2018: A Year on Edge by Paul Kincaid

It’s been a hard year. The rule of ignorance and selfishness in Trump’s America; the wilful destruction of economic probity at the behest of perceived (and probably illusory) political necessity in Brexit Britain; the continued rise of the far right in Hungary, Poland, Italy, France, and elsewhere. All of this is, at some point, going to feed through into a wave of fictions built around the ongoing sense of fear and mistrust, the feeling that the world is out of kilter. We are not quite there yet, but we might be getting a foretaste of it in some of the year’s more interesting novels.

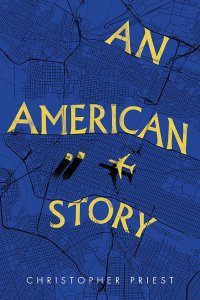

I’ve spent the year immersed in the work of Christopher Priest for the book I’m currently in the middle of trying to write, so I immediately saw An American Story (Gollancz) in terms of his eternal themes and interests: the malleability of memory and of reality, and the way each can shape the other. There is no solid and reliable world in Priest’s fiction; we are liable at any moment to find everything we trust whisked away from under us, but when the novel is built around conspiracy theories about 9/11 it all feels doubly uncertain. And given that the novel is set in post-Brexit Britain and sees the rise of an authoritarian government in America, the chill wind of our current unreality seems to whistle through the book.

One of the ways in which British science fiction has traditionally reacted to troubling times has been through the catastrophe story, so it is telling (not to say disturbing) that the catastrophe is back. Shelter by Dave Hutchinson (Solaris) paints a society slowly getting itself back together again after a century of hard-scrabble, hand-to-mouth existence. But what is going to destroy this painful struggle to survive is human nature. Distrust and ignorance bring a new wave of violence and destruction just at the point when things might have been starting to get better. Meanwhile, the Brexit referendum was barely a gleam in David Cameron’s deluded eye when Hutchinson began work on his Fractured Europe sequence, which he now brings to a triumphant close with Europe at Dawn (Solaris); but I can’t think of anything that better captures the madness of this season. Hutchinson is a fine writer, inventive and engaging, and in these two novels he seems to have caught the drumbeat of the moment better than anyone else.

One of the ways in which British science fiction has traditionally reacted to troubling times has been through the catastrophe story, so it is telling (not to say disturbing) that the catastrophe is back. Shelter by Dave Hutchinson (Solaris) paints a society slowly getting itself back together again after a century of hard-scrabble, hand-to-mouth existence. But what is going to destroy this painful struggle to survive is human nature. Distrust and ignorance bring a new wave of violence and destruction just at the point when things might have been starting to get better. Meanwhile, the Brexit referendum was barely a gleam in David Cameron’s deluded eye when Hutchinson began work on his Fractured Europe sequence, which he now brings to a triumphant close with Europe at Dawn (Solaris); but I can’t think of anything that better captures the madness of this season. Hutchinson is a fine writer, inventive and engaging, and in these two novels he seems to have caught the drumbeat of the moment better than anyone else.

Another telling engagement with the contemporary is Arkady by Patrick Langley (Fitzcarraldo) which tells of two young brothers struggling with the simple task of existence in a world where corporations rule. It is a wonderfully written dystopian novel – there is no doubt about that – but I am still not entirely sure whether this is a vision of the very near future, or a documentary glimpse of the underside of our contemporary society from a perspective most of us will fortunately never share. Either way, the crumbling squats, the rotting narrow boat that gives the novel its title, the landscape of muck and despair, provide for a haunting and affecting novel.

As I said, I have no way of knowing (or caring) whether Arkady is, strictly speaking, science fiction or not. But then, as is so often the case, the books that most caught my attention this year are those that defy genre norms, that don’t fit into easy categories. Chief among these, and to my mind easily the best novel of the year, was The Black Prince by Adam Roberts (Unbound), built upon an unproduced radio drama written by Anthony Burgess. In one sense, this is an account of the life and career of Edward, The Black Prince, from teenage war hero to premature death. But though the novel sticks pretty close to the facts of the case and what we know of the times, this is far from being a conventional picture of the Middle Ages. For a start, Roberts has lifted his prismatic structure directly from John Dos Passos’s high-modernist classic, USA, which means that we have, anachronistically, stream-of-consciousness passages headed “Camera Eye” and surveys of contemporary events headed “Newsreel”, techniques that work extraordinarily well in bringing the period to life. And there is a wide range of viewpoints, some directly involved in the major events of the period and others not, including one section from the viewpoint of a dog, another from a character immediately after his execution, and a third from someone who seems to be inadvertently performing a holy parable. It is, in other words, a novel that shifts restlessly between the realistic and the fantastic.

Another fascinating take on the historical is Tell Them of Battles, Kings and Elephants by the French writer Mathias Enard (Fitzcarraldo, translated by Charlotte Mandell). In 1506, Michelangelo, during one of the regular periods when he was out of favour with the Pope, was invited by the sultan of Constantinople to design a bridge to span the Golden Horn. Now we know that Michelangelo would later incorporate ideas from the dome of the Hagia Sophia in his later architectural work on the Vatican, but the historical record doesn’t suggest that he ever left Italy. Enard, however, has Michelangelo travelling to Constantinople, where he becomes enmeshed in Ottoman intrigues and, more significantly, finds himself both enchanted and disturbed by a way of life at odds with everything he has known in Rome. If this is not exactly alternate history, neither is it straight historical fiction.

One of the essential building blocks of the fantastic in Europe has to be Dante’s Divine Comedy. Now there is a new version of the first part, Inferno, simply called Hell, not so much translated as, in his own words, “decorated and Englished” by Alasdair Gray (Canongate). As is typical of everything Gray has written, his verse is robust, colloquial, often crude and always vivid, which give this rather strange poem an entirely new freshness.

I’ve not read much short fiction this year (other than Priest’s forthcoming collection, Episodes, about which more next year, I’m sure), but The Doll’s Alphabet by Camilla Grudova (Fitzcarraldo) contains some odd and oddly disturbing tales. As is the way with surrealism, however, the stories are better the shorter they are, as if the longer tales are weakened by the need to devise a plot, so it is the intermittent stories of only a handful of pages that really set this collection on fire.

Finally, the one work of non-fiction that everyone is talking about this year is Astounding by Alec Nevala-Lee (Dey Street). This purports to be a joint biography of John W. Campbell, L. Ron Hubbard, Isaac Asimov, and Robert A. Heinlein, though in truth Asimov and Heinlein are little more than sup porting players to the madness that is the collision of Campbell and Hubbard. The book really is as good as everyone says, but it isn’t the hymn to the golden age of science fiction that it is sometimes presented as; rather it is a testimony to how much of the science fiction of the 1940s was shaped by prejudice, by duplicity, and by incredibly narrow social and literary horizons. Honestly, when you read what was going on behind the scenes, it is amazing that anything remotely readable emerged at that time.

Paul Kincaid has published two collections of essays and reviews, What It Is We Do When We Read Science Fiction (2008) and Call and Response (2014). His most recent book is Iain M. Banks (2017). He has been awarded the Clareson Award from the SFRA and the BSFA Non-Fiction Award.

This and more like it in the February 2019 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.