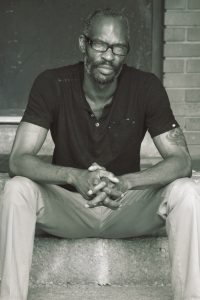

Tim Pratt: Closing Doors

Timothy Aaron Pratt was born December 12, 1976 in Goldsboro NC. He traveled with his mother as a child, living in Missouri, Texas, Louisiana, and West Virginia before settling back in Goldsboro. Pratt went to Appalachian State University in Boone NC, graduating with a BA in English in 1999, and attended the Clarion Writers Workshop that summer. He worked as an advertising copywriter briefly before moving to Santa Cruz CA in 2000, where he spent a year as a tech writer and office manager for a disability advocacy company. In 2001 he relocated to Oakland and began working as an editorial assistant at Locus, where he is now a senior editor and occasional reviewer.

Pratt began publishing genre material professionally with poem ‘‘Bacchanal’’ in Asimov’s (2001). ‘‘Soul Searching’’ won a Rhysling Award for best long poem in 2005. Some of his poetry was collected in If There Were Wolves (2006).

Pratt’s first professional story sale was ‘‘The Witch’s Bicycle’’ (2001). Other notable stories include Nebula Award finalist ‘‘Little Gods’’ (2002); Hugo Award winner ‘‘Impossible Dreams’’ (2006); Stoker Award finalist ‘‘The Dude Who Collected Lovecraft’’ (2008, with Nick Mamatas); and Theodore Sturgeon Memorial Award finalist ‘‘Her Voice in a Bottle’’ (2009). ‘‘Hart and Boot’’ (2004) was reprinted in The Best American Short Stories: 2005. Some of his short fiction has been collected in Little Gods (2003), World Fantasy Award finalist Hart & Boot & Other Stories (2007), and Antiquities and Tangibles (2013). He publishes a new short story every month for subscribers to his Patreon at www.patreon.com/timpratt.

First novel The Strange Adventures of Rangergirl (2005) was a Mythopoeic Award finalist, and won the Emperor Norton Award for best Bay Area novel. His Marla Mason urban fantasy series began with Blood Engines (2007, as T.A. Pratt), and continued with Poison Sleep (2008), Dead Reign (2008), and Spell Games (2009). Pratt self-published additional series novels Bone Shop (2009), Broken Mirrors (2010), Grim Tides (2012), Bride of Death (2013), Lady of Misrule (2015), and Queen of Nothing (2015). Final volume Closing Doors is forthcoming.

Other books include science fantasy The Nex (2010), gonzo-historical The Constantine Affliction (2012, as T. Aaron Payton), standalone contemporary fantasies Briarpatch (2011) and Heirs of Grace (2014), and short novel The Deep Woods (2015). He has also written gaming tie-ins for Forgotten Realms, Pathfinder Tales, and others properties.

Pratt edited Star*Line, the magazine of the Science Fiction Poetry Association, from 2002 to 2004. With his wife Heather Shaw, he co-edited ’zine Flytrap from 2003 to 2008, with a one-off revival issue in 2014. He edited reprint anthology Sympathy for the Devil (2010) and co-edited original anthology Rags and Bones with Melissa Marr (2013).

Pratt was a finalist for the Campbell Award for best new writer in 2004. He lives in Berkeley CA with his wife and their son, River.

Excerpts from the interview:

‘‘There are so many authors doing what I do that we have a name now: hybrid authors. Hybrids combine different things, and hybrids are stronger and more robust. There are tons of people now who do traditional publishing and also self-publish, or crowdfund some projects through Kickstarter, or publish short stories through Patreon, or whatever. It’s no longer either/or. I’ve been doing the hybrid thing for years, but now it’s so widespread it’s almost weird when people don’t. I’ll talk to authors who have thriving careers with big publishers, and they’ll say, ‘I have this weird little passion project, or this niche thing I want to do.’ Or, ‘I had this outline I wrote that we sent around years ago and nobody wanted to buy it, but I still care about it.’ Now there are options for projects like that. Crowdfunding especially has changed the threshold for what makes a project viable, and it works best for writers that are somewhat established, because you need a crowd. If you already have a career in traditional publishing, it’s easier to reach an audience with weird things that might not make enough money for your big publisher to take them on. Maybe you want to do a book that’s too niche or different for your main publisher. Now you can.”

