The Year in Review 2023 by Ian Mond

2023 in Review: Best. (Reading). Year. Ever.

2023 in Review: Best. (Reading). Year. Ever.

I’ve remarked on the book-lag I experienced since the COVID lockdown, which saw my reading drop off a steep cliff. In 2023, I’ve felt more like my book-loving self, reading close to 90 books (compared to 60 last year). It helps that this has been an extraordinary year for fiction, the best I’ve experienced since penning reviews for Locus. I’m aware recency bias is a thing, so thankfully, I have an objective source (well, objective to me) – my super-secret Excel sheet where I mark every book I read (those who follow me on Goodreads will know I do not use the star system). I typically dole out one ten a year, maybe two. This year: seven. That’s right; I awarded seven novels full marks. It’s possible I’ve gone soft, though I’ve never been the harshest critic. The truth is, it’s been a magnificent year for fiction, the sort that reminds you why you fell in love with stories.

Of that peerless bunch of seven, I still had a favourite. Terrace Stories by Hilary Leichter, the follow-up to her outstanding debut Temporary, is a mosaic novel broken into four parts, each labelled with an architectural design or concept (‘‘Terrace’’, ‘‘Folly’’, ‘‘Fortress’’, and ‘‘Cantilever’’). In the first story, ‘‘Terrace’’, a married couple moves into a tiny apartment with their newborn. When Annie – the wife – invites her co-worker Stephanie over for a visit, the nappy cupboard, impossibly, opens into a terrace complete with a chair and table, a miracle that only occurs in Stephanie’s presence. The other three parts, which spin out from this surreal, marvellous first story, are told from the perspectives of Annie’s parents, Stephanie, and Annie’s daughter, Rose. While Temporary was wall-to-wall absurdity about the nature of employment in the 21st century, this beautiful book, while wonderfully strange, feels more mature and nuanced: an emotionally wrenching portrait of love and family, infidelity and estrangement.

Of the other six, it’s a toss-up which one I liked most. So, in no particular order:

In Ascension by Martin MacInnes. If anyone asks you what happened to the ‘‘sense of wonder’’ in science fiction, point them to this novel (which was longlisted for the Booker Prize). Starting with the mysteries of the deep sea and ending with the outer reaches of space, MacInnes’s meditation on the transcendent is also a powerful tale about Leigh’s fraught relationship with her abusive father, her distant mother, and her estranged sister.

Conquest by Nina Allan. No one deconstructs genre fiction like Allan, and this novel feels like an apogee of sorts, tugging on thematic threads from her previous books. The plot is straightforward: Frank, a devotee of conspiracy theories, including the belief that Earth has been invaded as foretold in an obscure ’50s science fiction novella, goes missing on a trip to Paris. His girlfriend, Rachel, hires a private investigator, Robin, to find Frank. What’s simple unfolds into a polyphonic delight with essays on the work of Shane Carruth and Hans Werner Henze, while the middle of the novel is handed over to the SF novella that has so obsessed Frank. Allan’s ability to tie it all together in a manner that’s intellectually and emotionally satisfying is, frankly, remarkable.

Him by Geoff Ryman. Talking of remarkable, Ryman pulls off the impossible. He imagines an alternate history where Jesus was born female but identified as a man. It’s a premise designed to catch the attention and the ire of culture warriors. Instead, it’s a beautifully told story infused with humanity and compassion: a mother coming to terms with her son’s transition and who also happens to perform miracles and call himself the Son of Adam. It’s an extraordinary, brave, nuanced novel; the last five pages are simply breathtaking.

I Am Homeless if This Is Not My Home by Lorrie Moore. Imagine this: Our protagonist, Finn, undertakes a road trip with his ex-girlfriend, Lily, who happens to be (a) dead – or more precisely, death adjacent, having taken her own life – and (b) wearing clown shoes – she was buried in them. I’ve not read Moore before, but after this, mark me down as a fan. Partly, it’s because Moore knows how to craft the perfect sentence, partly because the dialogue between Finn and Lily is heartbreaking and hilarious in equal measures and partly because Moore, somehow, encapsulates the sheer messiness of contemporary life. Just spectacular.

