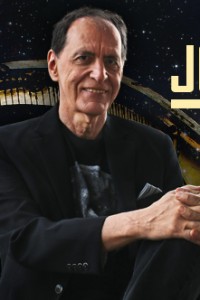

Leigh Bardugo: Radical Balance

LEIGH BARDUGO was born April 6, 1975 in Jerusalem, Israel, and grew up in Southern California. She attended Yale University, graduating with an English degree in 1997, and worked various jobs, including as a copywriter, journalist, and make-up and special effects artist.

Her debut YA novel Shadow and Bone, an epic fantasy, appeared in 2012, and began the Shadow and Bone trilogy that continued with Siege and Storm (2013) and Ruin and Rising (2014). Duology Six of Crows (2015) and Crooked Kingdom (2016), also set in the ‘Grishaverse,’ followed. King of Scars (2019) begins another related duology. Her collection The Language of Thorns (2017) includes original fairy and folk tales from the Grishaverse. The Grisha novels were optioned by Netflix, and the first season is expected to begin shooting this year. She also wrote YA comic-book tie-in Wonder Woman: Warbringer (2017), and has written some short fiction, essays, and reviews. Bardugo’s forthcoming first novel for adults, Ninth House, is a contemporary fantasy about secret societies at Yale.

She lives in Los Angeles.

Excerpts from the interview:

“I was an only child. When my mom had me, she moved in with her parents so that she could go back to school. I can’t say I grew up wild – we were in Southern California in the San Fernando Valley, so this wasn’t Little House on the Prairie. But there wasn’t a ton of parental supervision happening, and I spent a lot of time telling myself stories and keeping myself company. Writing really became important to me when I hit junior high. That was when my mom remarried. We moved to a very different kind of neighborhood, I started a new school, and things were rough for me. That was when I discovered science fiction and fantasy, and started reading it copiously and writing it almost compulsively. It was a survival mechanism for me at that point.

“When I was really little, I wrote terrible stories and poems. One was about a kid with a mean mom, who ran away and went to live with a bunch of orphans in a hotel called Pinkella Champagnella, because – sophisticated. As a child, I thought pink champagne was the height of class, and this was what fancy people did: they lived in hotels and they drank pink champagne. Actually, that still sounds really good to me. I was not a good or creative writer. I was the kind of kid writer who loved to describe the things people wore and the places they lived, and I didn’t start taking my characters on adventures until I started reading about characters going on adventures, when I really needed to believe my life would be something other than home and school and the mall. Junior high is a brutal time. Whenever I meet kids of that age, or teachers or librarians who are working with kids that age, I always say that was a really hard few years – peak awkward phase, and being in a place that I did not belong at all. My niece and nephew are so spectacularly well adjusted, and they do everything – they swim, they’re great at math, they’re just great people, and I look back to young Leigh perpetually in a rage and listening to The Cure and I don’t recognize these kids, but I’m so glad for them.

“When I went to college, I fought the English major so hard, and I think it was because I had only ever really been good at writing, and I thought, ‘Surely there’s something else I can be good at.’ I was a classics major for a short time, and a history major, and I took one class in acting, but eventually I came around to English. I loved my time at Yale, but I did not take full advantage of college. I don’t think I even understood how. I dated a guy for a while and found out he had applied for all these grants, and he would go to office hours with professors. He had been raised by professors, so it was like he knew this other language that was completely foreign to me.

“My first job out of college was for an ad firm. I absolutely had to have a job coming out of school, and I didn’t really know what I wanted to do, and I’d seen a lot of people who worked for advertising in TV and movies and it always looked like fun. Like you sit around in a room and spitball ideas and that kind of thing. I sent out 30 resumes – maybe 40 – and didn’t get a single bite. McCann Erickson, this massive firm, came to my school to recruit, and they gave us this amazing questionnaire that was so much fun. It was like, ‘Write a pitch for a cruise to the Arctic. Write an ad for the first red rubber ball,’ and I thought, ‘This is great. I can be great at this.’ The interview process was super intense, I had to borrow my friend’s suit and take the train to New York for the day. It was one of those things where you interview with 20 different people in a single day. I remember very specifically this one guy clearly didn’t like me, and he gave me one of those weird interview questions: ‘How many marbles can you fit in an Olympic-sized swimming pool?’ I said, ‘How big are the marbles?’, stalling for time. He said, ‘As big as you want them to be.’ I said, ‘I can fit one Olympic-sized marble in an Olympic-sized swimming pool.’ I was like, ‘I’ll be damned if I do math for you, buddy.’

