Nexus by Paul Kincaid

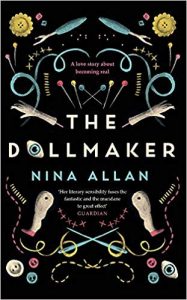

Every so often you come across a book that seems to act as a nexus, drawing other recently read books into an unexpected pattern, even though they otherwise seem completely unconnected. For me, this year, that nexus was The Dollmaker by Nina Allan (riverrun). One of the two central characters is a dwarf who becomes an expert and sought-after maker of dolls, which immediately called to mind Little by Edward Carey (Aardvark Bureau, 2018), whose central character is a dwarf in pre-revolutionary France who becomes an expert maker of waxworks and who will go on to become Madame Tussaud. The other central character in The Dollmaker lives in a remote mental hospital turned halfway house whose curious, barely functional community reminds me of the similar home and its inhabitants at the heart of Sarah Perry’s first novel, After Me Comes the Flood (Serpent’s Tail, 2014). The narrative that ever-so-slowly brings these two characters together is constantly interrupted by oddly disturbing stories supposedly written by a Polish dollmaker and wartime refugee, Ewa Chaplin, and I’m sure it wasn’t the coincidence of the title that reminded me of the oddly disturbing stories in The Doll’s Alphabet by Camilla Grudova (Fitzcarraldo, 2017).

What fascinates me about The Dollmaker, as it did with Nina Allan’s previous novel, The Rift, is that it is impossible to say whether or not we are meant to take it as a work of straightforward realistic fiction. Anything overtly weird or fantastic is restricted to the interpolated stories, which are crowded with echoes and repetitions and a sense of otherness. Yet what makes this novel is the way that these stories, supposedly written decades before, prefigure characters, incidents, and situations in the present. That leaves The Dollmaker with an overwhelming sense of the uncanny, even though nothing exactly strange happens.

What fascinates me about The Dollmaker, as it did with Nina Allan’s previous novel, The Rift, is that it is impossible to say whether or not we are meant to take it as a work of straightforward realistic fiction. Anything overtly weird or fantastic is restricted to the interpolated stories, which are crowded with echoes and repetitions and a sense of otherness. Yet what makes this novel is the way that these stories, supposedly written decades before, prefigure characters, incidents, and situations in the present. That leaves The Dollmaker with an overwhelming sense of the uncanny, even though nothing exactly strange happens.

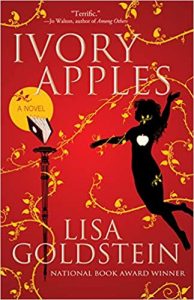

For those who like their fantasy less ambivalent, with gods and magic directly affecting the lives of humans, you might turn to Ivory Apples by Lisa Goldstein (Tachyon), though the ambivalence is still there. Well, this is a novel by Goldstein so you wouldn’t expect it to be straightforward, would you? Ivory Apples was a fantasy novel written years before under the direct influence of one of the original Greek muses. That experience was so overwhelming that the author immediately stopped writing and became a Salinger-like recluse (one of the dominant themes of the novel is that artistic inspiration is a cruel and terrifying master). But that novel acquired a devoted and obsessive fandom, and now one of the most needy and single-minded of those fans has located the family of the author and is insinuating herself into their midst with devastating consequences. Meanwhile the eldest girl, just coming to adulthood, acquires her own muse, which is likely to have as terrifying an effect on her life as happened with her great aunt. It is easy to read this novel for its vivid fantasy, but beneath that surface there is something much darker and more intricate going on.

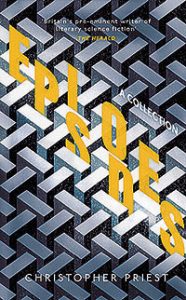

Two short story collections came my way during the year. Episodes by Christopher Priest (Gollancz) is not quite a greatest-hits collection, though it does include stories from the very beginning of his career, and essential classics such as “An Infinite Summer” and “Palely Loitering” (the collections in which they have previously been gathered are long since out of print), alongside other major works, “I, Haruspex” and “The Sorting Out”, that have not previously been collected. Furthermore, the “Before” and “After” comments on each story provide a rich insight into Priest’s work, and are themselves almost worth the cost of the book.

