SF in Brazil, 2020 by Roberto Causo

Under a denialist president, Brazil has suffered dearly with the COVID-19 pandemics. As I write this, the official death-toll is just over 200,000, and there’s no town or city in the country free of cases. Most economy sectors have been impacted – yet, surprisingly, translated science fiction novels became a sure-footed presence in the bestselling lists. These works are mostly dystopian novels such as The Handmaid’s Tale & The Testaments, Fahrenheit 451, Nineteen Eighty-Four & Animal Farm, Brave New World, alongside Albert Camus’s La Peste (The Plague) and other books that clearly show Brazilians trying to figure out their authoritarian, conservative, bleak times.

Under a denialist president, Brazil has suffered dearly with the COVID-19 pandemics. As I write this, the official death-toll is just over 200,000, and there’s no town or city in the country free of cases. Most economy sectors have been impacted – yet, surprisingly, translated science fiction novels became a sure-footed presence in the bestselling lists. These works are mostly dystopian novels such as The Handmaid’s Tale & The Testaments, Fahrenheit 451, Nineteen Eighty-Four & Animal Farm, Brave New World, alongside Albert Camus’s La Peste (The Plague) and other books that clearly show Brazilians trying to figure out their authoritarian, conservative, bleak times.

Publishing companies rushed to ride that wave with new translations of Orwell’s works, since he went into the public domain in 2020. Editora Aleph released both of Orwell’s classics with pop-comics artcovers done by Brazilian graphic designer Butcher Billy, and powerful Companhia das Letras released the books as local Penguin Classic editions, in addition to a hip hardcover edition. The same Cia das Letras produced and released a graphic-novel adaptation of Nineteen Eighty-Four done by artist Fido Nesti. Finally, Editora Pandorga, which has a line of luxury-bargain books, announced a slipcase with both classics in hardcover for January 2012.

We also saw other bestselling books less related to the current turmoil, like Stephen King’s It, Neil Gaiman’s Norse Mythology, Dean Koontz’s The Eyes of Darkness, Stephanie Meyer’s Midnight Sun, and several story collections and boxes of works by Edgar Allan Poe and H.P. Lovecraft.

AN UNEXPECTED LOCAL TREND

A curious, inspiring trend gathered momentum in the past two years: the coming back of Brazilian SF and horror works from the past. It has had as forerunners Braulio Tavares’s anthology Páginas do Futuro: Contos Brasileiros de Ficção Científica (Pages of the Future: Brazilian SF Short Stories; 2011); Nelson de Oliveira’s huge, ambitious and multiple award-winning Fractais Tropicais: O Melhor da Ficção Científica Brasileira (Tropical Fractais: The Best of Brazilian SF; 2018); and my anthology series Os Melhores Contos Brasileiros de Ficção Científica (Best Brazilian SF Short Stories; 2007), Os Melhores Contos Brasileiros de Ficção Científica: Fronteiras (Borders; 2009), and As Melhores Novelas Brasileiras de Ficção Científica (Best Brazilian SF Novellas; 2011).

A curious, inspiring trend gathered momentum in the past two years: the coming back of Brazilian SF and horror works from the past. It has had as forerunners Braulio Tavares’s anthology Páginas do Futuro: Contos Brasileiros de Ficção Científica (Pages of the Future: Brazilian SF Short Stories; 2011); Nelson de Oliveira’s huge, ambitious and multiple award-winning Fractais Tropicais: O Melhor da Ficção Científica Brasileira (Tropical Fractais: The Best of Brazilian SF; 2018); and my anthology series Os Melhores Contos Brasileiros de Ficção Científica (Best Brazilian SF Short Stories; 2007), Os Melhores Contos Brasileiros de Ficção Científica: Fronteiras (Borders; 2009), and As Melhores Novelas Brasileiras de Ficção Científica (Best Brazilian SF Novellas; 2011).

In the last months of 2019, Plutão Livros released ebook editions of Jeronymo Monteiros’s 1947 classic novel of time travel and future war 3 Meses no Século 81 (3 Months in the 81st Century) and Dinah Silveira de Queiroz’s groundbreaking 1960 story collection Eles Herdarão a Terra (They Shall Inherit the Earth) – both republished for the first time. They appeared at Plutão’s line Ziguezague, which included Finisia Fideli’s 1994 time-travel novelette O Ovo do Tempo (The Time Egg) and my 1991 awarded novelette Patrulha para o Desconhecido (Patrol to the Unknown), also as ebooks.

