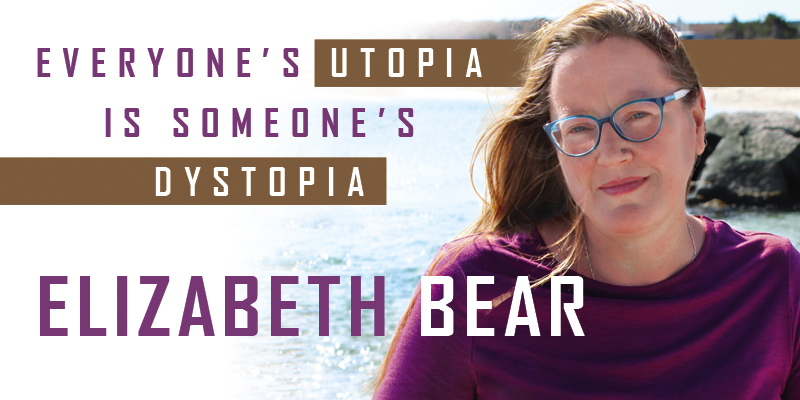

Elizabeth Bear: Everyone’s Utopia Is Someone’s Dystopia

Sarah Bear Elizabeth Wishnevsky was born September 22, 1971, in Hartford CT. She attended the University of Connecticut, where she studied English and anthropology, though she did not take a degree. She has worked as a technical writer, stable hand, reporter, and in assorted office jobs, and has been writing full-time since 2006. She married Christopher Kindred in 2000, divorcing in 2007. She became involved with fantasy writer and firefighter Scott Lynch in 2011, and they married in 2016.

From 2007 to 2014 Bear collaborated on web serial Shadow Unit, a supernatural FBI procedural, with Emma Bull, Sarah Monette, Will Shetterly, Leah Bobet, C.L. Polk, Amanda Downum, Steven Brust, and Holly Black. Until 2015 she co-hosted Hugo Award-winning podcast SF Squeecast. Bear won the Campbell Award for Best New Writer in 2005, and has taught at writing workshops Viable Paradise, Clarion, and Clarion West.

Her newest work is Ancestral Night (2019), launching the White Space series. Book two, Machine, is forthcoming in October.

She lives in Western Massachusetts with her husband.

Excerpts from the interview:

“It felt awfully good to come back to science fiction with Ancestral Night, though I use a lot of the same strategies to write science fiction and fantasy. They both tend to have a strong strain of cultural anthropology running through them – I’m interested in how people interact with their cultures and how cultures shape personality. I’m very interested in how relationships and expectations shape how people interact with their communities and their environments, and in navigating that whole expectation-versus-personal-freedom-versus-life-goals thing. In both SF and fantasy, I tend to have a certain amount of conflict on those levels. I mostly wandered away from science fiction because I couldn’t sell it for a while. The market was sort of ‘fantasy or nothing,’ especially if you were a woman. What’s really interesting with Ancestral Night is that I sold it in 2014, and in 2015 I had some chronic health issues, which I blogged about if anybody really wants to know, and I requested an extension on the book. Then the editor I sold it to left Gollancz, and the 2016 election happened, and I felt like I couldn’t write the book I had started writing – I had to start over from scratch. The original book was a much more multi-point-of-view, sweeping scale, political space opera, something like M.J. Locke’s Up Against It, or the Expanse books. What I wound up doing was having to pull way back and tell this very personal story about a person navigating her own life experiences and the fallibility of memory. Then I realized it was in the same universe, although not in any way a sequel to, the Jacob’s Ladder books, which were actually the last science fiction novels I wrote. They sold okay – they didn’t do blockbuster numbers out of the gate, but they’ve been consistently slow burn. That is Dust, Chill, and Grail in the US, called Pinion, Sanction, and Cleave in the UK. They’ve been out there for ten years or more at this point, quietly selling, more and more people reading them. I get fan mail – word-of-mouth on them must be pretty good. They’re weird, like gothic Arthuriana in space. I pitched them to Anne Groell, my editor, as ‘Upstairs:Downstairs::Amber:Gormenghast, in SPAAAAAAAAAACE!’ They’re pretty inside-baseball books I guess, but they seem to have found their audience.

