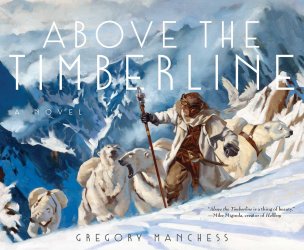

Paul Di Filippo reviews Above the Timberline by Gregory Manchess

Above the Timberline, by Gregory Manchess (Simon & Schuster/Saga Press 978-1-4814-5923-5, $29.99, 240pp, hardcover) October 2017

For nearly twenty years I have been a member of an egroup called Fictionmags, founded by David Pringle, best known for his helming of Interzone. Our broad remit covers “all magazine fiction of any sort.” Populated with passionate readers and bibliophiles, the group naturally tends however to wander all over the literary map in its discussions. Up to his death the famed author and editor Damon Knight was a member. And he once put to the list a very interesting question: “When and why did it cease to be standard practice for adult novels to feature illustrations?” As I recall, no one was ever able to definitively provide an answer to this query. But the question itself remains relevant. Whereas in the early twentieth century the average reader would not be surprised to find, say, the newest book by James Branch Cabell stuffed with pictures from Frank C. Papé, readers in 2017 expect their novels to be 100% prose, no illos. Text with pictures is often deemed a mode of storytelling for kids. True, graphic novels are comprised of both words and drawings, but in a vastly different ratio, and arising from a totally different tradition of publishing.

For nearly twenty years I have been a member of an egroup called Fictionmags, founded by David Pringle, best known for his helming of Interzone. Our broad remit covers “all magazine fiction of any sort.” Populated with passionate readers and bibliophiles, the group naturally tends however to wander all over the literary map in its discussions. Up to his death the famed author and editor Damon Knight was a member. And he once put to the list a very interesting question: “When and why did it cease to be standard practice for adult novels to feature illustrations?” As I recall, no one was ever able to definitively provide an answer to this query. But the question itself remains relevant. Whereas in the early twentieth century the average reader would not be surprised to find, say, the newest book by James Branch Cabell stuffed with pictures from Frank C. Papé, readers in 2017 expect their novels to be 100% prose, no illos. Text with pictures is often deemed a mode of storytelling for kids. True, graphic novels are comprised of both words and drawings, but in a vastly different ratio, and arising from a totally different tradition of publishing.

Consequently, the rare instance today of such a combo–the Griffin and Sabine books of Nick Bantock; Urshurak by the Brothers Hildebrandt; Stardust by Gaiman and Vess; The Invention of Hugo Cabret by Brian Selznick–is bound to draw attention and perhaps puzzled stares. What is this strange hybrid narrative with visuals? I suspect that those folks who like such books really like them, while others are indifferent or even hostile.

The latest such literary mashup comes to us from Gregory Manchess, formerly known primarily for his drawings, and it’s a spectacular success. In the case of Above the Timberline he also supplies the text for the first time, and proves himself an adept of verbal narrative as well as visual storytelling. The book might be most succinctly described as “postapocalyptic arctic dieselpunk love story with polar bears and a hint of Indiana Jones.” If that notion doesn’t get your engines racing, then your sense of wonder has passed its sell-by date.

But before looking into the particulars of the tale, allow me to compliment Saga Press on the intelligent and creative attentions they have lavished on this title. The large trim size allows the art to really pop off the page, and the paper stock is luxurious. Beneath the dustjacket, the boards feature alternate cover artwork. And the placement of the text, in its attractive font, never interferes with the visuals. Bravo!

Our novel kicks off in stellar hook fashion, featuring a battle between two airships above a polar zone known as the Waste. One ship is on an innocent scientific expedition to find a mysterious lost city; the other is under the command of a jealous rival. The rival opens fire. From the doomed innocent ship, in a small prop plane, escapes the archaeologist adventurer Galen Singleton. He crashes out of reach of his pursuers. Then we cut away from his fate–although excerpts from Galen’s journal will continue to crop up to enlighten us.

We cut to an outpost of civilization in the arctic realm, Crescent City. There we meet Galen’s wife and their seventeen-year-old son, Wes. We also get the backstory on this venue. The year is 3518, and over a thousand years ago the Earth underwent a geo-astronomical catastrophe: the magnetic poles reversed, plate tectonics went crazy, and continents slid around like pancakes on a buttered griddle. All of mankind’s accomplishments were buried and lost, but humanity has rebounded to a kind of dieselpunk level of tech. But scavengers still relish digging up artifacts from the lost era. The Waste contains many enticing sites.

When Wes learns of his father’s disappearance, he vows to mount a mission to find and rescue him. But without resources he is forced to enlist a sponsor. The Polar Geographic Society declines, and he must turn to Braeburn Wilkes, once a pal of Galen’s, but now a competitor. Wes makes a hard-pinched deal and departs, carrying with him one of his father’s treasures, the Arktos Device, a mysterious gadget which Wes feels might be valuable in the pursuit.

The rest of the novel is the thrilling and taut tale of Wes’s exploits and mishaps in the snowy wilderness, from crashing his vehicle, to facing leopards, rhinos (!!!) and bears, to dealing with the human inhabitants of the Waste. The natives called the Tukklan (think Herbert’s Fremen) are harsh but perhaps not unfriendly. The monks of the Shadow Moon Monastery are enigmatic and know a lot, but have their own agenda. And then there’s Linea, a beautiful young woman who has a foot in both camps–as well as being a kind of Sheena of the Polar Bears.

Fro a debut novelist, Manchess exhibits a keen sense of plotting and a respectable journeyman’s skill at worldbuilding. His tale exhibits the kind of vigor and respectful nod towards favored old tropes that Philip Jose Farmer’s homages always showed. The family dynamic between the nicely rendered father and son is believable and satisfying, as is the nascent love affair between Wes and Linea. And although Wilkes is offstage for most of the book, he serves as a suitably vile villain at the climax.

But what about the boldly painted art? It’s majestic and captivating, often serving to deliver story details in a silent way that supplements the wordage. If you can imagine the hard-edged fantastic naturalism of James Gurney and Ralph McQuarrie combined with the more impressionistic style of John Berkey, you’ll have a rough idea of Manchess’s prowess. He deploys a good mix of single-page images and glorious double-page spreads that can go from intimate to intimidatingly widescreen. One could almost ignore the text and still get a coherent–albeit diminished–story from the art alone. Together, they pack a killer punch.

Two years ago on his blog, Manchess spoke of “hours and hours of work spent on pacing, page reveals, sculpting sentences for maximum impact, and composing double page spreads.” The labor seems almost inconceivable to a non-artist such as myself. But I can only say I am extremely grateful he poured his heart and soul through his fingers and brush into these fine pages.