Cory Doctorow: Unpersoned

AT THE END OF MARCH 2024, the romance writer K. Renee discovered that she had been locked out of her Google Docs account, for posting “inappropriate” content in her private files. Renee never got back into her account and never found out what triggered the lockout. She wasn’t alone: as Madeline Ashby recounts in her excellent Wired story on the affair, many romance writers were permanently barred from their own files without explanation or appeal. At the time of the lockout, Renee was in the midst of ten works in progress, totaling over 200,000 words (Renee used Docs to share her work with her early readers for critical feedback).

AT THE END OF MARCH 2024, the romance writer K. Renee discovered that she had been locked out of her Google Docs account, for posting “inappropriate” content in her private files. Renee never got back into her account and never found out what triggered the lockout. She wasn’t alone: as Madeline Ashby recounts in her excellent Wired story on the affair, many romance writers were permanently barred from their own files without explanation or appeal. At the time of the lockout, Renee was in the midst of ten works in progress, totaling over 200,000 words (Renee used Docs to share her work with her early readers for critical feedback).

This is an absolute nightmare scenario for any writer, but it could have been so much worse. In 2021, “Mark,” a stay-at-home dad, sought telemedicine advice for his young son’s urinary tract infection (this was during the acute phase of the covid pandemic, all but the most urgent medical issues were being handled remotely). His son’s pediatrician instructed Mark to take a picture of his son’s penis and upload it using the secure telemedicine app.

Mark did so, but his iPhone was running Google Photos, with auto-synch turned on, so the image was also uploaded to his private Google Photos directory. When it arrived there, Google’s AI scanned the photo and flagged it for child sexual abuse material. Google turned the issue over to the San Francisco Police Department, and furnished the detective assigned to the case with all of Mark’s data — his location history, his email, his photos, his browsing history, and more.

At the same time, Google terminated Mark’s account and deleted all of their own copies of his data. His phone stopped working (he had been using Google Fi for mobile service). His email stopped working (he was a Gmail user). All of his personal records disappeared from his Google Drive. His Google Authenticator, used for two-factor authentication, stopped working. Every photo was deleted from his Google Photos account, including every photo he’d taken of his son since birth.

Mark’s son got better and the SFPD exonerated Mark, but the police detective was unable to contact Mark to tell him so because he had no email and no phone service. Ultimately, the detective mailed a letter to Mark’s house to tell him that he wasn’t suspected of abusing his son.

When Kashmir Hill reported on Mark’s story for The New York Times, Google defended its decision to permanently delete all of Mark’s data and cut him off from every account for every service he’d ever signed up for (without his email, SMS, and Authenticator codes, Mark was locked out of virtually every digital service he used). They said that Mark’s photos included an image of “a young child lying in bed with an unclothed woman” (Mark believes this is a reference to a photo he took of his wife and son asleep together in the dawn light).

Mark isn’t the only person this happened to. Hill’s article tells the story of others who were caught in Google’s dragnet, whose appeals to reason were ignored, and whose lives were demolished by the decision of a single, very large tech company that could do the same to you or me at any time, without any recourse.

–

What should we do about this?

Well, we could regulate whom the platforms must extend service to and force them to provide service to people they believe to be pedophiles who use their services to traffick in child sex-abuse material, or to make ransomware threats, or to conduct sextortion, or to spread malicious software, political disinformation, or calls for genocide. We could force them to provide service to harassers who target their other users and chase them off their platforms.

I don’t like that idea, and I imagine that the way I phrased that previous paragraph gives you a pretty good idea as to why.

What about giving users some data rights? Both the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) give the public a legal right to demand their data from platforms. So far, this has proven pretty useless. Europeans who demand their data under the GDPR get giant, unusable database dumps that are basically impossible to make sense of on their own. Theoretically, some rival to the tech monopolies could build an importer that could make sense of these blobs, ingesting them and setting up a user with all their files on a new service. The problem there is that tech monopolies don’t have rivals (monopolies, remember?).

The dumps under California’s data-protection law aren’t any more useful. I get an ungodly amount of spam from Mailchip, the giant marketing email provider owned by the tech monopolist Intuit. A vast horde of jerks has imported my email address into their Mailchimp marketing lists. Mailchimp has long refused to provide its victims with a list of all the mailing lists they’ve been added to, with the option to unsubsubcribe from spammers’ lists, so I recently tried to use CCPA’s data rights to force them to cough up a list. I got a blob with thousands of folders, each containing multiple files that showed me that I was on over 1,000 Mailchimp lists, but didn’t provide the names of any of these lists, or any way to unsubscribe from them.

Even if we could get data-dumps to work, that still wouldn’t fully resolve Mark’s plight — he doesn’t just want his old data back, he wants to be able to receive email and phone calls again.

