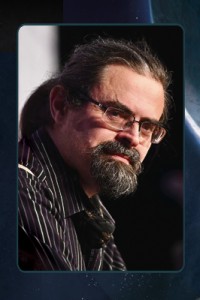

Alastair Reynolds: Expanding Universe

Alastair Preston Reynolds was born March 13, 1966 in Barry, South Wales, and spent his childhood in Cornwall and Wales. He earned degrees in astronomy from the University of Newcastle in England (1988) and a PhD from the University of St. Andrew’s in Scotland (1991). In 1991 he moved to The Netherlands to work for the European Space Agency, where he remained (apart from a break in 1994-96 to do a postdoc at Utrecht University) until becoming a full-time writer in 2004.

Reynolds began writing SF stories and novels in his teens, selling debut ‘‘Nunivak Snowflakes’’ to Interzone (1990). Notable short fiction includes ‘‘A Spy in Europa’’ (1997), ‘‘Galactic North’’ (1999), ‘‘Great Wall of Mars’’ (2000), ‘‘Diamond Dogs’’ (2001), ‘‘Zima Blue’’ (2005), Seiun Award-winner ‘‘Weather’’ (2006), Sidewise Award-winner ‘‘The Fixation’’ (2009), Hugo Award finalists ‘‘Troika’’ (2010) and Slow Bullets (2015). Some of his short work has been collected in Zima Blue and Other Stories (2006), Galactic North (2006), Deep Navigation (2010), and Beyond the Aquila Rift: The Best of Alastair Reynolds (2016).

His first books were set in the Revelation Space universe: Revelation Space (2000), BSFA winner Chasm City (2001), Redemption Ark (2002), novella Turquoise days (2002), Absolution Gap (2003), and The Prefect (2007). Standalone novels include Century Rain (2004), Pushing Ice (2005), House of Suns (2008), Terminal World (2010), and Revenger (2016). He co-wrote The Medusa Chronicles (2016) with Stephen Baxter, an authorized sequel to Arthur C. Clarke’s ‘‘A Meeting with Medusa’’ (1971). His Doctor Who novel Harvest of Time appeared in 2013. The Poseidon’s Children trilogy began with Blue Remembered Earth (2011) and continued with On the Steel Breeze (2013) and Poseidon’s Wake (2015). In 2009, he signed a £1 million deal with Gollancz for ten books.

Reynolds returned to Wales in 2008, and lives there with wife Josette Sanchez, whom he met in The Netherlands in 1991.

Excerpts from the interview:

‘‘I signed a ten-book deal in 2009. It’s not been as smooth a process as it could have been. By rights I should be near the end of those ten books now, on book eight or so. I should be well into it, and I’m still only on book five at the moment. There have been a few speedbumps on the way, and a few delays. But it’s okay. It does give me that security of not immediately worrying about the next contract. I felt going into it that I had more or less written ten books in ten years before I started that contract, so it was more of the same, really. But life throws stuff at you that you didn’t see coming.”

…

‘‘Stephen Baxter and I are old friends. When I first started moving in science fiction circles, because I didn’t come up through fandom, I began to meet some of my peer group – people who were publishing in the magazines at the same time. I met Steve way back, probably about 25 years ago. We’ve been friends ever since. We don’t see each other that often – he lives at the other end of the country from me – but we do keep in touch. We like each other’s work. We were just e-mailing, talking about collaborations. I floated this idea that if ever Steve and I were to collaborate, we should do the authorised sequel to Clarke’s ‘A Meeting with Medusa’. I was half-serious. It had been at the back of my mind for a long time, that I would like to go back to that story. Steve liked the idea. At that point, we had no idea of the practicalities, legal permissions, or whether the publishers would like the idea or not. It’s not like a sequel to 2001. Unless you’re a Clarke aficionado, you probably haven’t read that story. But if you like Clarke, you probably will have read and liked it. We both felt it was worth pursuing the conversation. We had editors and agents involved, and then the Clarke estate. There was some understandable caution initially, but they did eventually agree to the idea. I don’t think there was any editorial approval. We told them what we were going to write, and we stuck to that. They didn’t want us to use the original novella. We wanted to put it in the book as a kind of giveaway for people who hadn’t read the original, but they weren’t keen on that. I think they felt it would detract from sales of The Best of Arthur C. Clarke. We had to accept that. It meant that right until the last minute, when we were writing the opening chapters of the book, we weren’t sure if we were addressing an audience who’d read the original story or not, because we weren’t sure it was going to be in the book. We had one version that sort of assumed you’d read it, and one that didn’t. We had to put the second version in. It kind of gives you a bit of an overview of what the story was about.”

