The Casual Embrace by Paul Kincaid

Part way through The Silence by Don DeLillo (Picador) I came across a passage that resonated with me more that it perhaps might have done in other circumstances. One of the characters, in one of those archetypal DeLillo conversations that have the dispiriting and disconnecting feel of overlapping monologues, asks: “Is this the casual embrace that marks the fall of world civilization?”

DeLillo’s novella was written before the pandemic that has had us all spending the year in that casual embrace, but for me it captures perfectly the affect of that year: the sense of isolation, the way that everything is turned so resolutely inwards that any world out there disappears from our ken. And in a year in which our social life has been conducted digitally, our cultural life has been spent not in cinemas and theatres, in concert halls and galleries, but in front of a television screen, then the loss of that digital connection, the blankness of that television screen, is especially chilling. The five characters in this story, as they become increasingly detached from each other, are on the verge of a catastrophe, but because they are unable to grasp what is happening, intellectually or emotionally, they have no way of understanding the scale of the catastrophe they face.

DeLillo’s book is not the first to deal with a digital catastrophe (I recall Waubgeshig Rice’s excellent Moon of the Crusted Snow a year or two back), and it won’t be the last (I haven’t read it yet, but Jonathan Lethem’s The Arrest seems to touch on the same idea), but DeLillo’s chill, minimal, distancing prose seems perfectly suited to the subject.

DeLillo’s book is not the first to deal with a digital catastrophe (I recall Waubgeshig Rice’s excellent Moon of the Crusted Snow a year or two back), and it won’t be the last (I haven’t read it yet, but Jonathan Lethem’s The Arrest seems to touch on the same idea), but DeLillo’s chill, minimal, distancing prose seems perfectly suited to the subject.

While most of us have spent the year in a sort of self-imposed internal exile, venturing out only when necessary, masked and wary, the myth has gathered ground that it has been a great year for reading. But the truth is not as simple as that. I have read a bunch of highly praised, even award-winning science fiction novels this year only to toss them aside, often unfinished, because they offered no genuine satisfactions. In another year, when my mind was not so distracted by external threats or by the increasingly obvious madness and incompetence of our political leaders, might these books have spoken more directly to me? Possibly, but too many of them seemed overly reliant on the familiar, the cliched, dressed in the unconvincing costume of a false radicalism, when what my mind was crying out for was something genuinely daring, genuinely new, genuinely radical.

Some books did break through the ennui of our disaffecting times, of course. For some reason, non-fiction did so reliably. I particularly enjoyed Utopia and the Contemporary British Novel by Caroline Edwards (Cambridge) and H.G. Wells: A Literary Life by Adam Roberts (Palgrave); but for me the standout book of the year was Inventing Tomorrow: H.G. Wells and the Twentieth Century by Sarah Cole (Columbia), which does offer a radical and convincing new account of Wells’s work.

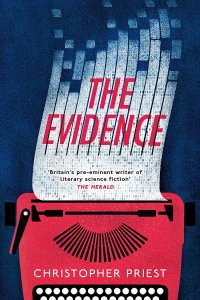

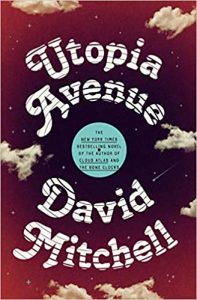

Fiction, on the other hand, was more problematic. I enjoyed, for instance, Utopia Avenue by David Mitchell (Sceptre) for his uncompromising account of the 1960s music scene, but not so much for the ongoing fantasy that has connected all of his novels. And while The Evidence by Christopher Priest (Gollancz) was an entertaining Dream Archipelago novel, it seemed very much an undemanding read, until I came to write a review of the book and found myself uncovering interconnections and complexities that hadn’t been obvious while I was actually reading the book.

Fiction, on the other hand, was more problematic. I enjoyed, for instance, Utopia Avenue by David Mitchell (Sceptre) for his uncompromising account of the 1960s music scene, but not so much for the ongoing fantasy that has connected all of his novels. And while The Evidence by Christopher Priest (Gollancz) was an entertaining Dream Archipelago novel, it seemed very much an undemanding read, until I came to write a review of the book and found myself uncovering interconnections and complexities that hadn’t been obvious while I was actually reading the book.

