Competing Against Trump by Ian Mond

Nothing in 2018 can possibly compare to the breadth of imagination, range of tone, and unconventional spelling present in Donald Trump’s tweets. His early morning tantrums proved to be the most riveting, most extraordinary, most majestic fiction I read this year. It says something about authors around the world that when faced with Trump’s prodigious talent they never dropped their heads; they continued to write and publish the most astonishing works.

Considering the insane reality of Trump, Brexit, and Australia’s revolving door of Prime Ministers, you’d think I’d gravitate toward escapist fiction. Not the case. My favourite novels for 2018 were all about the politics. Some of these works were in direct conversation with the current President and his Administration. For example, Leni Zumas’s Red Clocks considers an America where the Government has passed a law that provides embryos with personhood and bans abortion and in-vitro fertilization. With Mike Pence as Vice President and the Federalists owning the Supreme Court, it’s a future that, sadly, isn’t difficult to imagine. In Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation her protagonist – in a bid to avoid people – plans to sleep away the year with a cocktail of potent, experimental drugs. The novel is set at the turn of the 21st Century, the climax coinciding with 9/11, arguably the pivotal event that led America to where it is now. Moshfegh’s message is simple: it’s time we all woke up. Grady Hendrix also leverages off the Trump phenomena in his terrific third novel, We Sold Our Souls, an updated, revisionist take on the heavy metal horror novels of the ’80s and ’90s. Hendrix’s America is one where hopelessness has become a disease, where conspiracy theories are rife, and where the promises made by Trump to America’s rust belt were never realised.

Trump, and the changing face of America, wasn’t the only political issue that novelists dealt with. Ling Ma’s Severance uses the end of humanity – the majority wiped out by a plague – to dissect late-stage capitalism and provide an honest and moving portrayal of the immigrant experience. Danny Denton’s wonderful debut, The Earlie King & the Kid in Yellow, considers the question of class in a dystopian setting, a drowned Ireland where constant rain has eroded the infrastructure and frazzled technology. Then there’s the brilliant Theory of Bastards by Audrey Schulman, possibly my favourite book for the year (it’s a toss-up between it and Severance). Schulman deals with climate change, society’s reliance on technology, and the medical profession’s narrow views on chronic pain, especially when it comes to women. It’s also, very much, a book about sex and attraction, brought into focus by the stars of the novel, a clan of bonobos.

Over the past few years, gender has become a hot political issue, one taken up by the alt-right to ridicule those on the left. Fortunately, there are authors who recognise that the question of how we identify is more than just about who can use which restroom. Shortlisted for this year’s Man Booker, Daisy Johnson’s extraordinary debut, Everything Under, is a gender-fluid retelling of Oedipus told in lush, but never cloying prose. L. Timmel Duchamp’s introspective Chercher La Femme, as the title suggests, puts gender front and centre as an all-female crew head off to a distant world to make first contact with an alien species. It’s a novel that speaks directly to the science fiction of the ’50s and ’60s, which rarely, if ever, found significant roles for women. The book, though, that blew me away was Akwaeke Emezi’s debut, Freshwater. She tells the story of Ada, who, at a young age, is possessed by Nigerian spirits (the ogbanje). It’s a raw, confronting, but ultimately hopeful novel about gender identity, self-hood, and the literal and metaphoric pain of transition. All three novels are worthy of a Tiptree nod.

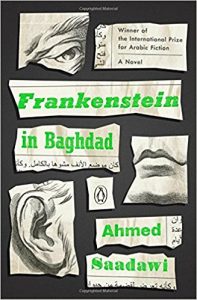

Not to be outdone, the novels in translation I read this year also had a strong political bent. Frankenstein in Baghdad by Ahmed Saadawi, deservedly shortlisted for the Man Booker International Prize, places the eponymous monster amongst the suicide bombings and devastation of Baghdad in 2005. It’s a book that pokes fun at those in power, but never shies away from the brutality and senseless death of the Iraq War, the monster stitched together from the scattered remains of the innocent. Less violent, sporting a cover and title promising all sorts of naughtiness, is Yoss’s Condomnauts. It’s a 50,000-word space opera, crazy with ideas, that also takes an unvarnished, passionate look at poverty and the marginalised. In Yoko Tawada’s The Emissary (AKA The Last Children of Tokyo) a series of ecological disasters and mutations has meant that while the adults of Japan are living longer, the children are dying before they reach maturity. This unsettling premise, with dollops of satire – such as the Japanese Government eliminating foreign words like “overalls” and “jogging” – is, at its heart, a story of love and affection between a great-grandfather and his ailing great-grandson. Less political, but unlike anything I’ve read this year, is the perplexing but rewarding Sisyphean by Dempow Torishima. Consisting of four linked novellas, Torishima creates these grotesque, fleshy, remarkable worlds where humanity, altered beyond all recognition, survives, adapts, and more often than not dies gruesomely.