“When I realized that the deep backstory for those books was the same as the deep backstory for Ancestral Night, that made the world I was writing make a lot more sense. I had gone into it thinking, ‘Oh, people either write space opera in which there are republics and empires and the system of government hasn’t changed in 6,000 years, or they write space opera where there is fully automated luxury gay space communism.’ But there’s no real look at how the latter works or what the drawbacks of the system are, it’s usually, ‘This is a post-scarcity economy and it just works.’ There’s nothing wrong with that. Or you get the C.J. Cherryh sort of end-stage-capitalism-in-space thing. There’s some Andre Norton influence to my approach, definitely. I wound up talking about strategic decision-making to a bunch of people who do futurism, and about how we can govern better, and different forms of government that still manage to be humane and democratic, without the end-stage capitalism problems – but also without relying on that ‘the system just works’ ethos. I got really interested in the economics of a post-scarcity universe, which becomes a major plot engine driving the book.

“I don’t go looking for reviews necessarily, but stuff filters in through the Twitters, people tag you, and there are three groups of readers and critics who hate Ancestral Night a lot. There are the ones who think it’s bleak dystopianism about mind control (with cats), and the ones who think it’s utopian propaganda, and the ones who really, really don’t like long, philosophical, first-person inserts from a female character. It’s fascinating. I’m very interested in the idea that everybody’s utopia is somebody else’s dystopia, and vice versa. I think of this book as having an argument with itself about social control versus personal control. Also, we’ve really experienced a sea change as a culture – I mean world culture, human society – in our ability to manage our mental health in the last 30 years. We’re making great strides in our understanding of neurology, psychology, brain chemistry, how mental illness works, and how to treat things that were previously thought of as completely intractable, like severe PTSD and bipolar disorder. That forces a reexamination of books like Brave New World, where psychoactive medication is entirely seen as a means of social control. The reason that Robert Anton Wilson’s Illuminatus books get a shoutout in Ancestral Night is because that’s a set of books about, among other things, using psychoactive medications to break social control. I feel like we really need to reexamine all of those ideas and tropes in the light of what we now know about the technology. Our idea of medicating mental illness has gone from ‘Mother’s Little Helper’ and sedating people who can’t deal with the rigors of their daily lives or the social pressures arrayed against them and sedating people so they’ll fall in line with social control, to the realization that, appropriately managed, psych meds are good for mental health. They can make people less reactive and more forceful and more capable, and more able to fix things rather than retreating into depression or anxiety. That’s one of the things Ancestral Night is very strongly about.

“I had to go back and start the book over, and then start over with a new editor – Ann Leckie happened, and suddenly there was a marketing push behind the book, because space opera by women is now the hot new thing, or one of the hot new things. The real novum in this book is the governmental structures, and the idea that one of the things that will help us to advance as a society is fixing some of our atavistic behaviors. Rebecca Solnit’s Paradise Built in Hell is a book about how people come together in disasters – maybe it would be possible to put ourselves intentionally into that state of community-mindedness and stay there, even when the disaster has passed. That’s the deep backstory of the book – it’s how they managed to not destroy the planet. Basically, all the tech bros left, and the people who were left behind on Earth with limited economic means were like, ‘Well, we’ve been left on this planet to die. I don’t think that’s what I want to do with my life – what if we fix things instead?’ They started by fixing themselves. That’s something I really admire about Connie Willis’s Doomsday Book, which is very much about the different people’s means of dealing with catastrophe. You have the people who improve themselves and the lives of the people around them even while the world is literally ending. So the deep backstory in Ancestral Night is this idea that here were a bunch of people staring at catastrophe and an extinction event, who said, ‘Okay, the first thing we have to do is fix people. We all need to be grownups now. There’s no other option. So how do we rewire our brains to make ourselves grownups?’ Taking responsibility for things – I believe the technical term is ‘owning your shit.'”

Interview design by Stephen H. Segal. Photo by Liza Groen Trombi.

Read the full interview in the May 2020 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.