Jack Skillingstead: Ups & Downs

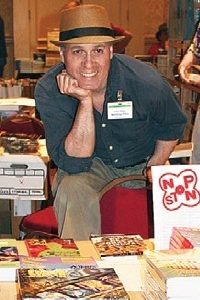

John Anthony Skillingstead was born October 24, 1955 in a working-class suburb of Seattle WA. He attended community college from 1974-76 before dropping out to work in a cannery in Alaska. He also lived a year in Maine, where he eventually returned to marry Kathy Scanlon in 1985; they later divorced, but have two adult children. In 2011, he married fellow SF writer Nancy Kress. They live in Seattle, where Skillingstead works for Boeing.

John Anthony Skillingstead was born October 24, 1955 in a working-class suburb of Seattle WA. He attended community college from 1974-76 before dropping out to work in a cannery in Alaska. He also lived a year in Maine, where he eventually returned to marry Kathy Scanlon in 1985; they later divorced, but have two adult children. In 2011, he married fellow SF writer Nancy Kress. They live in Seattle, where Skillingstead works for Boeing.

In 2000 Skillingstead entered a writing competition sponsored by Stephen King and was one of five winners. In 2003 he began publishing stories in small-press magazines, but his first professional sale was Sturgeon Award finalist ‘‘Dead Worlds’’ to Asimov’s (2003). He has since published numerous stories, most in Asimov’s, but also in F&SF, Realms of Fantasy, assorted anthologies, On Spec, and Talebones. Some of his short work was collected in Are You There and Other Stories (2009).

Skillingstead’s first novel Harbinger appeared in 2009, and new novel Life on the Preservation was published earlier this year, expanding his eponymous story from 2006.

Excerpts from the interview:

‘‘I believed I needed to do something big and commercial with this novel. Never mind that I’d never written anything like that (and even reading consciously commercial fiction sort of turns my lights out), I was going to do one that was good. Anyway, I spent about two years attempting that, over and over again, and the results were not pretty. I threw all my silly plot-heavy ideas out and started over, letting the thing evolve naturally. This was better, but the story became so complex that first readers were getting confused. So I spent yet another year reworking the material.

‘‘Life intersects writing all the time – unless you’re trying to write a stupid adventure novel! A lot of stuff was going on, including the relationship with Nancy Kress that led to our getting married. And my son from my first marriage had become this outlaw graffiti artist, and I became interested in that world. So magically, my character in Life on the Preservation became a graffiti guy, too. It really set the tone for me, and it allowed me to bring in all this stuff I hadn’t thought about before, including all the anxiety and paranoia that go along with being an outlaw. I always try to write a story or book that doesn’t depend on what Nancy refers to as Tortured Lonely Guy. But Tortured Lonely Guy has been good to me!

‘‘Every writer who’s worth anthing has got an itch he can’t stop scratching, and the more personal that itch, the better – the more authentic it makes the stories. Most of my short stories that work well feature Tortured Lonely Guy in one form or another. My earlier versions of Life on the Preservation did not. But in the final published draft I’m back in territory I’m familiar with, and the whole story is opened up, based on that one decision. The novel was also influenced by various movies, like Groundhog Day and Dark City. I like those repetitive time-loop things and the idea that something’s going on behind the curtain.”

‘‘Every writer who’s worth anthing has got an itch he can’t stop scratching, and the more personal that itch, the better – the more authentic it makes the stories. Most of my short stories that work well feature Tortured Lonely Guy in one form or another. My earlier versions of Life on the Preservation did not. But in the final published draft I’m back in territory I’m familiar with, and the whole story is opened up, based on that one decision. The novel was also influenced by various movies, like Groundhog Day and Dark City. I like those repetitive time-loop things and the idea that something’s going on behind the curtain.”

…

‘‘Like all writers, I have obsessions with certain types of material. I have my itch to scratch. I’m always obsessed with meaning. I veer back and forth. Sometimes I think, ‘Of course, everything in life has meaning.’ If nothing has meaning, things are pretty bleak. My point of interest with it is, ‘Does it matter what’s true, or does it only matter what you believe?’

‘‘Looking from the other perspective, my theory is that, just as evolution gave us physical traits to deal with the world outside us, there’s also a sort of psychological evolution that allows us to know that we’re going to die but at the same time not really believe it, so that way we can function in the world. If you really believed it, you’d never get out bed (and plenty of depressed people don’t). Carl Jung, when he was actually treating patients, talked about this. He said his healthiest patients were the ones who acted as though their personal existence would continue uninterrupted even beyond death.”

…

‘‘Friends of mine who are writers are always second-guessing their careers. These are people who have been publishing about the same amount of time as I have. What I hear from people who have been publishing longer (like Nancy, or Connie Willis) is that it’s just ups and downs, ups and way downs, and then your career seems to be over, and then it’s going up again. It’s nothing you can really plan. Whatever you have, you always want more, and you don’t want to slip down. The only way to not think about such things is to work on something new.”

…

‘‘I wrote a new book last year. This one did not take four years! I was a little more disciplined about it. There have been quite a few rewrites, and we’re just starting to shop it.

‘‘Some of the novel is set in 1947, then it’s contemporary, and then it goes back to 1947, and then it’s in Atlantis. The title so far is Vegas Apocalypse. The character’s a 16-year-old Tortured Lonely Girl. Her parents are killed in the beginning. It has some of the classic contemporary YA situations, but in Vegas. There’s a character, Vina, who has a tattoo of fairytale briar vines, and it eventually develops that there’s some magic involved with this, and she collects souls. Like the inverse of a vampire, she has to get you to accept her invitation, to be willing to surrender your guard to her. My characters find themselves inside this tattoo, looking out, and there are wicked, long thorns and vines everywhere, like the thicket surrounding Beauty’s castle. My character looks up, and she can see the lightbulb in the room they were in, but it seems distant. The deeper she goes in, that lightbulb eventually becomes the moon, with clouds scudding before it, with a terrible, cold drizzle, and she finds all of these other people that have been caught in various soul prisons. Vina’s contemporary incarnation is of this girl with the tattoo, but it goes back thousands of years, so as my character manages to make her way deeper and deeper toward the original source, she winds up in Regency England, and Rome, and all these places, except they’re all prisons, with other people trapped there for centuries, who’ve lost all motivation. You know, like depressed writers!’’