t want to be an actor.

You might want to do just a little bit more research on that, Robert.

Smith: “We have to take this out; it’s too puerile.”

Yeah, I can just see Will saying that. Uh huh.