Two short story collections came my way during the year. Episodes by Christopher Priest (Gollancz) is not quite a greatest-hits collection, though it does include stories from the very beginning of his career, and essential classics such as “An Infinite Summer” and “Palely Loitering” (the collections in which they have previously been gathered are long since out of print), alongside other major works, “I, Haruspex” and “The Sorting Out”, that have not previously been collected. Furthermore, the “Before” and “After” comments on each story provide a rich insight into Priest’s work, and are themselves almost worth the cost of the book.

Big Cat by Gwyneth Jones (NewCon Press) is the first full-length book from Jones for far too many years, and would be welcome for that fact alone. To be honest, the title story doesn’t work for me, but the rest of the stories are well up to her usual standard, and a couple of them, “The Old Schoolhouse” and “Bricks, Sticks, Straw” for instance, probably count among her very best.

This has been a particularly good year for non-fiction. For instance, M. John Harrison: Critical Essays edited by Rhys Williams & Mark Bould (Gylphi) contains some fascinating insights into a major writer (the book includes an essay by me, but don’t let that put you off); while Sideways in Time: Essays in Alternate History Fiction edited by Glyn Morgan & C. Palmer-Patel (Liverpool University Press) is variable, but at its best contains some really interesting stuff.

But let’s face it, there is one absolutely stand-out, essential contribution to science fiction studies this year: The Cambridge History of Science Fiction edited by Gerry Canavan & Eric Carl Link (Cambridge). It’s a massive book, with 46 essays spread across more than 800 large pages of small print, and in a book of that size there are inevitable (and sometimes embarrassing) errors, and interpretations that are perhaps questionable, so it is a book to argue with. At the same time, this is the first substantial history of science fiction that treats the literature as a truly global phenomenon. From the essays here, for instance, we learn that science fiction has been a part of Chinese literature and South American literature for at least as long as it has been in North American literature. Elsewhere ,we get glimpses of science fiction in Russia and Africa, in the Middle East and India, continental Europe and Japan. Other anglophone science fictions, from Australia or Britain, for instance, maybe get less attention than they deserve, and there are places where the traditional American view of the genre still seems like the only history worth considering. Nevertheless, this book is an important first step towards presenting science fiction as something far more wide-ranging and various than we are used to considering.

But let’s face it, there is one absolutely stand-out, essential contribution to science fiction studies this year: The Cambridge History of Science Fiction edited by Gerry Canavan & Eric Carl Link (Cambridge). It’s a massive book, with 46 essays spread across more than 800 large pages of small print, and in a book of that size there are inevitable (and sometimes embarrassing) errors, and interpretations that are perhaps questionable, so it is a book to argue with. At the same time, this is the first substantial history of science fiction that treats the literature as a truly global phenomenon. From the essays here, for instance, we learn that science fiction has been a part of Chinese literature and South American literature for at least as long as it has been in North American literature. Elsewhere ,we get glimpses of science fiction in Russia and Africa, in the Middle East and India, continental Europe and Japan. Other anglophone science fictions, from Australia or Britain, for instance, maybe get less attention than they deserve, and there are places where the traditional American view of the genre still seems like the only history worth considering. Nevertheless, this book is an important first step towards presenting science fiction as something far more wide-ranging and various than we are used to considering.

Paul Kincaid has published two collections of essays and reviews, What It Is We Do When We Read Science Fiction (2008) and Call and Response (2014). His most recent book is Iain M. Banks (2017). He has been awarded the Clareson Award from the SFRA and the BSFA Non-Fiction Award.

This and more like it in the February 2020 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.