Paul Di Filippo Reviews Stephen Baxter’s The Massacre of Mankind

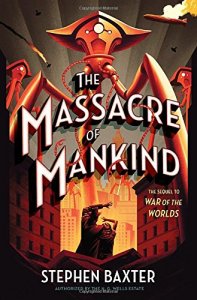

The Massacre of Mankind, by Stephen Baxter (Crown 978-1-5247-6012-0, $27, 496pp, hardcover August 2017 (UK: Orion/Gollancz 978-1473205093, £18.99, 464pp, hardcover) January 2017

In 1995, Stephen Baxter crafted an authorized sequel to H. G. Wells’s The Time Machine, titled The Time Ships. I recall enjoying it immensely, and thinking that Baxter was a fine choice for such a project, and should do more such, in between his original work. Little did I know that it would be two decades and more before I got my wish.

In 1995, Stephen Baxter crafted an authorized sequel to H. G. Wells’s The Time Machine, titled The Time Ships. I recall enjoying it immensely, and thinking that Baxter was a fine choice for such a project, and should do more such, in between his original work. Little did I know that it would be two decades and more before I got my wish.

Of course, one motivating factor for the new book–just as it was for the commemorative appearance of The Time Ships on the hundredth anniversary of its predecessor–is that 2017 is an anniversary year for the serialization of H. G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds, which appeared in Pearson’s in 1897. (Its book publication occurred the following year, so that Baxter can really extend the anniversary across two years.)

In any case, Baxter’s offering now joins a select assortment of Wellsian spinoffs, from Alan Moore’s The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen on down, proving once again just how fertile and seminal and influential old Herbert George was and remains.

Baxter has gone to great lengths to establish believable continuity between his text and Wells’s, across many parameters, all this groundwork serving as foundation for extending the tale. So rather than dive headfirst into a recitation of the plot–not all of which can be revealed, for fear of creating spoilers–perhaps the initial thing to do is examine how he has cleverly built his bridges.

Baxter has chosen as his primary protagonist Julie Elphinstone, who played a pretty relevant part in the original. She was the wife of the brother of the original narrator, whose escape from the Martians constituted some vital passages. That last-cited figure, the narrator, forever unnamed by Wells, is now revealed as one Walter Jenkins, suffering from shellshock to the current day, and obsessed with the quiescent quandary presented by the Martians. His brother, Frank, is currently divorced from Julie, and a medico. These three souls serve as a vital link to the preceding War, having experienced it firsthand and bringing their perspectives to the new encounter. To this cast Baxter adds imagined folks, among them Harry Kane, a brash American journalist, whose later career is conflated with that of Orson Welles (hence, I believe, justifying the clue of the Kane surname); and Bert Cook, a typical Brit prole of the sort beloved by Wells, who eventually comes off as a kind of Ballardian “in love with entropy” outlaw. Add some famous historical figures such as Winston Churchill, Thomas Edison and General Patton. And oh yes, a certain “speculative writer, the ‘Year Million Man’ essayist…”

The next thing Baxter does to promote continuity is to stick to Victorian physics and astronomy and cosmology. His solar system is rigorously that of an 1890s understanding, and akin to the consensus venue beloved by the later writers from Planet Stories: swampy Venus, dying Mars, etc. He also treats the various Martian inventions–heat ray, tripods–with logic and consistency.

Thirdly, Baxter carries forward the themes of the original–Darwinian struggle of lifeforms, advanced cultures versus primitive; the logic and ethics of imperialism; the way that social structures fail under pressure; etc.

Lastly, Baxter uses the conditions prevalent at the end of the Wells book as his inviolable points of extrapolation for the subsequent fourteen years that separate his plot from Wells. Thus we learn that the UK has become a somewhat Orwellian police state under the dictatorship of one General Marvin, who addresses the populace through special radio sets known as “Marvin’s Megaphones.” The rest of the globe, while cognizant of the earlier Martian invasion, is less affected, although a kind of modified Great War has occurred in Europe.

So, with this sturdy framework of character, theme, technology and extrapolation in place, Baxter kicks off his new invasion, a decade and a half after the original. A huge fleet of capsules is seen to be launched from Mars, and their impact points on Earth are plotted. The military has strategies in place to re-fight the last war better, but the Martians have learned to improvise. Their first new tactic is to employ the advance-wave empty capsules as kinetic bombs. Thus they immediately wipe out half the English forces like so many meteor impacts. Then the second wave arrives. From here, it’s death, destruction, distraction and desperation for all.

The events are filtered through Julie’s scrupulous reportage, which is presented as an after-the-fact record or reconstruction, with much foreshadowing that eventually humanity will emerge intact. This strategy, I felt, removed some of the suspense from the tale, but the immediacy and drama of the plot could still be relished, if one put aside the guarantees of some kind of victory. And the surprise nature of that victory remains intact right up to the big reveals. Additionally, Julie will present some of her story from the POV of Frank Jenkins and his companion Verity Bliss. This move was essential to shoehorn in some important events, but taking Julie offstage seemed a bit awkward at first.

But with these quibbles aside, the book is stuffed with potent action scenes, tangible human relationships, epic incidents of devastation and despair, and surreal moments such as the feeding chamber in the Great Redoubt of the Martians. Those aliens come off as less cipherish than they do in Wells, with rational reasons for all their actions. The book never ventures into the more van Vogtian realms that I seem to recall The Time Ships did, but that is totally in keeping with the mimetic fidelity of Wells’s original.

Part of the “charm,” if you will, of such apocalyptic books as this one is the alluring overturn of mankind and the vaunted civilized works of our species. We all secretly revel in imagery of our boring civilized lives tossed into the trash heap where they belong, and Baxter satisfies that perverse urge perfectly.

But if you looked closer things were far from ordinary.

There was no other traffic to be seen on the road along which we sped, for a start. Here and there one would see wreckage —cars driven off the road and abandoned to rust. The most startling sight of that sort, which we saw from a level crossing, was a crashed train. It lay along the line that had carried it; passenger coaches were smashed to matchwood, and freight coaches lay on their backs, with their rusting wheels in the air, like tremendous cockroaches, upended. It was not the train’s destruction that affected me so much as the fact that it had never been cleared way.

A little later we passed at speed through an area that looked, from afar, as if it had been burned out, for a black dust, like soot, lay over everything: the road itself, the houses, the fields. I would learn from a grim-faced Frank that this was the aftermath of a Black Smoke attack.

Now perhaps the most intriguing accomplishment of this book involves something that it is not. It is definitely not steampunk. Steampunk is a postmodern style of knowingness and hindsight and revisionism, sometimes devolving to sheer farce, camp and snark. One could write a steampunk sequel to TWotW, but that is not what Baxter has done. He has written a “cutting-edge” Victorian SF novel as authentically as a person can compose such a thing in the year 2017. And for this, he is to be honored, as he valiantly fills in large part the vacant shoes of his literary grandfather.