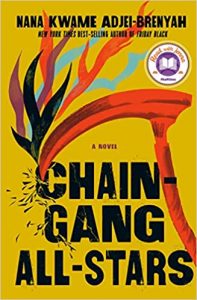

Chain-Gang All Stars by Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah. The first of two sublime debuts in my 10/10 list. Chain-Gang has appeared on all manner of ‘‘Best of Years’’ lists, and for good reason. Adjei-Brenyah presents us with a dystopian America where the Industrial Prison Complex turns to bread and circuses to make a buck by offering a pardon to hardened criminals who can survive three years of death matches. It’s a novel told through a multitude of perspectives (the fans, the activists, the prisoners) that unpacks the cruelty and injustice of America’s prison system. And, incredibly, it’s also a queer love story.

Chain-Gang All Stars by Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah. The first of two sublime debuts in my 10/10 list. Chain-Gang has appeared on all manner of ‘‘Best of Years’’ lists, and for good reason. Adjei-Brenyah presents us with a dystopian America where the Industrial Prison Complex turns to bread and circuses to make a buck by offering a pardon to hardened criminals who can survive three years of death matches. It’s a novel told through a multitude of perspectives (the fans, the activists, the prisoners) that unpacks the cruelty and injustice of America’s prison system. And, incredibly, it’s also a queer love story.

The Saint of Bright Doors by Vajra Chandrasekra. A splendid, imaginative debut about absent fathers, abusive mothers, altered realities, group therapy, and religious extremism. This novel starts as one thing, becomes another, and then changes again. A narrative in flux is in keeping with the central premise where reality has been altered. But it’s also not a thing that’s easy to pull off. We’re able to go along for the ride because of Chandrasekra’s rich voice, but also the characters, especially our protagonist Fetter and his complex relationship with his mother, his even more complicated relationship with his Godly-father and his everyday relationships with the people in his life, activists, lovers, people in high and low power. Oh, and there’s a twist. A stupendously good twist!

It doesn’t end there. Stephen Markley’s The Deluge would have topped my list in any other year. Clocking in at 900 pages, The Deluge was, by far, the longest book I read, and I loved nearly every minute of it. Starting in 2010 and ending in the 2040s, Markley chronicles our inevitable climate catastrophe from the perspective of six characters, including an ecological terrorist, a charismatic activist, a neurodivergent maths nerd, a curmudgeonly oceanographer and a down-and-out drug addict. In setting the novel now rather than in the distant future, Markley’s narrative has a visceral immediacy that makes the cinematic set pieces (like LA burning to the ground) absolutely terrifying. The book has flaws, such as a rushed ending (which is ironic given the length), but those issues pale when considering this remarkable, propulsive novel in its anthropogenic totality.

