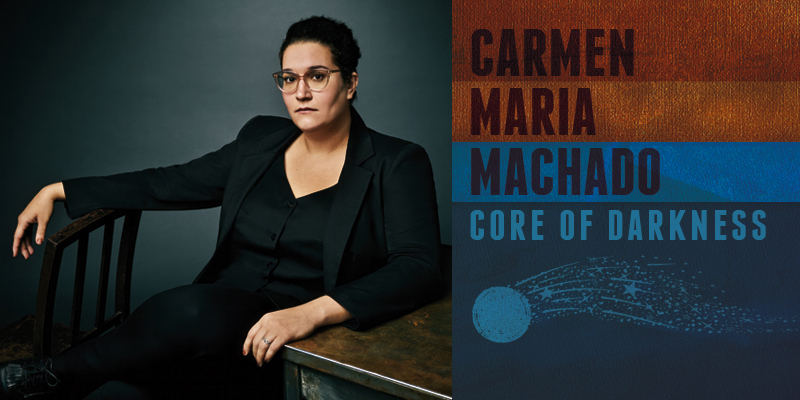

Carmen Maria Machado: Core of Darkness

CARMEN MARIA MACHADO was born July 3, 1986 in Allentown PA. She studied at American University in Washington DC, graduating with a degree in photography in 2008. She attended the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, graduating with her MFA in 2012, the same year she attended the Clarion Workshop. Machado has received fellowships and residencies from the Speculative Literature Foundation, Yaddo, the Millay Colony for the Arts, and other programs. She was a 2019 Guggenheim fellow for fiction.

Machado began publishing work of genre interest with “Difficult at Parties” (2012), and notable short works include Shirley Jackson and Nebula Award finalist “The Husband Stitch” (2014) and Shirley Jackson Award finalists “The Resident” (2017) and “Blur” (2017). Machado effortlessly moves between literary and genre venues, with work appearing in Conjunctions, Granta, and Tin House, as well as Lightspeed, Nightmare, Strange Horizons, and Uncanny, among other publications.

Her debut collection Her Body and Other Parties: Stories (2017) was a National Book Award, World Fantasy, and Otherwise (then Tiptree) Award finalist, and won the Shirley Jackson Award and Crawford Award. A second collection, A Brief and Fearful Star, is in progress.

Machado’s memoir In the Dream House (2019) won the Folio Prize. She edited the 2019 volume of The Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy, and co-edited upcoming non-fiction anthology Critical Hits, about video games, with J. Robert Lennon. Her essays and articles have appeared in the New Yorker, the New York Times, the Paris Review, and other prestigious outlets.

This semester, she is a visiting associate professor at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, teaching both a fiction workshop and a seminar on the literature of haunted houses.

Excerpt from the interview:

“In the Dream House is a memoir about an abusive, queer relationship I was in during my early twenties. In its aftermath, I was really struggling, for all kinds of reasons but also because I couldn’t find my own experience reflected in any published work. Because there are memoirs about abuse, and abusive relationships, and intimate partner violence, but there really were not any about queer intimate partner violence. There was one book of poetry and a couple of essays floating around, and I was like, ‘Oh, I guess I need to write that.’ So yeah, it’s a symphonically structured memoir where each chapter has a genre element as an interrogating tool. There are a few chapters that are a couple of pages long, and couple that are maybe four pages long, but most chapters are one or two pages long. So, it’ll be ‘Dream House as Blank’: ‘Dream House as Haunted House’, or ‘Gothic Novel’, or ‘Time Travel’. Then I use elements of that genre to put a lens on some aspect of the relationship.

“It’s funny, because Ted Chiang is in this issue, and the Time Travel chapter was literally based on a lecture he gave us at Clarion about time travel, and the various ways that time travel can be used. I was thinking about the Novikov Self-Consistency Principle, which is a principle of time travel that Ted wrote about in ‘The Merchant at the Alchemist’s Gate’. I was literally thinking about Ted when starting that chapter, and all the things he has taught me through his work and teaching, and I was able to use that concept to interrogate a piece of this relationship.