…

‘‘I’m a short-story guy. Stories are what I’m good at, and occasionally great at. I’ve gotten to the point where I’m a pretty good novelist, but stories are where I excel, and I’ve written a few things I’ll go to my grave happy with. I’ve never written a novel I’m completely pleased with. After I started publishing novels regularly, I almost completely stopped writing short stories. I’d write them when I was solicited for an anthology, but writing for anthologies almost always means writing for a theme, or to a particular length, or with a particular tone. I rarely did the thing I used to love doing: getting an idea and just writing it, without worrying about how long it was going to be, or if it was going to be funny or scary or sad, or SF or fantasy or horror. I made my name (inasmuch as I have a name) from writing stories that way, but after novels took over my time, I stopped. ‘Write more stories’ was always on my mental to-do list, but it was way at the bottom, after the paying work, so I never prioritized it.”

…

‘‘It’s getting tricky for the midlisters. We’re going extinct. And the small press isn’t the same, either. It used to be that what a small press could offer was making a book. Well, now anyone can make a book. You can hire someone for not that much money to do your layout, buy some stock art or find an illustrator you like online and ask to use one of their pieces, and hire a cover designer who can turn that art into something attractive. You can hire developmental editors, copyeditors, proofreaders. You’re looking at an outlay of maybe hundreds of dollars, and that’s assuming you don’t have the skills to do any of it yourself, and you can get a nice-looking book, sell it, and keep all the money for yourself. The small presses used to have access to distribution channels that self-publishers don’t, but now anyone can publish with all the major online retailers. There are still good small presses with a lot to offer, ones with good relationships with bookstores, and dedicated bases of readers, and presences at conventions, and publicity skills, and good editing: those things all have great value. Subterranean Press is great, and I did a book with PS Publishing last year. Tachyon does fantastic books. Presses like that also offer a certain critical imprimatur: if they publish you, you’re probably worth reading. But there are other independent presses that don’t have that much prestige, or as many connections, and that don’t offer anything an author can’t simply do for themselves. We have more choices now.”

…

‘‘Most of my best friends who are writers write children’s books, if not exclusively, then at least in part. They’ve given me lots of advice. One of the things that made sense to me was that when you write young adult books, it’s very much about the inner life of the characters. Sometimes very little happens, externally, and it’s largely about processing emotions, figuring things out, dealing with your thoughts, and finding your place in the world. Middle grade is more about stuff happening. Younger kids don’t question things as much. You can have a magical thing happen to an eight- or ten-year-old, and they’ll roll with it. It allows you to avoid what I’ve always called the ‘blot of mustard problem.’ (You know, in A Christmas Carol, where Scrooge sees a ghost and tells himself it’s a hallucination brought on by indigestion from undigested beef or a blot of mustard.) I write a lot about magic intruding into the modern world, and when you do that, you have to deal with the protagonist’s natural disbelief. They have to say, ‘Is this a dream? Have I gone mad? Have I been drugged?’ Sometimes it’s important to have them wrestle with their belief… but more often you just want to get them to a point where they’ll plausibly accept the magic, so you can get on with the story. There are tricks to make that seem psychologically plausible, but in a middle grade, you don’t have to worry so much. You can just say: ‘Look, magic.’ And the child characters will accept it and act accordingly.”

…

‘‘I just like to try different things. I wrote a space opera proposal, which my agent is sending around now. If anybody bites on that, it will be my next project. There are a couple of other things I want to explore. There’s a character in my Marla Mason novels, a trickster figure, who’s very morally ambiguous. I have an idea for a novel about her, about revenge. I’ve wanted to do a big crazy revenge novel for a while. I love Joe Abercrombie’s Best Served Cold, and I like the Parker novels by Richard Stark, which are usually about someone being wronged and taking revenge. Right now I’m writing another Pathfinder Tales book, the fourth in a series about a con artist named Rodrick and his best friend, a magical sentient sword of living ice. I always liked Elric and Stormbringer, and I always liked Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser. One day I thought, ‘What if, instead of all the tortured angst, Elric and Stormbringer had the same sort of relationship that Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser have?’ A boy and his sword, partners against the world, two halves of a sundered whole. My talking sword is curmudgeonly and mostly wants to sleep on piles of gold all day, because he has the soul of a dragon, and his wielder wants piles of gold too, for all the obvious reasons. The first one was called Liar’s Blade – they didn’t like my preferred title Bastard, Sword, but I used it for a story about the characters later – and the third one, Liar’s Bargain, is out later this year. I like quest novels, but I like quest novels where everybody in the party has a secret ulterior motive and is planning to betray everybody else. Right now I’m writing the fourth book, Liar’s Destiny, which is about the dangers of relying on a prophecy. I love writing this series because it’s mostly banter and sword fighting, 80,000 words of jokes and derring-do and selfish people being forced to do heroic things, because the alternative is too horrible to contemplate.”

Read the complete interview in the April 2016 issue of Locus Magazine. Interview design by Francesca Myman.