Ken Liu Guest Post–“Is It Possible to Learn About China by Reading Chinese Science Fiction?”

As a child, I was first exposed to life in the West through Chinese translations of American science fiction. While I couldn’t see E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (because back then Hollywood films weren’t shown in China), I did get to read the Chinese translation of Kotzwinkle’s novelization. To this day, I have fond memories of the nigh-incomprehensible footnote explaining Dungeons & Dragons to the reader—just try imagining accomplishing this feat in one sentence; there was no Wikipedia back then either.

I devoured such works extensively, without regard to their background or purpose: The Empire Strikes Back, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, “Helen O’Loy”…. Translations were my window upon an alternate existence, my source of knowledge of the quotidian realities of another people, of their rhythm of speech and daily life, of hopes and fears different from my own. Often, the details of daily life in America appeared to me far more fantastic than the science fictional elements. Kotzwinkle’s book was how I first learned about M&M’s (how could such a perfect food be real!), Halloween (surely this is made up…), and Speak & Spell (most certainly a magical machine that could not have possibly existed in reality). Years later, when I finally got to taste real M&M’s, I was severely disappointed, and my disappointment only spiked when I saw that the M&M’s in the script and novelization had been replaced by Reese’s Pieces in the actual film itself—a victim of the fantastically arcane magic of product placement.

Using American science fiction to understand America turned out to be both a source of wonder as well as a path fraught with danger. Without understanding the filmic and literary tradition that E.T. was in conversation with, I couldn’t appreciate the subtlety of the story’s commentary on the emotional bleakness of life in American suburbia, realized through a stylized representation at once timeless and specific, nor could I read it as a retelling of the story of Peter Pan using the tropes of SF. I couldn’t tell what was metaphorically being said about the reality of life in America through the fantastic figure of E.T., nor could I decipher what was in fact dreamlike and symbolic in the depiction of the daily routines of a lonely boy. No footnotes would have been adequate to such an interpretive task, which required a lived experience and the unvoiced, shared understandings of a people, not just comprehension of the words on the page.

I still believe in the importance of translations. There is no substitute for hearing the voices of writers from other countries, to experiencing the worlds of their imagination. The threats facing all humanity require that we listen to voices from every corner of the globe, to not pretend that our own particular perspectives can substitute for the whole picture of the human experience.

