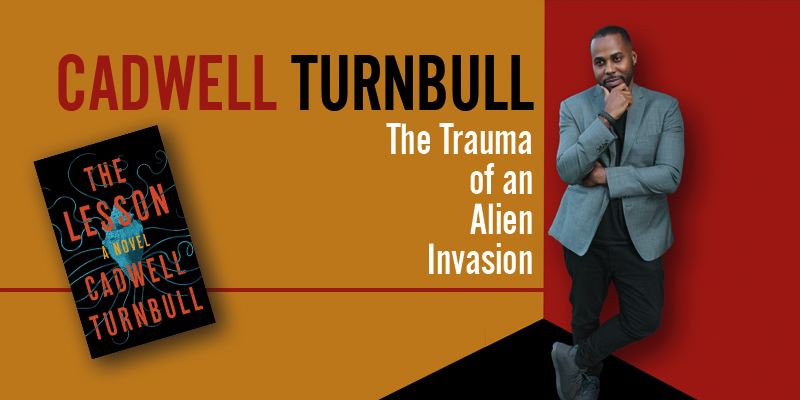

Cadwell Turnbull: The Trauma of an Alien Invasion

Cadwell Wilbur Turnbull, Jr. was born August 12, 1987 in Chevy Chase MD, and moved to his parents’ home island of St. Thomas in the US Virgin Islands when he was a month old. He grew up there, then moved to Pittsburgh PA to attend La Roche College, where he earned a degree in Professional Writing. After graduating he returned to St. Thomas for a year, where he worked as a substitute teacher. He then spent a year teaching in South Korea, and subsequently worked as a media coordinator for AmeriCorps and as a journalist on St. Thomas during the summers while attending NC State University’s MFA program, where his teachers included John Kessel; he also earned a MA in linguistics there. He attended Clarion West in 2016.

Turnbull’s first published story was “Loneliness Is in Your Blood” (2017, reprinted in The Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy 2018), followed by “Other Worlds and This One” (2017), “A Third of the Stars of Heaven” (2017), “When the Rains Come Back” (2018), “Jump” (2018), and “All the Hidden Places” (2019). Debut novel The Lesson appeared in June 2019.

He lives in Somerville MA.

Excerpts from the interview:

“The entire time I was getting my undergrad degree, I was writing fiction – I just wasn’t writing anything particularly good. I still have pieces of the novel I was trying to write at that time, and I go back and read it, and parts aren’t so bad, but when I look at it, I never think, ‘Oh, I need to clean this up.’ It’s just like, ‘This was a wash.’ I didn’t know what I wanted to write yet. It’s like that moment after you type a destination into a GPS and it’s trying to figure out the best route. I was still figuring out the best route – it just happened to take several years.

“I did my MFA at NC State. It was a really good program. It was, at the time, John Kessel, Wilton Barnhardt, and Jill McCorkle – all really great writers, and Kessel is a SF writer. I knew the stuff I tended to write was on the speculative side, though I didn’t really have those terms at the time. I was like, ‘The stuff that I write tends to be weird. This seems like a good fit for me, because it seems like there’s enough literary stuff, but also enough weird that I might be able to find a home there.’

“I was always a nerd, but not a science fiction nerd. I didn’t read a lot outside of things required for school. I read what they assigned me. There was the young YA stuff, and there was the black writers – older black writers, like Zora Neale Hurston, Alice Walker, and Mildred D. Taylor – and some of the classics. Lord of the Flies, Animal Farm, 1984, Brave New World. I tended to like the weirder stuff. I didn’t have a classification for it. It wasn’t like they said, ‘George Orwell wrote speculative fiction.’ They said, ‘1984 is a classic literary novel.’ I thought, ‘1984 is the best of these. I actually really enjoyed that one.’ I didn’t know why, but I liked what it was thinking about and what it was talking about.

“When I started thinking, ‘Maybe I’ll be a fiction writer,’ I was writing urban fiction. If I was reading for pleasure, that was the stuff I read. I remember reading Sister Souljah’s The Coldest Winter Ever. My urban fiction was bad. It was like – none of my characters had jobs, they drove to each other’s houses and had arguments about things, and there was drama. There was relationship drama, and people had cars and nice apartments, but they didn’t work. I had no concept of how adults did anything. The characters were basically high school people, but they were supposed to be 25. When I started writing in college, it was more inspired by things I watched when I was a kid. Stargate, Buffy the Vampire Slayer – I was watching a lot of speculative TV. I was also watching Star Trek movies with my mom. I liked fantasy movies. I really liked Matilda – maybe watched that a hundred times. I liked all the stuff that was kind of like our world, but with weird stuff happening, and small towns where strange things happened, and space stuff. When I started writing fiction in undergrad, I wrote the weird stuff.