“It gave me the sense that clearly this was an important and magical job, since it was so hard to get. They put me in account management – I wasn’t even a copywriter – and it was absolute misery. Maybe if they had put me in ad copy I would have lasted longer, but maybe it’s a blessing that they didn’t, because I was just in hell. It was just spreadsheets all day long, and I was getting paid nothing, obviously, because that’s the way that New York works. I would be there until two, three, four in the morning, generating paper. I realized all of a sudden that I not only didn’t want my boss’s job, I didn’t want her boss’s job, and I thought, ‘I’m going to quit.’ I called my parents and they said, ‘Good, you don’t belong there.’ They didn’t say, ‘Good, we’ll send you a check,’ but they said, ‘Good, you don’t belong there.’

“I quit and went to work as a temp, and worked as a secretary for a bunch of different people for months, and I lived in my little rented room in somebody else’s apartment. Eventually one of my friends got me a job interning at The Advocate, and I moved back to New Haven and slept on her couch. I think I broke up her relationship, because that apartment was not made to house three people. She ended up with someone better, anyway.

“Whatever The Advocate needed written I wrote, and I had a wonderful boss named Josh Mamis, who may still be the editor there, and who eventually just started paying me out of the goodness of his heart – he said, ‘I feel like we’re exploiting you at this point.’ I freelanced there and wherever I could get work, but this was also the beginning of the end for free weekly papers. I moved to Seattle during the dot-com boom and worked for a horrible company, then eventually quit and moved back to Los Angeles to work for a more horrible company.

“I had terrible jobs, and I did lots of weird things after that. We all got laid off when the crash came, and I worked logging tape for The Bachelor – like the lowest of the low for the TV show. They just put you in a freezing cold warehouse where you’re watching hour after hour of video and just logging it into a spreadsheet so the producers can build a story out of it. It was kind of wonderful because I was with all these out-of-work writers and directors and actors, and it was a paying job, but also an excruciating and boring job. It was like going on a hundred terrible first dates. ‘Do you have any brothers or sisters? What kind of music do you listen to?’ Now that I think about it, it was like being stabbed in the eyes.

“The best day job I ever had was writing movie trailers. But when my dad died, I kind of flipped out and felt like, ‘I cannot be in front of my computer screen anymore.’ That was in many ways very foolish, because it paid well and there was room for advancement and my boss liked me, and I was good at it.

“My dad had been sick for a long time, but his death still hit me very hard when it came, which is one of the weird things about grief. Grief really doesn’t care how prepared you are – it’s going to come for you. I have a very clear memory of sobbing in a Panda Express parking lot and thinking, ‘Wow, this is not what I thought grief looked like.’ When he passed, I just couldn’t be in my head. I was in a very solitary field, and my own thoughts were driving me insane, so I quit my job and started doing makeup and special effects. I went to makeup school, and I thought, ‘Oh, I’m going to do this and I’m going to pay my way through grad school. I’ll go get an MFA.’

“It was a terrible plan. But then two things happened, one negative and one positive. The negative thing was my depression got much worse. I didn’t understand how depressed I was, and that I was in very deep. I applied to several MFA programs, and was lucky enough to get into a couple of them, but I didn’t make a decision to go or not go. I just let it sit, because my depression was profound enough that I simply was not able to act. I was in a job that I was okay at but not great at, and that I had never viewed as a career but as a trade. The positive thing that happened was, when I worked in copywriting, I would come home and have nothing left for writing stories. That muscle was just getting fatigued all day long. Whereas when I worked as a makeup artist, I would be on set for sometimes ten or twelve hours at a time, listening to some actor talk about his cleanse or complain about his roommate, and meanwhile my brain would be generating story ideas. Even though my body was incredibly fatigued, I would come home and have all of this excitement built up to write. I don’t know if Shadow and Bone would have gotten written if I had not made that change in career. My path was definitely not a direct path.

“I assume your readers already know a lot about publishing and writing, but I feel like, so often, we fetishize the creative life. The stories we hear the most about are people who sold a book in college, or sold a book in grad school, and not the people who worked a bunch of jobs, or who were taking care of dependents, or who were paying off student loans. I want to make sure people know there were multiple times when I was working, even before I started Shadow and Bone, where I thought, ‘This is never going to happen for me. I thought I was going to be a writer, but clearly I don’t have it. I’m going to be one of those people with a tombstone that reads,

“Had potential,” and that’s going to be it.’ I didn’t publish my first book until I was 37, so if anybody out there is reading this and thinking your chance has passed, there’s no expiration date on your talent.”

Interview design by Francesca Myman. Photo by Jen Castle.

Read the full interview in the March 2019 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

I’m about to start uni, i’ll be majoring in writing, and it makes me so damn anxious not knowing about the future. About being a total fraud. My friends tell me i should study something that will give me money Surely…… so that doesn’t help either. Thank you, Leigh, you give me the chance to have some little faith on myself.