In 2020, Ziguezague, which has a knowledgeable series introduction by Ana Rüsche, shifted to previously unpublished works, yet publisher André Caniato told me: “I think that the trend is real. I’d very much like to know up to what point this was really driven or encouraged by Plutão’s activities, but it has even happened that people publishing a work I wanted to publish for years. Of course, I hope this enthusiasm will continue.”

Other major works of the past were Emília Freitas’s pioneering feminist novel of abused women and slaves rescued by a secret society of female paladins A Rainha do Ignoto (Queen of the Unknown; 1899), and Coelho Netto’s Gothic novel of transsexuality Esfinge (Sphinx; 1908). The first appeared through Editora Wish, with a scholarly preface by Dr. Alexander Meireles da Silva, an expert on 19th-century Brazilian SF who investigates Freitas’s novel both as SF and fantasy, and an afterword by writer Adrianna Alberti. Coelho Netto’s book has had a flurry of editions, from Editora Raio (as an ebook), Editora Vermelho Marinho, and finally Editora Legatus – this one also prefaced by Meireles da Silva and with an afterword by Dr. M. Elizabeth Ginway of University of Florida and author of Brazilian Science Fiction (2004). Both the Wish and the Legatus editions resulted from crowdfunding campaigns. Legatus is working now at an effort to bring back Menotti del Picchia’s 1930 A Filha do Inca (The Inca’s Daughter) in 2021, a lost-world novel also seen in France.

Brazil’s pulp writers (born in 1930), strongly linked to horror fiction in literature, cinema, and comics, has his own republication program with the Coleção R.F. Lucchetti, assembled by local small press Editora Corvo. It begun in 2014 and brought back more than 12 books already – among them 7 Ventres para o Demônio (7 Wombs for the Demon; 1974) and A Filha de Drácula (Dracula’s Daughter; 2017), an original, never filmed screenplay. Precociously starting to write in the 1940s for local pulp magazines, Lucchetti authored more than 1,500 books and, in the 1960s, became a screenwriter for the recently deceased innovative moviemaker José Mojica Marins, “Coffin Joe,” as he was known in the US and Europe.

Brazil’s pulp writers (born in 1930), strongly linked to horror fiction in literature, cinema, and comics, has his own republication program with the Coleção R.F. Lucchetti, assembled by local small press Editora Corvo. It begun in 2014 and brought back more than 12 books already – among them 7 Ventres para o Demônio (7 Wombs for the Demon; 1974) and A Filha de Drácula (Dracula’s Daughter; 2017), an original, never filmed screenplay. Precociously starting to write in the 1940s for local pulp magazines, Lucchetti authored more than 1,500 books and, in the 1960s, became a screenwriter for the recently deceased innovative moviemaker José Mojica Marins, “Coffin Joe,” as he was known in the US and Europe.

Anthologies have also been recovering old works of Brazilian horror. They tread the path opened by a consolidated trend of historical anthologies with stories in public domain and released by medium and large publishing companies since the end of the 20th century. This recovery effort is also related to the emergence of horror/Gothic studies in Brazilian universities.

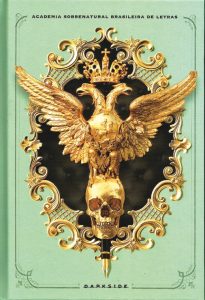

Thus we’ve had Páginas Perversas: Narrativas Brasileiras Esquecidas (Wicked Pages: Forgotten Brazilian Narratives; 2017), edited by Maria Cristina Batalha, Júlio França & Daniel Augusto P. Silva for Appris Editora, all scholars; Contos Clássicos de Terror (Classic Terror Tales; 2018), edited by Julho Jeha, with Brazilian (Machado de Assis and Lygia Fagundes Telles, among them) and foreign authors; and Academia Sobrenatural Brasileira de Letras (The Supernatural Brazilian Academy of Letters; 2019), edited by Romeu Martins, with horror and supernatural stories of 19th-century authors who belonged to the Brazilian Academy of Letters – in a beautiful hardcover edition through DarkSide Books.

