Gary K. Wolfe Reviews How Long ’til Black Future Month? by N.K. Jemisin

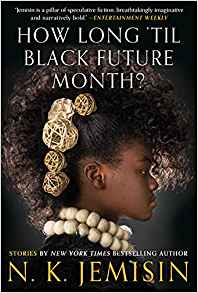

How Long ’til Black Future Month?, N.K. Jemisin (Orbit 978-0-316-49134-1, $26.00, 404pp, hc) November 2018.

How Long ’til Black Future Month?, N.K. Jemisin (Orbit 978-0-316-49134-1, $26.00, 404pp, hc) November 2018.

When an author achieves as much success as N.K. Jemisin has with huge architectonic structures like the Broken Earth and Inheritance trilogies, readers might be excused for greeting her first story collection in either of two ways: gleefully expecting more of the same, or cynically suspecting a series of outtakes or early yeomanlike exercises. I am happy to report that, on the basis of How Long ’til Black Future Month?, the former might be disappointed while the latter should be pleasantly surprised. In her introduction, Jemisin recounts how, back in 2002, she wasn’t really interested in short forms for some very good reasons: they didn’t pay well, they required different skills from the big-ticket novels she wanted to work on, and the chances of a black woman writing about her own concerns and getting published at all were not nearly as good in 2002 as they are now (thanks in no small part to Jemisin’s own successes). The 22 stories that make up How Long ’til Black Future Month?, the oldest dating back to 2004 and four original to the book, comprise a collection that is a bit old-fashioned in the best sense of that term. As we watch Jemisin experimenting with different voices, forms, techniques, settings, and characters in stories that for the most part make use of the familiar traditions of the form: quick narrative hooks, deftly sketched characters, clean linear plots (sometimes wound tight as a mainspring), satisfying payoffs. Jemisin isn’t a literary experimentalist here, but rather someone who enjoys playing with the possibilities of the plotted tale, and it’s fascinating and revealing to watch an author familiar for doing One Big Thing extend her repertoire in unexpected directions.

As far as I can tell, only a couple of the stories, “The Narcomancer” and “Stone Hunger”, return us to the worlds of her novels, the former to the Gujaareh of The Killing Moon and the latter to the devastated landscape of (or after) the Broken Earth trilogy, but neither require prior knowledge of those worlds at all. “The Narcomancer” concerns Cet, a “gatherer” whose task is to perform a sort of extreme unction for the dying, who is confronted with a mystery in which brigands attack villages by causing everyone to fall asleep – a form of narcomancy. It seems a straightforward mystery – and it is, plotwise – but Jemisin manages to introduce themes of gender, power, and rape as Cet joins forces with a member of an order called Sisters of the Goddess, who unexpectedly turns out to be male. It’s the clearest example of a traditional high fantasy setting we’re going to get, although “The Storyteller’s Replacement” – one of the four original stories – embeds a tale of a king seeking to assure his virility by eating a dragon’s heart in an acerbic frame-tale in which a substitute storyteller points out the blunt (and timely) moral: “So many of our leaders are weak, and choose to take power from others rather than build strength in themselves.”

Other stories set themselves in dialogue with specific works or traditions in fantastika. The lead story, “The Ones Who Stay and Fight”, directly addresses Le Guin’s “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas”, capturing that story’s unctuous travelogue style while offering an alternative take on where that isolated child comes from. “Walking Awake”, as Jemisin notes in her introduction, responds to Heinlein’s The Puppet Masters, but offers an alternative view of those crab-like back-of-the-neck parasites, while establishing a theme that seems particularly important to Jemisin, since it recurs more than once in the collection: “All the monsters were right here. No need to go looking for more in space.” “Valedictorian” and its companion piece “The Trojan Girl” are set in an ominous dystopia of ascendant AIs, but the narrative hook in the former tale evokes that of any number of YA dystopias: “Each year, a tribute of children are sent beyond the Wall, never to be seen or heard from again” (what actually happens to them is a good deal more provocative than the usual run of cranky-adult dystopias, however). “Hemosis”, in which a famous author finds his limo driver has been replaced by his “greatest fan,” is Jemisin’s take on Stephen King’s Misery, considerably less violent but no less creepy (though with a refreshingly cavalier ending).

