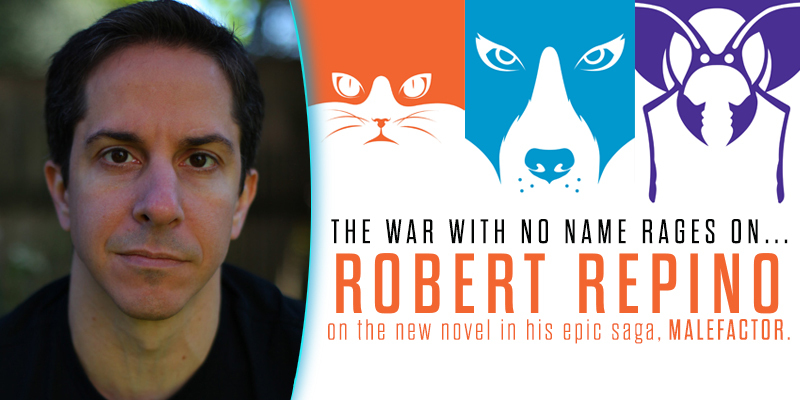

Spotlight on: Robert Repino

Your debut novel Mort(e) came out in 2015 and launched the War with No Name Series. Tell us about that book and the world it introduced.

The sales team likes to call it either “Animal Farm on steroids” or “Animal Farm with machine guns.” In short, the series is about a war between humans and sentient animals. In this world, a hyperintelligent queen of a globe-spanning ant colony has vowed to eradicate all humans. To do so, she uses a strange technology to “uplift” the surface animals, who become her soldiers. The animals suddenly find themselves walking upright, speaking, and thinking. While the pets are frightened and confused, the wild animals and the livestock have a bone to pick with humans, and are more than happy to accept the queen’s gift in exchange for vengeance.

Hijinks ensue. Humans are driven to near extinction. And the queen bestows the surface to the animals so they can create a new society.

In the aftermath, a housecat named Sebastian—who now goes by the name Mort(e)—goes on a quest to find Sheba, the dog that he loved before the world changed. Though traumatized by the terrible things he did to survive, he hopes for some sort of redemption. But things get complicated when he learns that Sheba is entangled with the dwindling human resistance, and could end up triggering an even deadlier phase of the war.

Your latest volume, Malefactor, is the fourth book in the series. Where does this book find your characters, and how have they changed since the series began?

Your latest volume, Malefactor, is the fourth book in the series. Where does this book find your characters, and how have they changed since the series began?

A mild spoiler for the series, which you’ve probably already guessed, is that Mort(e) finds Sheba. But this is not your typical happily-ever-after story. While Mort(e) wants to settle down on a farm, Sheba strikes out on her own, looking for the kind of adventure and self-discovery that Mort(e) has left behind. Like most uplifted animals, she chooses a new name, D’Arc, which is the title of the second novel in the series. By the end of that book, D’Arc agrees to go on an expedition to make contact with other communities of animals along the Atlantic coastline.

Malefactor explores the consequences of those decisions. Mort(e) is dying of an unexplained disease, the result of his contact with the ant colony. Meanwhile, D’Arc is lost at sea, and struggling to protect a litter of puppies. In order to survive, they both must use what they’ve learned from the other. Mort(e) must become more optimistic and empathetic, while D’Arc must become a soldier.

As the series draws to a close, do you feel that you or your writing has changed in any way over the course of writing the War with No Name?

It’s possible that I’ve simply exchanged one set of annoying tics for another. The first draft of the previous novel used the word “probably” 163 times, which my editor thought hilarious. For Malefactor, there was a particular sentence construction I leaned on too many times, and had to go through the subsequent drafts on a search-and-destroy mission.

Language aside, I think this novel is a little more sensitive and hopeful than the others. The antagonists this time around are wolves, and I focused a lot on their language and culture. Even though they do terrible things, I really wanted the reader to identify with them, to feel their fears, to hear their howls, to smell their fur. And whereas the previous books really focused on bashing the humans as a way of distinguishing them from the animals, this book more fully acknowledges that humans are animals, and as such they are subject to their instincts, superstitions, and tribalism.