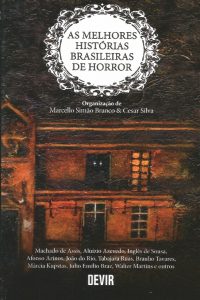

Yet the most important anthology should be As Melhores Histórias Brasileiras de Horror (Best Brazilian Horror Stories; 2019), edited by Marcello Simão Branco & Cesar Silva, gathering stories from the 1800s to 2014. We find there works like Tabajara Ruas’s novella O Fascínio (The Fascination; 1997), and Braulio Tavares’s short story “Bradador” (Screamer; 2014), along with several others by Machado de Assis, Aluísio Azevedo, Inglês de Sousa, Afonso Arinos, Gastão Cruls, João do Rio, Márcia Kupstas, Júlio Emílio Braz, Carlos Orsi, Walter Martins, and others. Published by Devir Brasil, a company that in 2020 ceased to consider new works of fiction, it is not restricted to texts in public domain. Branco’s lengthy introduction provides an extensive and deep picture of the history and characteristics of horror fiction in Brazil.

Of course, most of this is at the fringe of genre publishing in Brazil, which is dominated by translations, and we shouldn’t expect it to be picked up by larger and more influential publishers.

INTENSE AWARD SEASON

The year of 2020 witnessed an especially intense batch of awards, beginning with the already successful Odyssey of Fantastic Literature Award, sponsored by an event of the same name set in Porto Alegre, in the Brazilian South. Nikelen Witter’s steampunk novel Viajantes do Abismo (Travellers of the Abyss) won Best Long Narrative in Science Fiction; Carol Chiovatto’s YA novel Porém Bruxa (Witch Though) won Best Long Narrative in Fantasy; Júlio Ricardo da Rosa’s novel O Inverno do Vampiro (Winter of the Vampire) won Best Long Narrative in Horror. Ana Rüsche’s remarkable literary novella A Telepatia São os Outros (Telepathy Are the Others) won Best Short Narrative in Science Fiction; Cristina Pezel’s story about goblins “Jeremejevite” won Best Short Narrative in Fantasy; and Márcio Benjamin’s “Sete Cordas” (Seven Strings) won Best Short Narrative in Horror. Finally, Otávio Definski’s Terra Vazia (Empty Land) won Best Long Narrative for Children and Teen Readers. The results were given in May.

The year of 2020 witnessed an especially intense batch of awards, beginning with the already successful Odyssey of Fantastic Literature Award, sponsored by an event of the same name set in Porto Alegre, in the Brazilian South. Nikelen Witter’s steampunk novel Viajantes do Abismo (Travellers of the Abyss) won Best Long Narrative in Science Fiction; Carol Chiovatto’s YA novel Porém Bruxa (Witch Though) won Best Long Narrative in Fantasy; Júlio Ricardo da Rosa’s novel O Inverno do Vampiro (Winter of the Vampire) won Best Long Narrative in Horror. Ana Rüsche’s remarkable literary novella A Telepatia São os Outros (Telepathy Are the Others) won Best Short Narrative in Science Fiction; Cristina Pezel’s story about goblins “Jeremejevite” won Best Short Narrative in Fantasy; and Márcio Benjamin’s “Sete Cordas” (Seven Strings) won Best Short Narrative in Horror. Finally, Otávio Definski’s Terra Vazia (Empty Land) won Best Long Narrative for Children and Teen Readers. The results were given in May.

This year’s Leblanc Awards for Animation, Sequential Art and Fantastic Literature went to Fábio Barreto’s contemporary SF thriller set in the US, Snowglobe, an ebook, in the Best Novel category. Best Anthology/Collection went to Duendes: Contos Sombrios de Reinos Invisíveis (Goblins: Dark Tales of Invisible Kingdoms), edited by Ana Lúcia Merege, a multi-award winner editor, for Editora Draco. The results were given in June.