Some of Jemisin’s most intriguing stories, however, draw on the contrasting cultural worlds of the South where she grew up and the more anonymous urban environment where she lives now. The latter tales evoke the paranoia and sheer randomness of urban life, from mysterious unscheduled subway trains that seem to have no riders (“The You Train”) to restaurants that seem to offer every imaginable meal (“Cuisine des Memoires”) to odds-defying accidents and slapstick chains of causation (“Non-Zero Probabilities”, a lark of a tale which reminds us that Jemisin does have a solid sense of humor). “The Elevator Dancer” subtly uses the image of a figure dancing alone in an elevator to gradually reveal an ominous dystopia. But the boldest of Jemisin’s homemade urban myths is also the slightest in plot: in “The City, Born Great”, a homeless graffiti artist finds himself serving as the “avatar” of New York, as it undergoes a kind of birth into consciousness and finds itself challenged by an ancient, almost Lovecraftian “Enemy,” the apparent nemesis of all cities that achieve such birth. It reads like a provocative sketch for a much longer work. Much the same might be said of “Too Many Yesterdays, Not Enough Tomorrows”, in which an apocalyptic shift called the “proliferation” has atomized the world into an endless number of pocket universes, with reality resetting itself every few hours à la Groundhog Day. These are the kinds of stories that invite us to watch a wildly imaginative author noodling around with ideas that are simply fun to play with, whether they actually lead anywhere or not.

It might be a stretch to include “The Effluent Engine” among the urban tales, since it takes place in a steampunk early 19th-century New Orleans, with dirigibles plying the Caribbean, an elaborate scheme to derive cheap energy from the leavings of rum distillation, and a knife-throwing action heroine. But Jemisin also introduces issues of urban crime, white supremacist organizations, and even political revolution (specifically in Haiti). The story might also be counted as one of her southern tales, since a very different New Orleans is the setting of one of the most powerful and haunting tales in the book, “Sinners, Saints, Dragons, and Haints, in the City Beneath the Still Waters” (understandably given pride of place as the concluding selection), in which the unemployed drug dealer Tookie joins forces with a talking lizard (maybe a dragon) to survive – and rescue an elderly neighbor – in the immediate aftermath of Katrina. In a collection that includes some pretty spectacular apocalypses – a posthuman world in “On the Banks of the River Lex” and a dying one in “Cloud Dragon Skies” – this comes across as the most affecting of them all. The immediacy of experienced history also informs another of the strongest tales, “Red Dirt Witch”, in which a poor mother in Birmingham dreams of the coming of a White Lady who threatens her family’s future, but also of a far brighter future for her children and grandchildren, if she can find a way to counter the White Lady’s magic with her own homegrown variety. It’s in many ways the most sentimental tale in the book, with a heroic mother whose sacrifice gives her family hope, but a bit of sentiment and hope in the face of the brittle worlds of the other stories hardly feels out of place. Jemisin’s fiction can be angry or funny or dreamlike or bitter, sometimes all at the same time, but it keeps bringing us back to that observation of a character from “Walking Awake”: all the monsters we really need are right here already.

Gary K. Wolfe is Emeritus Professor of Humanities at Roosevelt University and a reviewer for Locus magazine since 1991. His reviews have been collected in Soundings (BSFA Award 2006; Hugo nominee), Bearings (Hugo nominee 2011), and Sightings (2011), and his Evaporating Genres: Essays on Fantastic Literature (Wesleyan) received the Locus Award in 2012. Earlier books include The Known and the Unknown: The Iconography of Science Fiction (Eaton Award, 1981), Harlan Ellison: The Edge of Forever (with Ellen Weil, 2002), and David Lindsay (1982). For the Library of America, he edited American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s in 2012, with a similar set for the 1960s forthcoming. He has received the Pilgrim Award from the Science Fiction Research Association, the Distinguished Scholarship Award from the International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts, and a Special World Fantasy Award for criticism. His 24-lecture series How Great Science Fiction Works appeared from The Great Courses in 2016. He has received six Hugo nominations, two for his reviews collections and four for The Coode Street Podcast, which he has co-hosted with Jonathan Strahan for more than 300 episodes. He lives in Chicago.

This review and more like it in the December 2018 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.