Cory Doctorow: The Engagement-Maximization Presidency

Incentives matter.

The dominance of ad-supported businesses online created an odd and perverse incentive to “maximize engagement” – to go to enormous lengths to create tools that people used for as long as possible, even when this made the product worse. Think of how Google added a “trending searches” dropdown to the default search-bar on Android, so that any time you went looking for a specific piece of information (the number of centimeters in an inch, treatments for sunburn, the phone number of your kid’s school), you got three or four intriguing search-strings suggested to you that were related to some passing moment. It is vanishingly unlikely that these will have any bearing on the majority of your searches, but that doesn’t mean you won’t click on them: even if you’re trying to find out who won the 1988 World Series, it’s hard to resist the temptation to click on an option like “trump threatens nuclear armageddon.”

These features weren’t dreamed up from whole cloth. The modern model of software development calls for the creation of a “minimum viable product,” with the smallest quantum of useful functionality, which is deployed and used by real people, whose usage patterns are analyzed for tiny improvements that might increase the “key performance indicators” (KPIs) that the company is looking for. In the case of ad-supported businesses, the number one KPI is to increase the number of ads you see before you go somewhere else, because each ad seen is a potential revenue-generator for the company.

Possible new refinements are tried out in controlled experiments called A/B splits, experiments that are highly automated, such that software developers are more like the designers of an evolutionary experiment that will direct their products, rather than designing the products themselves – you can think of this as similar to the way that some Christians square evolution through natural selection with scripture: “God made the universe and its natural laws; those laws acted upon life in order to produce us. God is still our Creator, and evolution is His tool.”

Tying commercial success and programmers’ pay, bonuses, and career progression to “engagement” has created an entire arsenal for capturing and directing attention without regard to the effect of these techniques on the user’s subjective experience of the product. A company that needs you to be engaged with its product is not necessarily concerned with whether you enjoy that engagement: if you visit Google to look up a cookie recipe, get directed to a news-cycle about impending nuclear armageddon and spend the afternoon terrifying yourself and never bake the cookies, that is a success for Google, even if you go to bed hungry and anxious at the end of it.

Tying human attention to financial success means that the better you are at capturing attention – even negative attention – the more you can do in the world. It means that you will have more surplus capital to reinvest in attention-capturing techniques. It’s a positive feedback loop with no dampening mechanism, and, as every engineer knows, that’s a recipe for disaster. Machines that have a system for speeding up and no system for slowing down eventually tear themselves apart and explode.

Science fiction has many allegories for this process, but my favorite comes from Peter Watts’s 2002 novel Maelstrom, the second book in his Rifters series. Watts is an evolutionary biologist whose science blends wonderfully with his science fiction, creating tales that are riveting and important, using storytelling to critique our technologies.

Maelstrom is concerned with a pandemic that is started by its protagonist, Lenie Clark, who returns from a deep ocean rift bearing an ancient, devastating pathogen that burns its way through the human race, felling people by the millions.

As Clark walks across the world on a mission of her own, her presence in a message or news story becomes a signal of the utmost urgency. The filters are firewalls that give priority to some packets and suppress others as potentially malicious are programmed to give highest priority to any news that might pertain to Lenie Clark, as the authorities try to stop her from bringing death wherever she goes.

Here’s where Watt’s evolutionary biology shines: he posits a piece of self-modifying malicious software – something that really exists in the world today – that automatically generates variations on its tactics to find computers to run on and reproduce itself. The more computers it colonizes, the more strategies it can try and the more computational power it can devote to analyzing these experiments and directing its randomwalk through the space of all possible messages to find the strategies that penetrate more firewalls and give it more computational power to devote to its task.

Through the kind of blind evolution that produces predator-fooling false eyes on the tails of tropical fish, the virus begins to pretend that it is Lenie Clark, sending messages of increasing convincingness as it learns to impersonate patient zero. The better it gets at this, the more welcoming it finds the firewalls and the more computers it infects.

At the same time, the actual pathogen that Lenie Clark brought up from the deeps is finding more and more hospitable hosts to reproduce in: thanks to the computer virus, which is directing public health authorities to take countermeasures in all the wrong places. The more effective the computer virus is at neutralizing public health authorities, the more the biological virus spreads. The more the biological virus spreads, the more anxious the public health authorities become for news of its progress, and the more computers there are trying to suck in any intelligence that seems to emanate from Lenie Clark, supercharging the computer virus.

Together, this computer virus and biological virus co-evolve, symbiotes who cooperate without ever intending to, like the predator that kills the prey that feeds the scavenging pathogen that weakens other prey to make it easier for predators to catch them.

All through the 2016 election campaign, this story kept coming to my mind. Donald Trump is manifestly not very smart in the sense of understanding nuance or being able to discern the truth among many propositions. But he is very good at acting like a machine-learning system that is co-evolving with the attention-maximization systems built into our ad-driven systems.

Listening to Trump campaign is like listening to a “psychic” perform a cold reading: “Someone here is thinking of a relative; no, it’s a friend; a close friend; a male friend; no, a female friend; an older woman; no, a young woman; a young woman who’s dead; no, she’s in trouble; she’s sick; no, she’s disabled; she’s rich; no, she’s poor; her name is Mary; no, Sara; no, Tanya – who here is thinking about their friend, a disabled young girl named Tanya?”

Trump campaigns like this, a gabble of contradictory statements that is steered by approbation from his crowd: the more they cheer him on, the more of whatever he was just saying he gives them – and Trump is very good at detecting people who are cheering him on (this also works well on Twitter, of course).

Since Trump’s audiences are extreme, and since they like things that outrage others, Trump’s statements make for excellent clickbait: it’s nearly impossible to hear one of the pronouncements that emerges from this evolutionary process whose selective pressure is cheers from bigots without repeating it, “Did the President just say _______?”

That’s also helpful to Trump. Bigotry is relatively thin on the ground, making it hard to economically reach bigots who are vulnerable to hearing Trump’s message and being influenced by it. When the large body of people who aren’t bigots repeat Trump’s messages – even incredulously – they increase its reach at no cost to Trump, increasing the likelihood that one of the broken people who believe in fairy tales about sharia law and Mexican rapists will encounter the idea and be swayed by it.

Since the electorate is largely deadlocked – only a minority of people vote, and gerrymandering and other forms of political engineering has produced a near 50-50 split among voter support for the two major parties – anything that mobilizes some of the potential voters out there in the “dark matter” of the electorate can tip an election one way or another.

Trump and ad-tech co-evolved without ever colluding: he is the engagement-maximization president.

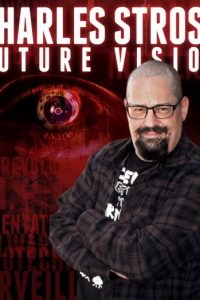

Cory Doctorow is the author of Walkaway, Little Brother, and Information Doesn’t Want to Be Free (among many others); he is the co-owner of Boing Boing, a special consultant to the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a visiting professor of Computer Science at the Open University and an MIT Media Lab Research Affiliate.

This column and more like it in the May 2018 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.