Our oldest award around is the Argos Awards for Fantastic Literature, given by fan-club Science Fiction Readers’ Club. Best Novel went to Gilson Cunha’s comical SF adventure Onde Kombi Alguma Jamais Esteve (Where No Kombi Has Gone Before). Cunha also won Best Short Story with “A Mulher que Chora” (“Tide of Tears” in the English ebook version), with a more serious literary approach, about a mysterious woman found in the waters of Antarctica. About his double winning, Cunha told me: “I was surprised and touched, even more considering I’m independent and don’t have the support of publishers and literary agencies. It has motivated me tremendously in keeping telling those stories (in the case of the Onde Kombi Alguma Jamais Esteve‘s universe) and others. I’m indebted to the readers.”

Best Anthology/Collection went for Cyberpunk: Registros Recuperados de Futuros Proibidos (Recovered Records of Forbidden Futures), edited by Cirilo S. Lemos & Erick Cardoso, for Editora Draco. Results were given at the end of November.

This year’s award season was boosted by huge interest in the new category of the Jabuti Award, the most important literary award in Brazil (analogous to the National Book Award in the US): “Best Novel of Entertainment” – which is a bit hard to swallow, since “entertainment literature” in Brazil is “commercial literature.” Obviously, some pressure to honor books of sales appeal is behind the initiative. It is then perhaps paradoxical that the category was dominated by small presses with no significant share of the market, such as Jambô Editora, Monomito Editorial (with two nominees), Patuá Editora, and Avec Editora, mostly with speculative fiction books. Clearly, big publishers are focused on translations, and only a couple of the biggies had nominees: Cia das Letras and Intrínseca.

The winner was Uma Mulher no Escuro (A Woman in the Dark) by Raphael Montes through the powerful and prestigious Cia das Letras, which sort of reestablished normalcy, yet small presses included in this first edition of the category should expect a raise in their status.

Ana Rüsche, whose A Telepatia São os Outros was a runner-up for most awards this year, told me winning the Odyssey Award is “a national recognition from the Brazilian SF/F community. If the Jabuti Award is more popular (even my neighbors have congratulated me for being a finalist), the Odyssey Award is a specific one, given by a jury that follows the market book by book and therefore very dear.”

The Machado Prize was not an award but a contest for original works that would kickstart the presence of local authors in the appreciated DarkSide Books. The prize also stirred things up in the field, with about five thousand works submitted in several categories, according to DarkSide. The winner in the novel category was Bruno Ribeiro’s dystopia Porco de Raça (Pure-bred Pig, or The Pig Has Guts) about the racial issue (Ribeiro is an Afro-Brazilian man). In an interview made by the DarkSide staff, he said: “DarkSide readers may expect a provocative work, both in language and plot, dealing with urgent themes such as racial prejudice and inequality, in a surreal, scary and transgressive manner, with no softening to anyone, quite the opposite. The book is also about me and my people, the racist acts we have suffered and those traumas that insist on remaining.” Other works in comics and audiovisual projects have also had Afro-Brazilians as winners in that contest.

Famous Brazilian playwright Nelson Rodrigues stated that “all unanimities are dumb,” now a popular saying in Brazil. This 2020 award season has shown no overlapping of winners, awarding works from different trends and approaches.

OTHER RELEASES AND TRENDS

New works keep coming around and the new buzzword in the field is indeed “Afrofuturism.” A couple of Afrofuturist authors, Lu Ain-Zaila and Waldson Souza, are in the original anthology Vislumbres de um Futuro Amargo (Glimpses of a Bitter Future), edited by Gabriela Colicigno & Damaris Barradas for Colicigno’s Agência Magh, a literary agency. The book also brings stories by Lady Sybylla, Cláudia Fusco, Anna Martino, and Roberto Fideli. Fusco’s work is a delicate narrative about a robot-maid and her burden, a girl, in a story that would fit well in Strange Horizon or other digital magazines of today, while Martino’s is an ironic narrative about family and relationships set in the far future that would fit nicely in Asimov’s. Fideli’s, on the other hand, is a hard SF adventure that skillfully defies expectations – Magh has also published Fideli’s first ebook, A Bicicleta (The Bicycle; 2020), another SF novelette.