“The novel I worked on as an undergrad was a retelling of the Bible, but with Lucifer as an ambiguous revolutionary figure. By the end of the book, you’re not supposed to think he’s a particularly good person, but neither is God. There’s an angel that’s in love with Lucifer, Aganel – he’s more of a spectator, but able to see that both of these figures are partly wrong. It was told mostly from that perspective, like how the first-person narrator of The Great Gatsby isn’t the central figure of the novel – he’s the eye. The book wasn’t very good, and, I learned later on, not really that original, because there are other Lucifer stories where the story’s told with sympathy for Lucifer as a character. The idea of divinity still draws my eye though, even with things that I write now.

“I find myself, at each stage, thinking, ‘Oh, now I’m taking my writing seriously,’ but what ‘taking it seriously’ means is different at every stage. I applied to the MFA because I was ‘taking it seriously,’ and I was turning in my most out-there ideas. My first stories were everything and the kitchen sink, the entire candy shop, in story form. I would get crits from my MFA peers and the professor – John Kessel was my first teacher – saying, nicely, ‘This isn’t very good. You’re doing a lot, and a lot of the stuff you’re trying to do is interesting, but it’s not a story. It’s not working. It’s a mess.’ That’s because I wasn’t taking it seriously. I thought, ‘I’m here because I want to learn how to write, so I’m going to write the craziest thing I can, and then I’ll have these people tell me what’s wrong and I’ll fix it.’

“I did that for maybe two stories, then realized that taking it seriously meant learning the craft on my own, and writing things I could manage – not shooting too high, but being practical about what I was trying to do – so I could work on the mechanics instead of just the concepts. When I started taking it seriously, I began reading a lot of stuff on my own, and even though I was doing the MFA and learning a lot in class, I was teaching myself too. I was reading things I thought were good. In the MFA workshop class, Kessel had us read short story collections, Alice Munro’s Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Loveship, Marriage and Tobias Wolff’s The Night in Question. We were reading and discussing some of those stories in class, and also doing our workshop of each other’s stories. I was studying the stories I liked painstakingly. I would go through them and look at each sentence and figure out what that sentence was doing for the entire piece. I was thinking about transitions – I was really bad at transitions. I couldn’t get people from one place to the other without walking them through everything. They had to walk down the stairs to get outside. They had to walk down the hall. It was basically me telling you every single bit of how they got to the next scene. I was like, ‘How do people do transitions?’ These were basic things I didn’t even know how to do. I was thinking about all these big ideas, but I didn’t even know how to get a character across the room, so I would read those stories over and over again.

“I was also reading some short speculative fiction – things that Kessel recommended, but some stuff of my own – and older work too: Robert Heinlein, Chip Delany, Nancy Kress. I was trying to figure out how people were doing things I thought were really good, and applying that to the stories I was writing – which went from being crazy stuff to more grounded material. Even now, I’ll have this immense world in my head, and I’ll commit one or two percent of it to the page. I’ll work little pieces in, but try to anchor the larger idea into something concrete.

“The third story I submitted for the workshop was ‘Let Them Talk’, and it became a chapter in The Lesson. That story does not look the same – it changed substantially as I wrote the novel – but that was the first time I set a story in a place that I knew, Saint Thomas. It also had the first black character I’d ever written. My earlier characters were all unraced, unspecified. They might as well have been white, because I wasn’t thinking about who they were. This was the first time I wrote a character who was a lot like me. As time went on, he became more himself, but he was the first person that looked like me and thought about things that I thought about at that time, who lived in a place where I lived and cared about things I cared about. And there were aliens, of course.

“The Lesson came out of a dream I had of aliens that had integrated into a small town, and they looked and acted in every way like us, but they responded to threats with disproportionate violence. In the dream they would kill people sometimes. I thought, ‘Okay, take this idea, write stuff that I’m familiar with, ground it in something real, and then use this to practice mechanics.’ I did a lot of thinking about craft in that story – dialogue tags, transitions, things I didn’t know how to do. I experimented with how much description I needed to describe a person. That story was me applying a lot of what I was practicing and thinking about and studying, and it was the first story where people said, ‘Wow. I knew you had it. I knew there was something in there.’ Kessel said as much – ‘No, this is really good.’ He didn’t say this in those terms, but the idea was, ‘We can actually talk about this as a serious piece and work on this. This is something that can be worked on.'”

Interview design by Stephen H. Segal. Photo by Arley Sorg.

Read the full interview in the September 2019 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.