When It Was 2017, It Was a Very Good Year, by Graham Sleight

I’ve been writing these year-end summations for over a decade now, and I find it hard to think of a year when there’s been more really good science fiction and fantasy to record. (Of course, I’ve also read a few duds – omitted below – but then that’s always the case.) I’m not sure why 2017 has seen so many strong books. There aren’t many unifying themes across the works I’ve read, and it’s probably too early to see many stories that reflect the current strange political moment. In genre terms, some of the books I’m going to mention are pushing at the formal boundaries and some aren’t; their tones vary widely, as do their approaches to their material. Perhaps it’s just a lucky moment to be able to read science fiction and fantasy.

I’ve been writing these year-end summations for over a decade now, and I find it hard to think of a year when there’s been more really good science fiction and fantasy to record. (Of course, I’ve also read a few duds – omitted below – but then that’s always the case.) I’m not sure why 2017 has seen so many strong books. There aren’t many unifying themes across the works I’ve read, and it’s probably too early to see many stories that reflect the current strange political moment. In genre terms, some of the books I’m going to mention are pushing at the formal boundaries and some aren’t; their tones vary widely, as do their approaches to their material. Perhaps it’s just a lucky moment to be able to read science fiction and fantasy.

Like its predecessor The Race, Nina Allan’s The Rift tackles family dynamics as well as the wider world: grippingly, its protagonists have to answer the question How do we arrive at believing the things we think are true? In the space of only a couple of books, Allan has become one of the most important UK SF writers. Charlie Jane Anders’s Six Months, Five Days, Three Others added to its well-known and award-winning title story several extra works that confirmed the author’s exceptional narrative facility and knowledge of the genres in which she works. Paul Cornell’s Chalk was as personal a book as this author has yet written, applying the tools of fantasy to the cruelties that children are capable of.

I’m a long-standing admirer of John Crowley’s work, but even remembering classic earlier books such as Engine Summer and Little, Big, Ka: Dar Oakley in the Ruin of Ymr was a comparably major work. More to the point, it seemed like a summation of many of Crowley’s longstanding preoccupations: how we tell ourselves stories, how we can find ourselves in the middle of stories, how time and the world can shape or change stories. If it didn’t sound like damning with faint praise, I’d say that above all it’s a wise book. Crowley’s Totalitopia was a slim collection of fiction and non-fiction whose preoccupations with better worlds seemed especially topical. Aliette de Bodard’s The House of Binding Thorns continued where its predecessor The House of Shattered Wings left off. Its fantastical Paris is as vivid as ever, and even if this book is partly about picking up the pieces from the last, it also points the series in several intriguing new directions.

By the unarguable logic of alphabetical order, the next few books are all by authors who, one way or another, are not entirely within the mainstream SF/F tradition. As Gary Wolfe and others have been arguing for a long while, genres are melting into one another, and so this kind of crossover work should not be a surprise; nonetheless, each of these books seemed particularly autonomous and individual. Steve Erickson’s Shadowbahn continued the author’s anatomisation of the American past as a world of amnesia and gaps – in this case taking as its starting point the 2021 reappearance of the World Trade Center towers in the Dakota wilderness. Shadowbahn offers no easy ways out of the labyrinths of memory, but it is perhaps more accessible than some of Erickson’s other works. Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West applied the tools of the fantastic to the refugee crisis of the last few years, fusing a dream-like logic with an engaged urban realism. Elizabeth Hand’s Fire. was, like the Crowley collection mentioned above, a worthwhile brief volume of thematically related fiction and non-fiction. M. John Harrison’s You Should Come with Me Now was a long overdue collection of some of the shorter work this most singular of authors has been publishing over the last few years. By now, it’s unhelpful to think of Harrison’s work just in terms of his ambivalence about genre conventions: the stories collected here reflect ambivalence on just about every front. The usefulness of language, causality rather than contingency, the weight of the past: all of these are up for debate here. Nick Harkaway’s lengthy, multi-voiced Gnomon was, well, the most Nick Harkaway book he’s yet published. Funny, serious, focussed, all over the place, it will take more than one reading to unpack.

Kameron Hurley’s The Stars Are Legion put some of the concerns from the author’s earlier Nyx books on a grand space-operatic scale without losing any of her engagement with the day-to-day physicality of life. John Kessel’s The Moon and the Other was, among other things, a book that questioned assumptions about gender, taking off from the shorter works the author has published about a colonised Moon. N.K. Jemisin’s The Stone Sky concluded the sequence begun with The Fifth Season, edging towards science fiction in the explanation of how its world works. Jemisin’s scarred, fragile world is surely one of the defining settings for early 21st-century SF. Ann Leckie’s Provenance was set in the same universe as the earlier Ancillary books, but picked up a different story: perhaps not as striking as its predecessors, it was nevertheless solidly enjoyable. Yoon Ha Lee’s Raven Strategem was also a follow-up, in this case to the acclaimed Ninefox Gambit. There was greater narrative skill on display here than in the earlier book, but also some loose ends: this is the middle volume of a trilogy and its full importance will doubtless become clear in time.

The Library of America’s two-volume set of Ursula K. Le Guin’s Hainish Novels and Stories is self-recommending: it includes two of the most central 20th-century SF novels, The Left Hand of Darkness and The Dispossessed, together with earlier works, short stories (including those that made up the superlative Four Ways to Forgiveness) and other hard-to-find material.

