Spotlight on: Wang Jinkang

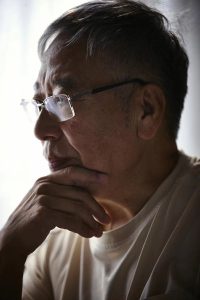

WANG JINKANG (1948—), a Chinese science fiction writer, senior engineer, and multiple Yinhe Award winner. He spent several years in a countryside commune, before being sent to work in an iron foundry and a diesel engine plant. This unique experience sparked his interest in science and engineering, and in 1978, he entered Xi’an Jiaotong University for further studies. Later, he became a petroleum engineer in Nanyang Oilfield. At the age of 44, he published his first work, “Yadang Huigui” [“Adam’s Regression”] (May 1993 Kehuan Shijie). This led to an unprecedented run of successes in Chinese sf awards. He has subsequently published 87 short stories and over 10 novels, totaling more than 5 million words.

Congratulations on your work “Seeds of Mercury” being nominated for the Hugo Award! Could you please introduce what this work is about?

My work “Seeds of Mercury” was created 22 years ago and is recognized as one of the representative works of the new generation of Chinese science fiction (note: the new generation of Chinese science fiction has developed from the 1990s to the present). It was just translated into English last year.

This is a dual-narrative story. The Earth narrative can be considered as a “Confucian story,” encompassing many Chinese moral and social customs. The Mercury narrative is basically a Western biblical story with religious elements.

Earth Narrative: Chen Yizhe, a young businessman with a benevolent heart, suddenly receives an inheritance from his distant aunt, Sha Wu. Sha Wu, a scientist, created a micro-life metallic bodies that can survive in metal solutions. This creation had no practical value, so she could only sustain it with private funds. Three years after her death, the funds ran dry, which means Chen Yizhe received a massive negative inheritance!

Earth Narrative: Chen Yizhe, a young businessman with a benevolent heart, suddenly receives an inheritance from his distant aunt, Sha Wu. Sha Wu, a scientist, created a micro-life metallic bodies that can survive in metal solutions. This creation had no practical value, so she could only sustain it with private funds. Three years after her death, the funds ran dry, which means Chen Yizhe received a massive negative inheritance!

Aunt Sha Wu also had an additional request –

Real life cannot be caged. Conveniently, there is a suitable place for release in the solar system: Mercury, with its lakes of liquid metal. If these micro-lives are released onto Mercury, they might evolve into a Mercury civilization over billions of years.

Chen Yizhe and his wife eventually accept this negative inheritance and seek public assistance. In a televised debate, Chen says that humanity is too lonely in the universe and hopes for a brotherly civilization.

Mr. Hong, highly disabled, grotesque-looking, eccentric billionaire, made a decisive decision to devote his fortune to this cause on one condition – that he accompanies the mission. This person is a contradiction, inherently benevolent yet filled with resentment due to societal discrimination. Chen Yizhe’s initial doubts about him gradually turn into admiration.

The process of spaceship construction accelerates. Mr. Hong’s close friend, Lawyer Yin, reveals that Mr. Hong was in it for the long haul; he plans to freeze himself in Mercury’s polar ice, waking every ten million years to inspect the evolution of the metal life until they develop into a Mercury civilization. With that, Mr. Hong becomes a hero in the eyes of the world.

A dozen years later, Chen Yizhe accompanies Mr. Hong to sow the seeds of life into Mercury’s metallic lakes. He places Mr. Hong in a polar ice cave, along with a platinum statue of Aunt Sha Wu. On distant Earth, Lawyer Yin bids a heartfelt farewell…

Mercury Narrative: On Mercury, the Shawu people evolve, having metallic bodies and no hearing, communicating in binary language through blinking light orifices. These people feed on light. There are no genders, but they must pair and explode upon death to produce offspring.

The Shawu people follow the Shawu Church. The “Holy Book” and “Genesis” state:

The Great God Shawu (actually the female scientist Sha Wu) created the Shawu people, losing the favor of the Father Star.

Before God Shawu’s death, she left an incarnate of Shawu (actually Mr. Hong), who sleeps in the polar ice, avoiding the strong light of the Father Star. Every 41.52 million Mercury years, the Shawu Incarnate awakens and travels around Shawu in the Holy Car. He took pity on the foolishness of the Shawu people and imparted wisdom into their eyes.

Believers often pilgrimage to the Arctic region to worship the Shawu Incarnate, but the lack of light there soon causes them to starve to death. This death is called “drop dead”, and although sunlight can revive them, they become pariahs.

During a period when science was growing under religious oppression, energy box was invented to help the Shawu people reach the Arctic region. Scientist Tu Lala organizes an expedition team to explore the Holy Palace, including his student Qi Kaka. The pope dispatches the priest Hu Baba to supervise.

They find the Holy Palace and the frozen holy body, plunging everyone into a deep religious frenzy, including Tu Lala’s student Qi Kaka. Hu Baba immediately leads the team back to the capital to report to the pope, intending to revive the holy body. Tu Lala stays behind to continue researching.

Tu Lala discovers the instructions left by the Shawu Incarnate and learns the steps for the revival of the holy body. However, his energy box is depleting, and the spare was unintentionally taken by Qi Kaka. Tu Lala is about to experience “drop dead,” and even if revived, he will become a pariah. But for the Shawu Incarnate’s safe revival, he musters all his willpower to survive.

When he awoke, the holy body had been taken away. The compassionate Qi Kaka replaces his energy box but immediately distances himself from the now pariah teacher.

To protect the holy body, Tu Lala endures the public’s hatred and beatings as he rushes to the great god’s revival site, urging the pope to be cautious. But Qi Kaka, now a senior church deacon, angrily exposes Tu Lala’s pariah status, and the fanatical followers beat him into unconsciousness.