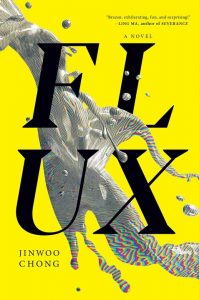

It was also a magnificent year for debut novels. Aside from the two novels I’ve mentioned, five others caught my attention, beginning with Flux by Jinwoo Chong, which didn’t get the recognition and hype I believe it deserved. The novel blends Elizabeth Holmes (of Theranos fame) with Russian Doll (Season Two) and Charles Yu’s Interior Chinatown to deliver a moving novel about childhood trauma and identity. The story centres on Brandon, who lost his mother when he was eight and is obsessed with a 1980s cop drama (and its Clint Eastwood/Asian-identifying hero). Three days before Christmas, Brandon is fired from his job, falls down an elevator shaft, and is offered a job at a tech start-up seeking to develop a battery that provides perpetual energy. The narrative shifts between the present and future, though to say more would spoil Flux’s numerous surprises and insights. Dazzling by Chikodili Emelumadu is a flavoursome stew of a novel steeped in Igbo spirituality and traditions. It’s about two 12-year-old girls. One, Treasure, makes a deal with a spirit to have her father returned from the afterlife, while the other, Ozoemena, is marked by the spirit of her Uncle to adopt the role of the leopard and defend her people. Emelumadu’s singular voice affords the narrative an infectious, vibrant rhythm. Chlorine by Jade Song, like Dazzling, is a coming-of-age story. It’s about Ren, a Chinese Americanteenager who swims competitively and believes she’s a mermaid. It’s a raw, discomfiting narrative about gender and cultural identity that powerfully displays the tension between how a young person sees themselves and how they are perceived by everyone else. Marisa Crane’s ferocious I Keep My Exoskeletons to Myself has the intriguing conceit of a dystopian America where criminals are marked with an additional shadow. Our protagonist, Kris, has a second shadow (for reasons she’s not willing to divulge), but horribly, so does her newborn daughter, who is ‘‘guilty’’ of ‘‘murdering’’ her mother in childbirth. With that conceit, Crane proffers a passionate story about the importance of community, family (not necessarily biological), and allies willing to stand against oppression and hate. A late entrant (only because I just finished it) is Dolki Min’s mordantly funny, sexy, and gory Walking Practice (translated by Victoria Caudle). A shape-shifting alien crash lands on Earth, where after a couple of months of toughing it out, they are forced to use a dating app to find intimacy and a source of food. Yes, they are a gender-bending lovelorn flesh eater with strident views about identity. I loved it.

2023 was a fine year for alt-histories. Of course, there’s the magnificent Him, but I also enjoyed Francis Spufford’s Cahokia Jazz and Catherine Lacey’s Biography of X. In the former, a noir crime story with dollops of jazz, the historical pivot point hinges on the Cahokia nation not being wiped out by European settlement and especially the disease brought by the colonists. Our hero, Detective Joe Barrow, has the build and countenance of a local but is new to the area, the outsider who learns truths about themselves. Spufford does a terrific job of bringing to life the sovereign state of Cahokia while remaining true to the noir aesthetic. And the jazz scenes are just incredible. Regarding the latter, Lacey presents a deeply researched, intricately crafted, and extremely intelligent fictional biography of an enigmatic artist named X. Rather than slide X into a history we recognise, Lacey sets the novel in an America where, in 1945, the Southern States split from the rest of the country and formed a theocratic nation. It’s extraordinarily ambitious, a novel about the slipperiness of identity that also deconstructs the inherent flaws of a biography.

2023 was a fine year for alt-histories. Of course, there’s the magnificent Him, but I also enjoyed Francis Spufford’s Cahokia Jazz and Catherine Lacey’s Biography of X. In the former, a noir crime story with dollops of jazz, the historical pivot point hinges on the Cahokia nation not being wiped out by European settlement and especially the disease brought by the colonists. Our hero, Detective Joe Barrow, has the build and countenance of a local but is new to the area, the outsider who learns truths about themselves. Spufford does a terrific job of bringing to life the sovereign state of Cahokia while remaining true to the noir aesthetic. And the jazz scenes are just incredible. Regarding the latter, Lacey presents a deeply researched, intricately crafted, and extremely intelligent fictional biography of an enigmatic artist named X. Rather than slide X into a history we recognise, Lacey sets the novel in an America where, in 1945, the Southern States split from the rest of the country and formed a theocratic nation. It’s extraordinarily ambitious, a novel about the slipperiness of identity that also deconstructs the inherent flaws of a biography.