The Library of America’s two-volume set of Ursula K. Le Guin’s Hainish Novels and Stories is self-recommending: it includes two of the most central 20th-century SF novels, The Left Hand of Darkness and The Dispossessed, together with earlier works, short stories (including those that made up the superlative Four Ways to Forgiveness) and other hard-to-find material.

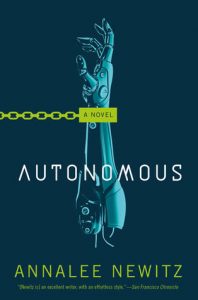

Paul J. McAuley’s Austral took seriously one possible response to climate change: Antarctica as a refuge for humanity. As ever, McAuley was thorough about working out the human consequences of this premise. Ian McDonald’s Luna: Wolf Moon was an engaging continuation to the author’s competing-dynasties-on-the-Moon series. Sam J. Miller’s The Art of Starving was marketed as YA, no doubt because it’s a coming-of-age tale – in this case, about growing up gay and suffering from eating disorders. But Miller’s imagination is much tougher and more interesting than a synopsis might imply: this is an extremely accomplished first novel. Annalee Newitz’s Autonomous was also a first novel, and a fun, slick read: robots vs. pirates, drugs and genetics, freedom and capitalism. Philip Pullman’s La Belle Sauvage had to do double duty: as a prequel to the events in the original His Dark Materials sequence, and as a curtain-raiser for future volumes of the projected Book of Dust trilogy. It succeeded admirably at the first, telling a contained story with care and enough refinements to the original premises to maintain interest. If its position in the larger scheme of things seems unclear at the moment – if it’s not clear why Pullman had to tell this story – then perhaps we just need to wait for some answers.

Kit Reed’s Mormama was doubtless not planned as the last work to come from her late and astonishing burst of novel-writing, but sadly it seems we have to take it as such. Here Reed is playing with a number of known conventions – the Southern Gothic, the haunted house, multiple viewpoints on a single event – with knowing skill. Kim Stanley Robinson’s New York 2140 successfully achieved what his earlier Science in the Capital Trilogy had been aiming for: making apparent and storyable the consequences of the slow-moving apocalypse of climate change. One had a sense that all the necessary arguments about science, society, and economics were aired within the scope of this book, to form a devastating picture of what will happen if this goes on. Christopher Rowe’s Telling the Map was, like Reed’s, a very Southern book: a collection of some of the best stories from this author’s career to date. As often in Rowe’s work, strangeness was close to hand. Sofia Samatar’s Tender also collected works with a strong sense of place, though in this case they ranged more widely. My own preference is for Samatar’s novels, but there’s no doubt that this is an important body of work.

George Saunders’s long-awaited first novel, Lincoln in the Bardo was an exceptionally moving story about the death of a child: specifically, Abraham Lincoln’s son Willie at the height of the US Civil War. The book embodies, through its many voices, a moment when things seem held in suspense: the fate of the country, the soul of the child. Like its predecessor Mr. Penumbra’s 24-hour Bookstore, Robin Sloan’s Sourdough was perhaps too slickly told, too immured in its Bay Area world to really catch hold, but there’s no denying the enjoyment to be had in reading it. Calling Rivers Solomon’s An Unkindness of Ghosts a generation starship story would be to miss the point entirely; it’s a story about the ways in which power preserves itself, at human cost. It happens to use a SF frame to make its points with exceptional clarity. Peter Straub’s The Process revisited the world of Tillman Hayward from A Dark Matter, chillingly. And finally, Jeff VanderMeer’s Borne presented flying bears, biotech, capitalism, and survival in the ruins to superbly deranging effect. Leaving aside the sheer quality of many of these books, one has only to consider how various they are to see that it was, indeed, a very good year.

Fifteen books of the year:

Nina Allan, The Rift (Titan)

John Crowley, Ka: Dar Oakley in the Ruins of Ymr (Saga)

Aliette De Bodard, The House of Binding Thorns (Gollancz/Ace)

Mohsin Hamid, Exit West (Riverhead)

John Harrison, You Should Come with Me Now (Comma)

Nick Harkaway, Gnomon (Heinemann)

John Kessel, The Moon and the Other (Saga)

N.K. Jemisin, The Stone Sky (Orbit)

Sam J. Miller, The Art of Starving (HarperTeen)

Annalee Newitz, Autonomous (Tor)

Philip Pullman, La Belle Sauvage (Knopf)

Kit Reed, Mormama (Tor)

Kim Stanley Robinson, New York 2140 (Orbit)

George Saunders, Lincoln in the Bardo (Bloomsbury)

Jeff VanderMeer, Borne (Macmillan)

…and, inevitably, Ursula K. le Guin’s Hainish Novels and Stories (Library of America).

This article and more like it in the February 2018 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

Why did you omit the duds? Isn’t it the reviewer’s obligation to steer the reader away from the bad as well as toward the good? If you don’t name them, how can we know what they are? Fundamentally, reviews are (or certainly should be) a buyers’ guide. Anything less than openly discussing both sides of the good-bad spectrum is, therefore, not acceptable. (Already “providing enough good ones to read” is much beside the point.)