As it happens, we have a pretty good solution to the phone number problem, provided your carrier will cooperate with you. For more than 20 years, Americans have had the legal right to demand that their carrier switch their phone number over to a rival service. All you need to do is set up an account with a new carrier and call your old carrier and demand a “port out.” After a few minutes’ conversation (in which they’ll beg you to talk to a “retention specialist” who’ll offer you the sun, the moon and the stars not to take your business elsewhere), you will initiate a process to transfer your number to your new carrier, generally within minutes.

This number porting system is a form of legally mandated interoperability (“interoperability” is when two things work with each other, like how your web-browser can connect to any web-server, or your shoes will work with any shoelaces, or your car will run on any brand of gasoline).

In the EU, the new Digital Markets Act (DMA) brings legally mandated interop to online services, requiring them to operate gateways that let other services connect directly to them, so both their users can exchange data with each other.

Predictably enough, the big platforms have lost their minds over this. Their argument is that when they kick a user off of their service, they don’t want to ever hear from that user again. If you’re a harasser, a child abuser or a ransomware creep, they want you off their platform, period.

This is a superficially plausible argument — unless you think about K. Renee or Mark. The platforms’ argument sound like “We don’t want to be forced to provide service to people we dislike” (a reasonable proposition), but when they block interoperability, they’re really saying “We want to be able to declare some people to be unpersons, disconnected from our billions of users, even if they’d like to talk to one another.”

Not only that, but they’d like the unpersoning process to be unilateral and frictionless. They don’t want to have to get an injunction to prevent a ex-user from communicating with users on their platform who want to hear from them. They want to compile and administer their own blocklists in private, according to their own rules.

They’re like a landlord that wants the right to evict you and the right to prevent you from forwarding your mail after you’re gone.

I’m not saying that no one commits crimes so grave that we, as a society, shouldn’t cut them off from some or all of the internet. I’m just saying that those calls should be democratically accountable and based on due process, not private policies carried out by nameless corporate functionaries.

Interoperability could balance out the right of a platform to kick people off whom they dislike, without giving them the power of handing out Internet Death Penalties. Under the DMA — or US equivalents, like the ACCESS Act, which has been repeatedly introduced in the House and Senate — Google, Facebook, or Apple could still kick you off, but they’d have to give you your data and they’d have to forward your communications to other services that you sign up for. If they didn’t want to do that — if they thought your data contained child sex abuse material or if they believed you were a harasser — they’d have to get an injunction against you. In other words, society would decide who didn’t deserve their data or communications, not a corporation.

There are already voluntary versions of this system. Mastodon, the open, federated alternative to services like Twitter, has a built-in system for message forwarding. If you want to leave one Mastodon service and set up shop on another, you can export a file from your old server with all the addresses of everyone you follow and everyone who follows you, and import than into a new server, and within moments, you’ll be receiving your messages again. The people whose addresses appear on that list don’t even have to know about it, no more than the people you talk to on the phone need to know that you’ve changed carriers.

We could enshrine this Mastodon feature in law, through an amendment to the CCPA: “If you operate a Mastodon service and you kick a user off (or if a user quits), you have to give them the file that lets them get set up somewhere else.”

Note that this could go wrong. The ability to number-port has spawned a whole criminal underground devoted to “SIM swapping” attacks, in which carriers’ customer service reps are bribed, coerced, or tricked into assigning your phone number to someone else, usually as a prelude to hijacking your email or banking account (this is why SMS-based authentication is considered weak).

But the answer to SIM swapping is to improve security at the carriers — not to make it harder to leave a phone company you don’t like. Having your account hijacked is bad — but so is having it disconnected. Whether you’re a rural fisherman in the global south who uses WhatsApp to sell your catch, or a San Francisco dad who uses Google to keep your finances, store your family photos and email clients, disconnection is a serious, life-shattering hardship.

When the service providers say they want to be able to choose whom they give accounts to, I’m right with them. There’s plenty of people out there I wouldn’t welcome on my server. But when they say they want to eject some of those users and deny them forwarding service and their own data, they’re saying they should have the right to make the people they don’t like vanish. That’s more power than anyone should have — and far more power than the platforms deserve.

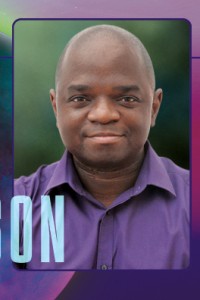

Cory Doctorow is the author of Walkaway, Little Brother, and Information Doesn’t Want to Be Free (among many others); he is the co-owner of Boing Boing, a special consultant to the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a visiting professor of Computer Science at the Open University and an MIT Media Lab Research Affiliate.

All opinions expressed by commentators are solely their own and do not reflect the opinions of Locus.

This article and more like it in the August 2024 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.