Liz Bourke Reviews The Principle of Moments by Esmie Jikiemi-Pearson

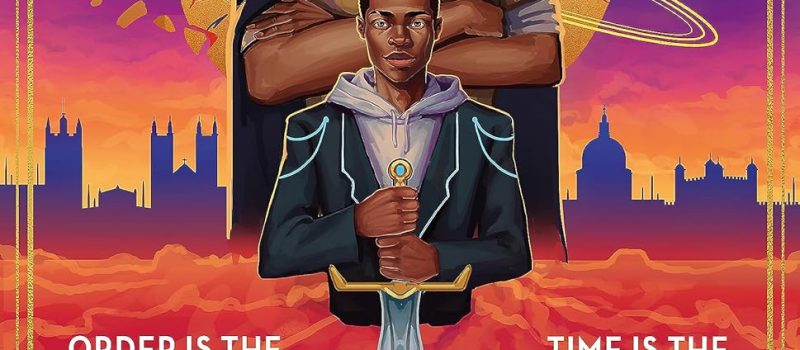

The Principle of Moments, Esmie Jikiemi-Pearson (Gollancz 978-1-47323-419-2, £18.99, 520pp, hc.) January 2024.

The Principle of Moments, Esmie Jikiemi-Pearson (Gollancz 978-1-47323-419-2, £18.99, 520pp, hc.) January 2024.

Esmie Jikiemi-Pearson’s The Principle of Moments, the debut original novel from the first winner of the UK’s Future Worlds Prize for Fantasy & Science Fiction Writers of Colour (in 2020), feels like an answer to the question of: What happens if you cross Star Wars with Doctor Who? And then make it queer (queerer in Doctor Who’s case), Black, and fundamentally disinterested in making excuses for the violence of empire?

In 1812 London, young time-traveller Obi Amadi has finally come back to the prince who loves him after searching for (and failing to find) his father across time and space. Obi suffers from a time-travelling sickness: He can jump across time, but every time he does, he loses a part of himself. (A tooth. A finger. An eye. A rib. An entire limb.) Obi wants to stay, this time, though he can’t shake the belief that everyone who loves him will eventually abandon him. His insecurities aren’t helped by the fact that his lover is in line for a crown, and will have to marry.

Prince George is a figure that doesn’t exist in our own history. He’s the eldest son of the Prince Regent George Augustus Frederick, later George IV. In our own history, the Prince Regent had only one legitimate child with Caroline of Brunswick, Charlotte Augusta. The Princess Charlotte died in childbirth in 1817, with the crown ultimately passing to the Prince Regent’s brother William and thereafter to William’s niece Victoria. George, as a character, exemplifies Jikiemi-Pearson’s narrative approach. He’s here because an ahistorical prince-heir allows more epic and more entertaining possibilities for the narrative, quite aside from the star-crossed lovers aspect. And his presence also allows Jikiemi-Pearson to justly excoriate Britain’s violent history of empire and self-justification, and parallel this historical empire with the far-future empire under which the novel’s other protagonist suffers.

Asha Akindele is a self-taught engineering prodigy who has no idea how much of a prodigy she is. The year is (by at least one calendar) 6066: Humans have escaped the dying ruins of their planet only to wind up enslaved by Emperor Thracin, tyrant-ruler of a consortium of a hundred planets. Asha’s one more warm body in the assembly lines of the imperial weapons factories on Gahraan, her days marked by fear and rage and her nights by studying stolen manuals and dreaming impossible dreams of escape. At least until a mysterious and terrifying stranger reveals that she has an elder sister, prisoner (and possible experimental subject) at the heart of the empire, that the fate of all the worlds depends on Asha finding her, and that he’ll kill her mother if she doesn’t go.

Asha is not thrilled to hear this. She’s angry and terrified. Then, while she’s in the middle of stealing a ship to rescue her unknown sister and her mother, Obi suddenly appears.

Obi’s been yanked out of London by a combination of his own curiosity and an artefact set to catapult him to Asha’s future. Crashing into the middle of Asha’s escape, he joins her – and finds that he’s stuck in Asha’s time. At Asha’s side, he quickly finds himself becoming her friend, joining her in chaotic amounts of peril and trouble. More than one prison break is involved. It turns out that Asha and Obi are two of three reincarnated avatars of fated heroes, the subjects of prophecy. Twice before these Heroes (capitalised in the novel) fought for the sake of the worlds. This is the third time, the beginning of the Third Prophecy, which will save all the worlds or doom them. Visions of their pasts – and their past incarnations – haunt them and offer tantalising hints. A mysterious Order of Legends may be allies or enemies. And at the centre of the empire waits an emperor with a weapon that destroys worlds.

Meanwhile, back in Regency London, a dark force is interested in the fragment of Obi’s soul that Prince George has been keeping safe for him. A force so dark and powerful that it draws Obi’s father back from his deep and perpetual avoidance of everything to do with his son and sees him allied with the prince to oppose it. That dark force is linked to Obi’s past incarnations as a Hero.

Jikiemi-Pearson intersperses the action-adventure of Obi and Asha’s present with extracts from and commentaries on a historical-mythological text about the set of prophecies and the Heroic avatars. The mythic register and the presence of time-travel suggests a certain inevitable circularity, the seeds of tragedy-to-come. Against this, counterpose the breakneck space magic adventure and a certain wisecracking tone. This is the first book of a trilogy, and I have no idea what kind of trilogy, in terms of overall tone, it’s going to turn out to be.

Honestly, I found the pace so hectic that hell if I’m sure what’s going on half the time. It has everything and the kitchen sink too: magical prophecies, time travel, reincarnation, evil empires, planet-killing weapons, long-lost family, star-crossed romance, secret princesses, banter and found families, appealing characters, and a vivid burning fury at any and all the justifications of subjugation and injustice. The Principle of Moments’ brimful hectic nature, though, is also a good half of its appeal, in its earnest embrace of the epic, the unabashedly heroic, and the self-consciously mythic. It’s entertaining as all hell, is what I mean to say: It gets the vibe of being twelve years old and watching a lightsaber ignite on the big screen.

I want to quibble with some of Jikiemi-Pearson’s decisions, though: There are details of technology or society that made no sense to me; my sympathy for the figure of Asha’s sister is deeply undercut by the consequences of her choices; and The Principle of Moments is so enthusiastically full of cool shit that it sometimes flirts with incoherence in how it brings it all together. But these are minor quibbles: I’d be more concerned about details in a book that leaned less thoroughly (and less wholeheartedly) into its larger-than-life mythic arc. The Principle of Moments makes a choice not to sweat the small stuff: It has bigger issues to bother with.

An enjoyable debut, and a very promising one, The Principle of Moments has left me greatly interested in what Jikiemi-Pearson does next.

Liz Bourke is a cranky queer person who reads books. She holds a Ph.D in Classics from Trinity College, Dublin. Her first book, Sleeping With Monsters, a collection of reviews and criticism, is out now from Aqueduct Press. Find her at her blog, her Patreon, or Twitter. She supports the work of the Irish Refugee Council and the Abortion Rights Campaign.

This review and more like it in the March 2024 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.