In my humble opinion, the best collection of 2023 was Matthew Cheney’s remarkable The Last Vanishing Man and Other Stories. It’s an assured, carefully composed collection that tends toward the grim and horrific but, importantly, is never an exercise in bleakness. Instead, Cheney’s clear-eyed, immersive prose provides a fascinating insight into obsession, violence, and loneliness. This is a collection that deserves award recognition. So does Fortunate Isles by Lisa L. Hannett: a collection of stories set in and around the liminal seaside village of Barradoon. Hannett draws on Celtic and Norse myths that are not part of my cultural background but come alive in her skilful hands and resonate in unexpected ways. Unexpected is a term I’d apply to Yukimi Ogawa’s debut collection, Like Smoke, Like Light: Stories. Unexpected because Ogawa is a Japanese author who writes almost exclusively in English, and unexpected because these stories, which deal with identity and injustice and discrimination and class, are wildly inventive, reminding me of the work of Karin Tidbeck. Izumi Suzuki is a Japanese writer who sadly passed away in the mid-80s and has only now had her subversive genre fiction translated into English (thank you, Sam Bett, David Boyd, Daniel Joseph and Helen O’Horan). Hit Parade of Tears: Stories follows Terminal Boredom in collecting all her published stories. While not setting out to be a trendsetter, Suzuki’s radical science fiction, ranging from the abstract to the disturbing, paved the way for other women genre writers in Japan like Yukimi Ogawa.

My two favourite horror novels both had a distinct ecological bent. Pink Slime by Uruguayan author Fernanda Triás (translated by Heather Cleary) takes place in a Port City where a toxic algae with flesh-flensing properties is choking the surrounding area. Against this backdrop, our unnamed narrator is a nanny for a boy with a syndrome where he can’t regulate his appetite – he is always hungry. The novel is hard to read but also hard to put down. It’s a genuinely unsettling example of eco/body horror that’s also a commentary on motherhood. Lamb by Matt Hill is similarly disturbing, replacing toxic algae with a mould that gets in every nook and cranny, especially the human body. But while the ick factor is very high, like Pink Slime, this is a beautiful and elegiac meditation on parenting – in this case, the deep connection between a mother and son.

2023 also saw the publication of two standout non-fiction books. Niall Harrison’s essay collection, All These Worlds, assembles a decade’s worth of criticism from one of the field’s most important (if not the most important) critics. Harrison, at his height, shaped genre criticism – he certainly inspired me – and it was gratifying to be reminded of the incisive brilliance of his work. I’m so glad to see his criticism in Locus’s pages (amongst other venues such as Strange Horizons). I missed him. Then there’s A Traveller in Time: The Critical Practice of Maureen Kincaid Speller, edited by Nina Allan. As you should be aware, Maureen sadly and tragically left us far too early back in September 2022. While Niall inspired me, Maureen moulded me, supporting and editing my early reviews for Strange Horizons. This is a magnificent collection of her criticism, only enhanced by a suite of moving, beautiful essays from Nina Allan, Jonathan McCalmont, Dan Hartland, Aishwarya Subramanian, and Maureen’s husband, Paul Kincaid.

The quality of work published in 2023 runs so deep that I’ve run out of space to remark on them all. So, in one excited breath, I call out: Lone Women by Victor LaValle (a cracking story); Death Valley by Melissa Broder (I love an impossible cactus!); Let Us Descend by Jesmyn Ward (oh, the gorgeous prose); Hopeland by Ian McDonald (there’s a storm event in this novel that’s one of the most dramatic things I read this year); The Thing In The Snow by Sean Adams (Kafkaesque weirdness in a research institute in the middle of nowhere); Shy by Max Porter (a sensitive portrait of a complex mind with a hint of the otherworldly); How to Sell a Haunted House by Grady Hendrix (the best contemporary horror scribe produces another creepy banger); Again and Again by Jonathan Evison (storytelling at its most pure); and last, but very much not least Bang Bang Bodhisattva by Aubrey Wood (queer cyberpunk with sharp teeth).

It’s now over to you, 2024. What have you got to offer?

Ian Mond loves to talk about books. For eight years he co-hosted a book podcast, The Writer and the Critic, with Kirstyn McDermott. Recently he has revived his blog, The Hysterical Hamster, and is again posting mostly vulgar reviews on an eclectic range of literary and genre novels. You can also follow Ian on Twitter (@Mondyboy) or contact him at mondyboy74@gmail.com.

This review and more like it in the February 2024 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.