New works keep coming around and the new buzzword in the field is indeed “Afrofuturism.” A couple of Afrofuturist authors, Lu Ain-Zaila and Waldson Souza, are in the original anthology Vislumbres de um Futuro Amargo (Glimpses of a Bitter Future), edited by Gabriela Colicigno & Damaris Barradas for Colicigno’s Agência Magh, a literary agency. The book also brings stories by Lady Sybylla, Cláudia Fusco, Anna Martino, and Roberto Fideli. Fusco’s work is a delicate narrative about a robot-maid and her burden, a girl, in a story that would fit well in Strange Horizon or other digital magazines of today, while Martino’s is an ironic narrative about family and relationships set in the far future that would fit nicely in Asimov’s. Fideli’s, on the other hand, is a hard SF adventure that skillfully defies expectations – Magh has also published Fideli’s first ebook, A Bicicleta (The Bicycle; 2020), another SF novelette.

After appearing in the book, Ain-Zaila became a juror for the Odyssey Awards. She is the author of the 2019 story collection Sankofia, an ebook, and of the “cyberfunk” novella Ìségún (2019), a Monomito title. Souza is now editing an Afrofuturist anthology for Plutão Livros.

Maybe registering the Afrofuturist buzz, and the newly revealed potential for award distinction in the field, Intrínseca announced new work by veteran Afro-Brazilian authors Jim Anotsu and Fábio Kabral – an early name associated with Afrofuturism who just signed to write for Intrínseca a fantasy epic based on Afro-Brazilian religions.

A NEW MAGAZINE MOMENT?

Magazine publishing seems to have gathered a new momentum in 2020, even if it is seldom above amateur efforts. The longest running title that we have ought to be Somnium, founded in 1986 by R.C. Nascimento as the clubzine of the Science Fiction Readers’ Club. It failed to produce a new edition in 2020 (in PDF and e-pub). The other bad news is that another veteran electronic magazine, Rodrigo van Kampen’s Trasgo, founded in 2014, went into hiatus in September after publishing 138 stories, including translations previously seen in the Strange Horizons special Brazilian edition in 2019. On the other hand, Jana Bianchi’s Mafagafo, founded in 2018, is still going strong, publishing SF and fantasy novelettes. Literomancia is edited by Luana Nicolaiewsky and combines stories and essays, existing since 2019 and freely distributed. Edited by Diogo Ramos, A Taverna is also an electronic magazine, with three issues available as an Amazon Kindle ebook since 2019 and presenting covers with great art. This is the only known mag that’s a paid market.

Magazine publishing seems to have gathered a new momentum in 2020, even if it is seldom above amateur efforts. The longest running title that we have ought to be Somnium, founded in 1986 by R.C. Nascimento as the clubzine of the Science Fiction Readers’ Club. It failed to produce a new edition in 2020 (in PDF and e-pub). The other bad news is that another veteran electronic magazine, Rodrigo van Kampen’s Trasgo, founded in 2014, went into hiatus in September after publishing 138 stories, including translations previously seen in the Strange Horizons special Brazilian edition in 2019. On the other hand, Jana Bianchi’s Mafagafo, founded in 2018, is still going strong, publishing SF and fantasy novelettes. Literomancia is edited by Luana Nicolaiewsky and combines stories and essays, existing since 2019 and freely distributed. Edited by Diogo Ramos, A Taverna is also an electronic magazine, with three issues available as an Amazon Kindle ebook since 2019 and presenting covers with great art. This is the only known mag that’s a paid market.

Writer Gabriel Boz started his magazine of short-shorts GBoz, mostly with his own works. Edited by Jean Gabriel Álamo, Revista Literatura Fantástica is another title available on Amazon but proclaiming itself a pulp magazine, with scores of contributors in its first issue and an introduction by Meireles da Silva on the history of pulp.

Appearing in December, Histórias Extraordinárias, edited by Marcus Garrett & Mario Cavalcanti and published by Editora Mundo, is a paper magazine with good cover art by Andres Ramos and stories by Garrett, Cavalcanti, and Paolo Pugno – whose debut happened in 1982. The magazine intends to be a quarterly.

My own promotional magazine in PDF, Universo GalAxis Anual 2019, edited by Taira Yuji, focused on my GalAxis Universe and space opera in general (<universogalaxis.com.br/revista/anual2019/>).

–Roberto Causo

This report and more like it in the February 2021 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.