You also write middle-grade novels. How does your approach differ when writing for adults versus for children?

My middle grade novel Spark and the League of Ursus has been sold as “Toy Story meets Stranger Things,” so it’s going for a whimsical but creepy tone. The main character is a teddy bear who fights monsters, which makes the story a slightly cartoonish version of War With No Name. After writing a series for adults for so many years, some violent and disturbing ideas crept into the book for children. On several occasions, my middle grade editor had to rein in the intensity for the sake of the audience. But, other than that, the style remains very similar. I was a history major in college, and I continue to work in that field in my day job, as an editor. So my writing leans more toward clarity than style.

For Spark, I also had to do some research into how much childhood has changed in the last generation. Among other things, I had to consider how young people engage with technology, how they’re taught about things like bullying, what kind of movies and TV shows they like. I’m not a parent, so I needed to ask around. For example, the human characters in my book are young filmmakers, and my editor suggested that they should have their own YouTube channel in which they show off their amateur movies. It was fun and kind of inspiring to see how the next generation is learning about hope and resilience in these weird times.

Tell us about your journey from being an aspiring writer to a published one.

Like all writers, my journey began with reading a lot and writing a lot. From an early age, I kept journals and wrote corny short stories and even cornier poems. I tried writing my first novel when I was 20. After about 50,000 words, I realized I had merely finished part one of a five-part(!) story, which was enough to get me to quit. I did not plan it out very well.

Over the next decade, I wrote three more novels, one of which was good enough to land an agent. But the agent couldn’t sell it, which was a demoralizing process. It’s one thing to be rejected, but it’s another feeling altogether when your agent sends a book into the void and you hear absolutely nothing back. (I can’t really blame the agent. The book was a speculative fiction story set in the Caribbean that was probably hard for readers to get.)

In the midst of that slow-moving failure, I basically said, fuck this, let’s write a fun book, and who cares if it sells? Around that same time, I had a strange dream about uplifted animals rampaging through the neighborhood where I grew up. About 18 months later, I completed the bonkers first draft of Mort(e), which I began sending out to new agents. Lucky for me, an editorial assistant pulled my book from the slush pile and showed it to the person who would eventually become my agent. But there was a catch: the agent said she would represent me only if I consented to a massive rewrite—and even then, she might still say no. Over the next nine months, we pulled the book apart and then put it back together twice. It was harrowing, but worth it. And it led to that first book deal, nearly fifteen years after my first attempt at a novel. So please, if you like writing, do not give u

Who are some of your literary influences? Were there books or authors whose work inspired your series?

I remember very vividly the first time I read The Left Hand of Darkness, over twenty years ago. Until then, I had loved science fiction and fantasy but had not really seen the full potential of it. But Left Hand shows how you can use all the cerebral elements of fiction to tell an exciting story, create fully-realized otherworldly characters, and say something that needs to be heard. One of my failed novels even tried to mimic Le Guin’s approach by inserting “primary source documents” into the narrative to help build the world.

In my day job, I edit scholarly articles on history and religious studies, and the bits of knowledge that I’ve gathered on social conflicts, theological disputes, and quirks of history have helped to fill in the details of all my fiction.

And yes, a book called Animal Farm may have influenced how I wrote this. One of the characters is a pig who chooses to be called Bonaparte. When asked why he didn’t go with Napoleon, he says that the name has already been taken. “Many times over,” he adds.

Robert Repino grew up in Drexel Hill, Pennsylvania. After serving in the Peace Corps (Grenada 2000–2002), he earned an M.F.A. in Creative Writing at Emerson College. His debut novel Mort(e), a science fiction story about a war between animals and humans, was published by Soho Press in 2015. Mort(e) is the first book in the War With No Name Series, which includes D’Arc and Culdesac. His first novel for middle-grade readers is Spark and the League of Ursus, part of a two-book series published by Quirk Books. His novella Leap High Yahoo was published as an Amazon Kindle Single.

Repino is the pitcher for the Oxford University Press softball team and quarterback for the flag football team, but his business card says that he’s an Editor. He also occasionally teaches for Gotham Writers Workshop.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.