…

‘‘That whole Beyond the Aquila Rift project was blessedly painless. I didn’t have time to sit and curate my own best-of collection. I don’t think writers should. You should hand that selection to a third party who can look at it with a more detached judgmental eye. Jonathan Strahan and Bill Schafer at Subterranean had a conversation about what was going to be in the book. I was involved in that conversation – I was allowed to chip in – but ultimately, their decision was going to be final. There were stories I liked that didn’t make the cut, stories Jonathan liked that didn’t make the cut, stories Bill liked that didn’t make the cut. There were stories that we all liked, but that didn’t make it for reasons of length, or there were some contractual hurdles to work around. You don’t want an entire book full of space opera, do you? You want a bit of variety in there as well. My most significant contribution was writing the introduction and the story notes for the collection. It was fun. I’ve done story notes for some of the other collections – you risk going over the same ground and repeating what you’ve done the last time. What I had in my favour was that I keep extensive records. For virtually every story, I have about ten iterations before I got to the final version, as well as all the notes I made for myself. I keep all that stuff. I can go back to a story that’s 15 years old, and I know the day I came up with that idea, so I could cut and paste those notes into my story comments. I used to think, ‘If it’s a good idea I won’t forget it.’ When I have the experience of going back to those notes, I think, ‘Bloody hell, that’s a good idea – I’d forgotten about it.’ So I do tend to make more extensive notes now.”

‘‘The ideas for the novel Revenger go back ten years, and I also have the notes to prove it. I started thinking about the setting ten years ago. I went back to it five years ago. It’s an itch that’s got to be scratched. The idea is you have these little worlds you have to break into, and you have a limited time in which to break into them, so you have a kind of heist scenario. You have an unknown amount of time to break into these planetoids, get treasure, and get out. It’s a high-risk occupation. I started to write some stories using that premise ten years ago, and I was trying to fit them into other universes, and it just wasn’t working. The other seed of Revenger came from when I really fell in love with science fiction, around the time I was 16. That’s when I was absolutely besotted with Larry Niven and the Known Space stories. I really loved them, particularly the playfulness of the world: maverick characters, colourful technologies, exotic aliens, mysteries and adventure to be had in a crowded, colourful universe. I was 15 when I read Ringworld, and it was the first book I read that was more than 200 pages long, which says something, doesn’t it? The way books have gone these days. I wanted to come up with a collection of short stories that felt like an updating of the Known Space universe. What I wanted was that sense of humans that co-exist and trade with aliens, and use their technology, so the ships are built around a bit of alien tech here, a bit of alien tech there. I started creating notes for a set of stories that were going to be in a very far future, in a sort of Dyson set of worlds around the sun, populated by human characters, but with aliens figuring in the story as well. I had the notes, but I never could find the time to make anything of them. Then a year or two ago, I was casting around for an idea for the next novel, and I thought, ‘Hang on, I’ve got that set of notes, and I’ve got that earlier stuff about little worlds – maybe there’s enough there to get going.’ Another genesis of it goes back to the Doctor Who novel, because that was significantly shorter than any book I’d written at that point: it was 110,000 or 115,000 words, by necessity. The BBC didn’t want a long Doctor Who novel, and it was longer than they wanted anyway. All my other books have been 150,000 or 180,000, sometimes over 200,000 words. I really enjoyed writing the Doctor Who novel, and in particular I enjoyed editing it, because it was manageable. I’ve got a better chance of getting close to something I could be pleased with if it’s a shorter novel. My agent liked that as well. For a few years he’d been saying I could benefit from doing something at the shorter length. My editor was keen on it as well. I myself wanted to do something punchy, fast-paced, going back to what I read when I was 16. Nova was like 200 pages long, and it’s got a whole universe, a whole future history, crammed into this miracle of a book. That’s the gold standard. I haven’t got there, but that’s what I’m aiming for. Revenger is 140,000 words, but it’s still my shortest novel to date, other than the Doctor Who novel. I’d like to keep them short from now on, but knowing me the next one will be back to 180,000 words.”

Read the complete interview in the January 2017 issue of Locus Magazine. Interview design by Francesca Myman, Alastair Reynolds photo by Barbara Bella.