The holy body is taken out of the freezer but was immediately destroyed in the high temperature. The pope is terrified. Qi Kaka concocts a malicious lie in a panic, claiming the Shawu Incarnate was a false god, punished by the Father Star! The followers go berserk, completely destroying the holy body.

After the Shawu Incarnate’s death, the Shawu Church quickly reaches its peak. They revere Shawu but degrade the Incarnate as a false god.

An Atonement sect quietly emerges within the Shawu Church, led by a pariah resurrected after drop-dead. They continue to worship the Shawu Incarnate and carefully preserve two holy relics: the charred skull of the Shawu Incarnate and the platinum statue of the female god Shawu.

Despite the new pope Qi Kaka’s severe suppression, the Atonement sect grows because its doctrine awakens a sense of guilt. They silently collect everything related to science. The 180-year-old preacher said before his death that “when the Shawu Incarnate revives in the next millennium, these will be useful. ”

The Atonement sect only follows the Old Testament of the Holy Book, discarding the New Testament. They added a prayer to the Old Testament:

“Shawu People, you killed your birth father, you have sinned.

You shall bear the burden of original sin generation after generation until Shawu Incarnate returns.”

Does “Seeds of Mercury” reflect your hopes or fears for the future? If so, how is this expressed?

Does “Seeds of Mercury” reflect your hopes or fears for the future? If so, how is this expressed?

One can perhaps say that this novel reflects my hopes: I celebrate the love among humans, hoping it can extend to other alien civilizations, wishing that humanity no longer feels lonely. Here’s a small anecdote: there is a detail in the book where the young Chen Yizhe, having just learned to speak, witnesses a cow being slaughtered. He was very distressed as he repeated, “knife, kill, pitiful,” while crying loudly. This is a true story that actually happened to my grandson. It validates the ancient Chinese sage’s saying that “Human nature at its core is inherently good.”

The book also touches on fears, such as the millennium-long dark age brought about by the ravaging of science by religion. However, even such darkness is not absolute because the novel’s ending also depicts the resurgence of science a millennia later.

To express my hopes and fears, I attach them to vivid, three-dimensional life details, like the above real-life anecdote. Although the Mercury narrative is entirely fictional, it is modeled after European medieval history, with the Mercury scientist Tu Lala embodying the spirit of Bruno. Speaking of which, ancient China was relatively peaceful regarding religion, with no religious wars or cruel persecution of “heretics,” but it also didn’t produce modern science. Europe, on the other hand, was the opposite. The world is full of such contradictions.

How has your background as an engineer influenced your science fiction writing?

The engineering career trained me thinking meticulously and agilely, which is quite useful in writing, especially in constructing story frameworks and ensuring the coherence of science fiction ideas.

You are a highly acclaimed and prolific writer in China. Can you introduce some of your other works? Are any of your works available to English readers currently? Will there be more translated works in the future?

You are a highly acclaimed and prolific writer in China. Can you introduce some of your other works? Are any of your works available to English readers currently? Will there be more translated works in the future?

Among the new generation of Chinese science fiction writers, I have the most works in terms of volume, with 21 volumes of collections totaling 6.5 million words. Many of my short and medium-length stories have been translated into foreign languages (English, German, Japanese, Italian, Korean), such as “The Beekeeper,” “A Song for Life,” “Heaven’s Fire,” etc. Not many long works have been translated, with English versions of “Pathological” and a German version of “Life of Ant.” Since the translation of works is mostly led by foreign publishers, I don’t have much information, but I know some works are currently being translated into Japanese and Italian, including the novels “Ancient Shu” and “Ant’s Being.”

You have had a rich career and have served as an official in Chinese writing organizations. How do you view the current state of the art of Chinese science fiction and the development of the publishing industry? What is the position of Chinese science fiction in the global dialogue?

I have been a farmer, miner, woodworker, and design engineer and have served as the vice president of the China Science Writers Association, an honorary position. In China, science fiction writers have no national association but are affiliated with the China Science Writers Association.

For various reasons, Chinese science fiction nearly halted in the late 1980s. The new generation of science fiction developed almost from scratch, growing wild and long neglected by society. After more than thirty years of accumulation, it is now in a “thin outburst” phase, reaching a small peak. In terms of creation, publication, social attention, and author survival environment, it is incomparable to the past. But it is not the pinnacle; the number of authors is still too small, and there are not many classic long works like Liu Cixin’s “The Three-Body Problem.” The adaptation into films is even less ideal.

The development of American science fiction progressed from short, cheap magazine stories to long, bestselling novels. Chinese science fiction is roughly in the late stage of the first phase; short and medium-length stories have reached a world-class level, lacking only in translation and promotion. Apart from “The Three-Body Problem,” long works are relatively weak, but there are some excellent ones. The development of science fiction, unlike all other literary genres, is closely related to the economic and technological development of its environment, especially if it is in a development period. From this perspective, the global position of Chinese science fiction depends not only on the efforts and talents of writers but even more so on the overall trend of China’s development.

What are your sources of literary inspiration or enlightenment?

My works are often referred to as “philosophical science fiction.” This genre highlights the inherent shock value of science and focuses more on the humanistic reflections brought by technology. So, my creation often begins with an inspired thought, followed by the organization of the story and characters.

Is there anything else you wish our readers to know?

I often say that science fiction is inherently the most universal of all literary genres because its source is science, and the scientific system, primarily established by European sages, is unique. Science fiction concerns all humanity. In this increasingly tense political atmosphere, I hope science fiction literature can act as a cool breeze.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.