There were, however, a couple of books that really sang out their freshness and importance even in a year that seemed otherwise somewhat lacklustre. My belated discovery of the year was the extraordinary short fiction of Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky, in particular his collection Memories of the Future (NYRB). I chanced upon this because of my interest in Siri Hustvedt’s wonderful mainstream novel, Memories of the Future, but Krzhizhanovsky’s stories are entirely different. His work dates mostly from the 1920s and 1930s, but were almost all unpublished in the Soviet Union during his lifetime. They only began to appear in the Soviet Union many years after his death in 1950, and it is really only in this century that they have started to be translated into English. (This particular collection, wonderfully translated by Joanne Turnbull, first appeared in the US about 15 years ago.) The stories are vivid satires of the Soviet system, but expressed through an extraordinary grasp of the fantastic. A one-room Moscow apartment begins to expand so much that the hapless occupant becomes lost within it; a traveller takes the wrong train and ends up in the place where nightmares are manufactured; a time traveller gets a glimpse of the future only to find it identical to his present. I hope I am simply late to this particular party and everyone already knows about the startling stories of Krzhizhanovsky but, if not, you owe it to yourself to read these stories.

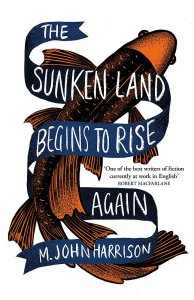

As for the novel of 2020, there really is only one contender: The Sunken Land Begins to Rise Again by M. John Harrison (Gollancz). In retrospect, I can see a kinship between Harrison’s novel and Krzhizhanovsky’s stories. Both start from a basis of well-observed and vividly recreated reality. Into this reality something strange emerges, but it is not seen as unusual by the characters within the fiction. In the end, the fantastic has little if any material effect upon the world as viewed by the protagonists. In Harrison’s novel, this irruption of the weird takes the form of images of a submarine world starting to superimpose themselves upon everyday reality: greenish-skinned figures emerging, people submerging themselves entirely in shallow pools, water-stained copies of Charles Kingsley’s The Water Babies being passed from hand to hand. But the two central characters, around whom these watery effects seem to congregate, are too caught up in their own worries to really notice. One is a middle-aged man trying to start his life over again after a breakdown, who finds makeweight work with a curious enterprise whose owner runs a blog devoted to stories of a water world; the other a middle-aged woman trying to remake her late mother’s home amid the waterlogged streets of a midland town. Each sees the repeated watery images as an externalization of their own neuroses, so that if, in the end, the sunken land is indeed rising again, it is not something that can ever be seen with any certainty.

As for the novel of 2020, there really is only one contender: The Sunken Land Begins to Rise Again by M. John Harrison (Gollancz). In retrospect, I can see a kinship between Harrison’s novel and Krzhizhanovsky’s stories. Both start from a basis of well-observed and vividly recreated reality. Into this reality something strange emerges, but it is not seen as unusual by the characters within the fiction. In the end, the fantastic has little if any material effect upon the world as viewed by the protagonists. In Harrison’s novel, this irruption of the weird takes the form of images of a submarine world starting to superimpose themselves upon everyday reality: greenish-skinned figures emerging, people submerging themselves entirely in shallow pools, water-stained copies of Charles Kingsley’s The Water Babies being passed from hand to hand. But the two central characters, around whom these watery effects seem to congregate, are too caught up in their own worries to really notice. One is a middle-aged man trying to start his life over again after a breakdown, who finds makeweight work with a curious enterprise whose owner runs a blog devoted to stories of a water world; the other a middle-aged woman trying to remake her late mother’s home amid the waterlogged streets of a midland town. Each sees the repeated watery images as an externalization of their own neuroses, so that if, in the end, the sunken land is indeed rising again, it is not something that can ever be seen with any certainty.

Harrison’s novel is, to a degree, a Brexit novel, a reflection of despair at the world being changed by unfeeling forces beyond our control. But it was written long before coronavirus became a devastating factor in our everyday lives, as were DeLillo’s novella and, of course, Krzhizhanovsky’s stories. Yet, all three books seem to speak sharply and precisely to the moment. All three would be remarkable books in any circumstances, but the circumstances have given them an extra and devastating resonance.

Paul Kincaid has published two collections of essays and reviews, What It Is We Do When We Read Science Fiction (2008) and Call and Response (2014). His most recent book is Iain M. Banks (2017). He has been awarded the Clareson Award from the SFRA and the BSFA Non-Fiction Award.

This review and more like it in the February 2021 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.