Ai Jiang: Where the Ghosts Live

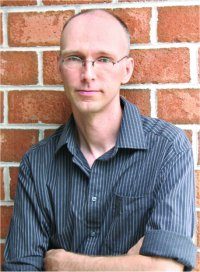

AI JIANG was born June 18, 1997 in Fujian, China, and emigrated to Canada with her family at age four. She attended the University of Toronto, the Humber School for Writers, and the Gotham Writers’ Workshop, and earned her MFA in creative writing from the University of Edinburgh in 2022.

AI JIANG was born June 18, 1997 in Fujian, China, and emigrated to Canada with her family at age four. She attended the University of Toronto, the Humber School for Writers, and the Gotham Writers’ Workshop, and earned her MFA in creative writing from the University of Edinburgh in 2022.

She began publishing work of genre interest with “Hello’’ (2021) in The Dark, and more than 35 stories have since appeared in F&SF, Uncanny, and other genre publications, as well as literary magazines. Notable short works include Nebula Award finalist “Give Me English’’ (2022) and novelette I AM AI (2023). Some of her short work was collected in Ai Jiang’s Smol Tales from Between Worlds (2023). Debut novella Linghun appeared in 2023, and novella A Palace Near the Wind is forthcoming in 2025.

Jiang is a poet as well; “We Smoke Pollution’’ (2022) won an Ignyte Award. She also guest-edited the October 2023 issue of Apparition Literary Magazine. Jiang is the recipient of the Odyssey Workshop’s 2022 Fresh Voices Scholarship.

She lives in Toronto, Canada with her spouse.

Excerpt from the interview:

“I AM AI is a bit of a meta-cyberpunk-biopunk-dystopian fiction, about a cyborg named Ai who is posing as an AI, in a very capitalist society that favors efficiency and productivity over humanity. I definitely like to jump between genres, but not so much just because I want to, but because some of the ideas that feel very close to me, or important to me, feel right being tackled in those specific genres. For me, both Linghun and I AM AI, even though they are vastly different, are both exploring things that either confuse me or that I want to explore, personally, or things I care about.

“In I AM AI, it’s toxic productivity and work culture that forces people to be less and less human and treated more and more like machines. It is based on ghostwriting work I did before. I used to work as a ghostwriter; I won’t say what for, but I wrote a bunch of things as a ghostwriter. That was my full-time job, but only for a little bit, because the burnout rate was far too high. They wanted to move me to a position where I’m not doing the writing but doing most of the managing and editing, but I was like, ‘No, I do not want to be in this industry anymore.’ It was paid by page; for some ghost writers, I know it’s paid by word. The more you write, the more you get paid, and if you pass a certain word threshold, you get a bonus, things like that. There would be months where I would be writing a total of 200K words or something like that, just churning out content. The quality had to be good, but it didn’t have to be very, very good. When you write your own work, you do a lot of deep thinking, deep research, brewing on your arguments and ideas and stuff before you write it. For this, it’s more like you become a content mill, but you still have to have some form of soul in your writing, in a way. So, not completely content mill. But, the more you write, the more you get paid, and it was that kind of culture, where you’re just pushing yourself to the absolute limit trying to get the words down as fast as you can.

“The protagonist does the exact same thing. She is in a society that is overrun by these content-churning programs that are very cheap. The only thing that sets her apart is she still has some form of humanity left, and that is why people would also want to hire her for her services. The thing is, she has to compete with these companies that have apps that do the same thing as her, but with slightly less humanity, for a much cheaper price. So, she has to charge much lower prices, but then also work much harder than machines do. So, she slowly replaces parts of her body; or, that’s what she’s trying to do. Her brain for a faster processor, things like that. Her heart, so she doesn’t have emotions, so she can just work, work constantly. Replacing her stomach so she doesn’t have to eat too much or could use other, cheaper fuel in this dystopian society where real food cost is obviously much more than synthetic things like plastic.