“Each chapter uses these modes of interrogation, and then the chapters build into the story. Some of the chapters are what happened, just the events of the relationship. Some of them are events in my own past, or in my present, when I was trying to write the book. And then some of them are mini-essays reflecting research I was doing about the history of how we conceptualize things like domestic violence, how the queer community has talked historically about domestic violence, and also various ideas about gender and violence. These chapters use more academic or essayistic gestures.

“The result is this weird, hybrid memoir which, as I was writing, I honestly could not tell if I was pulling off or not. The whole time I was like, ‘Is this working?’ The pieces that are about the relationship itself are written in second person, so it uses this dissociative, or retrospective perspective, so I’m speaking to some past version of myself. The parts that are more essayistic, or contemporary, are in first person. The novel that I was thinking about when I made that choice was We the Animals by Justin Torres. It’s this really gorgeous novel about three brothers, and it’s mostly written in a plural first person, so ‘we’ instead of ‘I.’ Part of the way through the book, there’s this horrific thing that happens and the trauma is so intense that it ruptures the point of view, so it goes into second person, then third person, and then, eventually, first, and ends with this one brother peeled off from the others, and it’s just his ‘I’ voice. It’s so good! So gorgeous and so devastating. When I read it the first time I was sobbing, it was so intense. I really love the idea that something in the narrative could disrupt the PoV in a really essential way. It’s a formal device that creates this unbelievably devastating effect. So I was thinking about that novel when I decided to split the ‘I’ and the ‘You’ into these two discrete beings. There’s the Carmen that went off and lived her life and is getting interviewed right now by Locus magazine, and then there’s the Carmen who is trapped in this eternal hamster wheel of pain in the past, and doesn’t know what’s going on or how it’s going to unfold. It was an interesting device to further think about this relationship and its trauma. The whole time I was doing it I kept thinking, ‘Is this working?’ I finally got to the point where I realized it did work. But I was unsure for a not-insignificant amount of time, very concerned if it was even possible, what I was doing.

“What I’m talking about is this concept of the violence or the silence of the archive – which, to be very clear, is not my idea. The writer you should be reading if you’re interested in this concept is Saidiya Hartman, a brilliant writer and academic who wrote about the violence of the archive – in the context of narratives of enslaved people – in the essay that introduced this idea to me. The idea is that the archive – who determines what stories get told in the future, and who decides what stories are preserved and worth preserving – is, ultimately, a question of power and privilege, like everything else. Saidiya Hartmann makes the point that there are no contemporaneous accounts of enslaved peoples from the perspectives of those people. There’s just this huge hole in the narrative, and in history, and that is a violence. We did not preserve those stories from the people who experienced them, and now they’re gone and dead and their stories are lost to us forever.

“I learned about this idea really late in the process of writing the memoir. I had written a good chunk of the book already, and through a weird coincidence, my then-spouse met somebody who had studied archival science, and they recommended I read Hartman. I did, and it was mind-blowing. It gave a formal, academic backbone to these ideas that I was trying to articulate. Thank god for Saidiya Hartman. She gave me the answer. The fact that I went looking for a book that was going to speak to my own experience and could not find it – she gave me language to explain why that is a violent thing. So even though it came so late in the process of researching and writing the book, it really did unlock a lot of important stuff for me.

“I’m a formalist, I guess. I’m so interested in structure and form, way more than character. For some writers, character is the key for getting into the story, and I’m not like that. For me, it’s the shape, which is also partially why the short story is so useful, because you can experiment on the short story level in a way that’s harder in a novel. Not that you can’t do that on a novel level, but some formal experiments work for ten or 15 or 20 pages, but if you try to do that for 300 pages, the reader would not be along for the ride.

FOR MORE FROM THE FOCUS ON SHORT FICTION SPECIAL ISSUE…

Interview design by Francesca Myman.

Read the full interview in the November 2023 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.