Cat Sparks: Strange Directions

Catriona Sparks was born September 11, 1965 in Sydney Australia. She studied film making and photography at the City Art Institute, and worked as a media monitor, political photographer and graphic designer for many years, as well as traveling through Europe, the Middle East, Indonesia, the South Pacific, China, and the Americas.

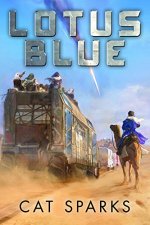

Sparks began publishing short fiction in 2001, and has since published around 70 stories, including Ditmar Award winners ‘‘A Lady of Adestan’’ (2007), ‘‘All the Love in the World’’ (2010), ‘‘Scarp’’ (2013), and ‘‘The Seventh Relic’’ (2014), Aurealis Award winner ‘‘Hollywood Roadkill’’ (2007), and Ditmar and Aurealis winner ‘‘Seventeen’’ (2009). Some of her short fiction was collected in The Bride Price (2013). Debut novel Lotus Blue appeared in 2017.

With partner Rob Hood she ran Agog! Press from 2002-2008. She was fiction editor at Cosmos Magazine from 2010-2016. She is also an artist, and won Ditmar Awards for her art in 2000, 2003, 2004, and 2009. In all she has been nominated for 12 Aurealis Awards and 29 Ditmars for her writing, editing, and artwork.

Sparks attended the first Clarion South Writers’ Workshop in 2004, and was one of 12 students chosen to take part in Margaret Atwood’s The Time Machine Doorway workshop during the 2012 Key West Literary Seminar. She was a Writers of the Future prize winner in 2004. She is pursuing a PhD in media, culture, and creative arts at Curtin University.

Excerpts from the interview:

‘‘My parents were science fiction fans. What I like to say is, they put my bassinet down in front of Doctor Who, and that was it. They weren’t rabid fans, but it certainly wasn’t a lesser grade of literature to them. I was never prohibited from reading adult material. Anything they had, my sister and I were allowed to read if we wanted. Books were an important part of my upbringing. There was never a time when science fiction wasn’t a massive part of my life. You know how your parents keep little bits of school work? Whenever I was listing my favourite things when I was a kid, I’d put, ‘I like animals and science fiction.’ It was always there.”

*

‘‘I sold my first story in 2000, after spending nine years trying to write something publishable. By trying, I mean really trying. I did workshops. I took courses. I was in three writing groups, at it hammer and tongs. Because I also had the visual arts going, I wasn’t really aware nine years had passed. I only counted the years up later. Had I realized how crap I was at writing, I think I would’ve thrown in the towel. But I loved the community so much. When my boyfriend worked at Galaxy, I took photographs for the shop. This would never happen now, but they actually paid me to photograph authors, as did the local Dymocks store. I photographed Douglas Adams on three separate occasions. The first time, nobody knew who he was – it was that early. I remember looking at the authors signing and thinking, ‘I would like that to be me.’ The irony is I absolutely hate signing books now. Signing makes me feel like such a fraud. I have to go on tour when I get home, but I’d rather do my taxes and then have a root canal.”

*

‘‘The Australian spec fic scene is small. Everybody eventually knows everybody. I met my partner Rob Hood at some book event –- probably one of Terry Dowling’s launches. I used to love writing groups, particularly the social aspect. It would be at someone’s house, we’d all go around, in the early days we would read stories to each other out loud (this was pre-e-mail – that’s how old I am). We’d all bring snacks and sit around a big table. In this one group, we had the crown, a plastic tiara with jewels on it, and when anyone sold a story, we would have a crowning ceremony. As we got better we have several coronations in the same meeting. That was great for camaraderie.”

*

‘‘Margaret Atwood’s Time Machine Doorway workshop was fantastic. You had to apply with the first chapter of a post-apocalypse novel. I happened to have one of those, so I submitted it, and got in. But I had no money, so didn’t know how I was going to get to Florida. I scored an Australia Council Emerging Writer’s grant, enough money to live for a year and was allowed to use some of that money for the Key West Seminar. A wonderful experience. KWLS normally don’t do science fiction – Atwood was the driver behind that year’s theme, I believe. I was terrified of meeting her because a lot of people have Atwood stories. There were 12 of us, and we all sat down, and there was dead silence. She’s like Yoda, right? She came in with these little white cards that said ‘stop talking’ and put them on the table. She said, ‘If you need to use these just pass them around.’ She’s got a great sense of humour. I try not to be a loud and overwhelming person but when I get excited I just can’t shut up. It was okay. She and I got on very well, probably partly because I’d turned up with an actual sci-fi novel. The other participants had turned up with sci-fi, too, but if it had been a bird poetry workshop, they would have written bird poetry, or whatever. They weren’t science-fiction people. One or two of them had interest in it, but they were there for her. She’s the real deal. She still gets so much flak from our community about that unfortunate ‘talking squids in outer space’ comment. I do not share her view as to the difference between science fiction and speculative fiction, but I can’t stand the fact that someone of her caliber has to go through so much rubbish because of one stupid comment.”

*

“Lotus Blue went through many shapes and shifts before deciding on what sort of novel it really wanted to be. I’d initially been trying to write a YA, presuming that because the story I wanted to tell needed a young protagonist, YA was the right genre fit. Only it didn’t work out that way. The language wasn’t right. My story was about a young person cast adrift in a landscape that’s been trashed by adults, their laws and their machinery across a vast timeframe. It’s the story of a girl who finds out she isn’t as human as she thought, and the ramifications of this are terrifying.

“I didn’t set out to write a climate change story, but it is easy to see how I ended up with one. My still-not-finished PhD examines the intersection point of ecocatastrophe science fiction and climate fiction. No way to stop that bleeding over into anything else I’m working on. I can barely keep it out of my conversation.

‘‘All of this has resulted in a novel that for some readers is a little too unwieldy. A couple of negative reviews reckon there are too many characters. That there is too much going on. Personally, I’m bored to tears of the chosen one who saves the world. Saving our real world is going to be a group effort. For me, the theme I was trying to resonate with is, we’ll all do our little bit, and that’s how you bring the monster down. I gave my protagonist, Star, as much agency as a real person might be expected to have. She starts out with more bravado, then finds out how tough everything is, pushes on, and decides she’s willing to die to save the future if it comes to that. A choice we could all possibly make ourselves.”

*

‘‘For my PhD, I’m writing about the dying days of capitalism, because I think that’s the big issue behind climate change today. It’s all about capitalism and how it absolutely has to change to accommodate the future. I have nothing but undying respect for Kim Stanley Robinson who has been talking about this stuff for years. If I were starting my PhD today I would do it entirely on Stan Robinson’s body of work. Someone needs to do this – look at all his work in sequential order, because he’s telling one big story. He’s the man. He was 20 years ahead of everybody else.”

*

‘‘Here’s my take on writing. I’m 51 years old. I’m going to write the things I want to write. That is more important to me than any other consideration. After losing both my parents, I think like a mortal being. I’m already doing the thing I most want to do with my life. I just want to keep doing more of it.’’