“Both with my short stories and my books, I almost never read them again. Revision is like pulling teeth; I never want to read it after I’m done. My first novel’s been like that. I’m on my third revision, I think; mostly it’s adding things, because as a short story writer, I tend to write very, very sparse, almost skeletal first drafts. My first novel, draft zero was 45k, then the first draft was 65k, second was 70k. I’m really, really pulling teeth now trying to get the word count to be higher, and adding in more – in short stories, you don’t have to expand a lot of the world-building stuff. It can be in the background and you can feel the fully fleshed world within the story. With novels, people are like, ‘No, I want to know these little details, exactly what’s going on.’ Or, ‘It’s too short. It needs to be longer. You need to have all these detailed history things.’ And I’ll be like, ‘All right; fine.’

“When I put together the collection Smol Tales From Between Worlds, I organized the content and theme without rereading them. This collection mainly curated my early works, a lot of things I wrote that did not get as much attention when I first became a writer. It’s more like a way to reflect on my writing journey, rather than putting all my best, best works in one collective volume. This collection also came with author notes at the end of each and every story, to explain the intent and my mindset while writing those stories. (Author’s Note in fine print: ‘I hate all of them!’–I’m kidding but also not because imposter syndrome is a pesky thing) I picked stories that had a lot of sentimental value in that they explored what was personally important to me as a person, and it reflected in my writing, especially my early writing.

“When I was first beginning out as a writer I did write – and I still do write – a lot about identity, immigration, things like that. It does come out in the worlds I’ve built and the characters I write. Whatever I am feeling at the time – familial conflicts or otherwise; or, things that I’m thinking a lot about – duty, responsibility. I feel like society, expectations, sociopolitical pressures, things like that, it all comes out in these stories. But, in these stories, because my craft back then is not nearly as refined as my craft now – I don’t want to say they didn’t do a good job of bringing the themes out, but they feel a lot more muted or hidden or clumsily executed. The writing feels definitely a lot rawer, or authentic, without a lot of fine-combing through it.

“I still come back to the same topics. I don’t necessarily think my approach has changed, but I think it has become more complicated. The more you think about a topic, the more dimensions of that topic you see, and the more you read about that topic and talk to other people about that topic, the more your idea of that topic changes and becomes layered. Let’s say, what I thought about womanhood when I first started short stories and craft and all that is very different from my idea of womanhood now.

“I have some novellas coming out. One is A Palace Near the Wind; it is kind of complicated because it is about everything and nothing all at once. I feel like when I write long form, I want it to be everything. Unlike in short form, where you can focus very narrowly on one thing, and only explore that one thing, or that one specific part of that one theme. My intention was to explore nature vs. industrialism, but not very specifically historic, like any specific historic event. But just in general, in terms of what I have seen and experienced in my life about nature’s destruction and the rise of industrialism and how it has changed our world. My grandma’s old village was torn down because the buildings were really old, so they had to be either renovated or changed into condos, and because of rising population and things like that, they need new buildings. So, where she used to live was six different villages put together, and very, very old, historic buildings that were falling apart. Now, they’re high-rise condos with the same people living in them. It’s very different because the place she used to live in, you could see into people’s bedrooms; you open your window, you see someone undressing kind of situation. But now in the condo, it’s quite separated, do you know what I mean? You can’t just look out the window and shout at your neighbor, ‘Hey, good morning!’ I wanted to kind of explore that in this book. The main character is a princess of the natural world; she is a tree princess. It’s basically nature personified versus industrial people personified, against one another. It’s kind of like – I don’t want to give too much away – a battle for land, almost. No matter what I write, some form of immigration sneaks in there, the experience of immigration. I try to explore different concepts that may not seem like my own experience through a lens that is my own experience. So I explore the people of the trees, their loss of land, as immigration, a loss of home.

“I feel like whenever I write science fiction – or in the broad realm of science fiction, in general – it is tackling very present, capitalist, and societal issues. But in fantasy, it is more broad-sweeping. Even though this sounds more like climate change issues, there is a philosophical musing to it. My strength as a writer is big ideas, trying to explore them through a very different lens than how they’re traditionally explored – or, at least, I would like to think so. It always starts with an idea in mind, or some concept that really interests me, and then I try to figure out how I can further complicate it or turn it on its head, or explore it a different way.

Interview design by Stephen H. Segal.

Read the full interview in the December and January 2023 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.