Not to be outdone, the novels in translation I read this year also had a strong political bent. Frankenstein in Baghdad by Ahmed Saadawi, deservedly shortlisted for the Man Booker International Prize, places the eponymous monster amongst the suicide bombings and devastation of Baghdad in 2005. It’s a book that pokes fun at those in power, but never shies away from the brutality and senseless death of the Iraq War, the monster stitched together from the scattered remains of the innocent. Less violent, sporting a cover and title promising all sorts of naughtiness, is Yoss’s Condomnauts. It’s a 50,000-word space opera, crazy with ideas, that also takes an unvarnished, passionate look at poverty and the marginalised. In Yoko Tawada’s The Emissary (AKA The Last Children of Tokyo) a series of ecological disasters and mutations has meant that while the adults of Japan are living longer, the children are dying before they reach maturity. This unsettling premise, with dollops of satire – such as the Japanese Government eliminating foreign words like “overalls” and “jogging” – is, at its heart, a story of love and affection between a great-grandfather and his ailing great-grandson. Less political, but unlike anything I’ve read this year, is the perplexing but rewarding Sisyphean by Dempow Torishima. Consisting of four linked novellas, Torishima creates these grotesque, fleshy, remarkable worlds where humanity, altered beyond all recognition, survives, adapts, and more often than not dies gruesomely.

Two novels that resonated strongly with me consider an alternate history where the Holocaust never happened. In Simon Ings’s The Smoke, The Bund (Yiddish speaking Marxists) take over the world with the discovery of a “biophotonic ray.” The off-the-wall narrative – featuring a marvellous piss-take of Gerry Anderson’s UFO – critiques the inequality and class divide inherent in a post-human utopia. But what really affected me was the implicit suggestion that The Bund, with their ubermensch views regarding humanity, fill the historical vacuum left by the Nazis. With Unholy Land, Lavie Tidhar imagines a possible history where a Jewish homeland is established in North Africa during the early part of the 20th century rather than the Middle East after WWII. The novel is playful and meta-fictional with a dab of Roger Zelazny, but it presents a reality where the Jewish people avoid the Holocaust at the expense of hundreds of thousands of dispossessed Ugandans.

What else did I love in 2018? Stephen Moffat’s adaptation of the 50th anniversary Doctor Who story, Day of the Doctor, which he scripted, is a perfect nugget of joy (it’s also, to my surprise, Moffat’s first novel). Keeping with the theme of time-travel, Kate Mascarenhas’s The Psychology of Time Travel is that rarest of things, an intelligent and fresh take on a well-worn concept. Catherynne M. Valente’s Space Opera is the most fun I had with a novel, channelling Douglas Adams and featuring an intergalactic song contest inspired by Eurovision (because, of course!), with the fate of humanity resting in the hands of one-hit-wonders The Absolute Zeros.

Of the horror novels I read this year, the ones that stood out – aside from the aforementioned We Sold Our Souls – were Tide of Stone by Kaaron Warren and I Am the River by T.E. Grau. Both authors effectively employ unconventional narrative techniques to get under the reader’s skin. When it comes to experimental fiction, the most remarkable – with a genre sheen – was Murmur by Will Eaves, shortlisted for the Goldsmiths Prize. The novel details Alan Turing’s conviction for gross indecency, but replaces Turing, and those he was close to, such as Joan Clarke, with fictional facsimiles – Turing’s analogue is named Alec Pryor. It’s a strange but stunning book about dreams, about identity, and about memory.

I don’t generally read sequels or books in a series, but this year saw Dave Hutchinson wrap up his four-book Fractured Europe series (talk about political) with the complicated, convoluted, but oh-so-smart-and-satisfying Europe at Dawn. By the Pricking of Her Thumb, Adam Robert’s sequel to The Real Town Murders is a smart mystery with a dark, intense edge that left me emotionally exhausted.

Of the young adult novels I read, I Still Dream by James Smythe is his best work to date; Bash Bash Revolution by Douglas Lain is similar to Ready Player One but so much smarter (and funnier); James Bradley’s The Buried Ark – book two in the Change series – is a wonderful follow up to The Silent Invasion and last… but not least… Christopher Barzak’s Gone Away Place is a compelling ghost story and a sensitive meditation on grief and trauma.

Finally, it’s been an honour and a privilege to write reviews for Locus this year. I can’t say it’s been a childhood dream, because I didn’t read the magazine when I was a kid, but since I picked up my first issue I’ve dreamt of having a review column of my own. I’d like to thank Jonathan Strahan for giving me the opportunity, for making me a small part of the Locus family.

This and more like it in the February 2019 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.