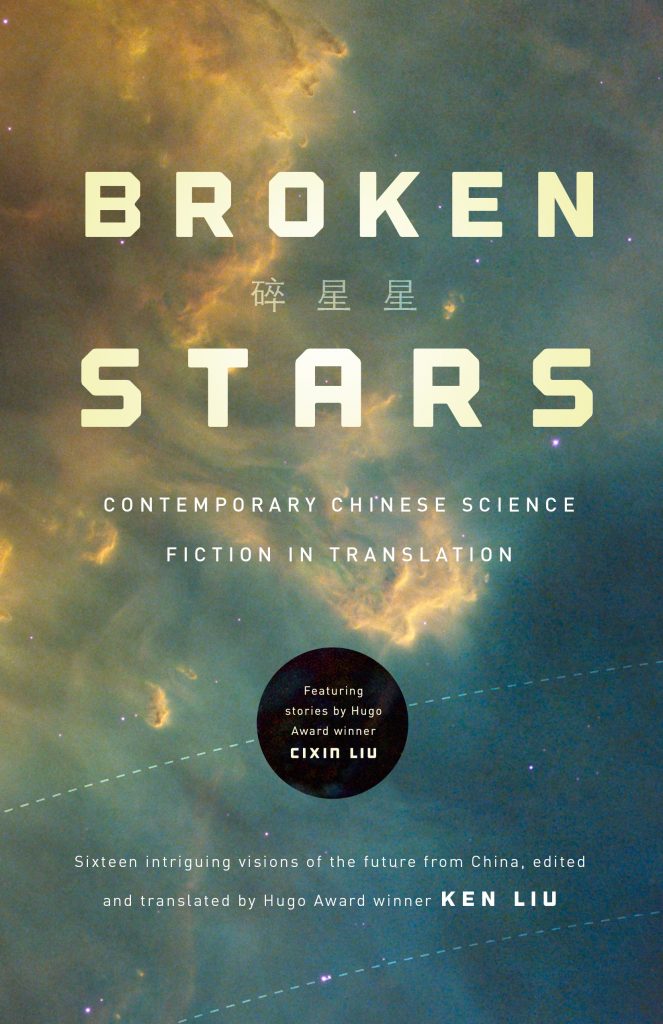

This is why I’ve edited Invisible Planets and now Broken Stars, both anthologies featuring some of the most exciting SF voices from China. Contemporary Chinese science fiction has a vitality and boldness evinced in its own internal contradictions and diverse expressions, and there is a power to personally encountering another literary world, embedded in a tradition different from our own, that cannot be replaced by volumes of scholarship or criticism.

Given my childhood experience, I’m sympathetic to Western readers who approach translations of contemporary Chinese science fiction with the aim of learning about China. At the same time, however, I’m deeply skeptical of the utility of this approach and must caution readers against common interpretive pitfalls.

Fiction isn’t reportage, and fiction assumes certain interpretive frameworks and background knowledge in the reader to make sense of the character motivations, plots, and especially deviations from reality. A story comes to life as a collaborative effort between the writer and the reader, and when the reader isn’t steeped in the same assumptions made by the writer, metaphor shear is almost inevitable. Reading Chinese science fiction will surely teach the reader something about China, but it is very hard to appreciate just how limited that knowledge is.

Just as I, as a child, couldn’t make sense of much of the layers of meaning beneath the surface in E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, most Western readers, not conversant with the political, social, and literary conversations in which Chinese science fictions stories are participating, risk missing the point of these stories for Chinese readers. A translator may re-create the linguistic performance of a story for a new audience, but they cannot re-create the cultural milieu in which that performance takes place.

This isn’t to say that there is no point in reading translations, but to caution against the temptation to overgeneralize, to draw conclusions about reality based on fiction, to think that we already know all there is know, merely because we understood every word we read. Indeed, the risk of misunderstanding is perhaps greater today than ever: with Wikipedia, with more media outlets than ever in human history, with more pictures, videos, and nonfiction accounts about life in China than were ever available to me as a child about life in America, it’s easy for a Western reader to assume that they have the necessary context to draw definitive conclusions, to pronounce judgments, to think that they understand.

But some kinds of understanding requires lived experience, not mere secondhand knowledge. It is fine to apply our own interpretive frameworks to these stories, so long as we acknowledge to ourselves that we’re doing so. We can still experience the sense of wonder and draw conclusions about the human condition from these tales without mistaking our interpretations as the interpretations of readers for whom these stories were originally intended.

I loved E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial as a child, though I knew, even at the time, that what I got out of the story was surely not the same as what an American reader would have gotten out of it. The book cast a new light upon my own existence, revealed to me how little I knew of the world, and made me ask questions that I wouldn’t have asked otherwise. That was a gift.

A humility toward the limitedness of our own interpretive reach, both individually and collectively, is freeing rather than limiting.

Ken Liu’s fiction has appeared in F&SF, Asimov’s, Analog, Strange Horizons, Lightspeed, and Clarkesworld, among other places. He is the author of The Grace of Kings, and has won a Nebula, two Hugos, a World Fantasy Award, and a Science Fiction & Fantasy Translation Award, and been nominated for the Sturgeon and the Locus Awards. He edited and translated the Hugo Award winning Three-Body Problem by Cixin Liu, as well the 2016 Chinese science fiction anthology Invisible Planets. He lives near Boston with his family. You can find him online at www.kenliu.name, on Twitter as @kyliu99, and on Facebook as @authorkenliu.