Graham Sleight’s Yesterday’s Tomorrows: Roger Zelazny

A lot of the problems particular to SF can be thought of as problems of register. SF stories have to shift from naturalistic dialogue to infodumping to (sometimes) the high-flown language of transcendence. The argument against ‘‘As you know, Bob…’’ dialogue is not that it’s wrong per se, but that it doesn’t fit with what dialogue normally does. The challenge of writing an SF story is about making these different registers work together without the clunk of changing registers. It’s not surprising, then, that the default of SF style has been a kind of journalistic transparency. Journalism, after all, can shift from reporting what’s said to delivering big chunks of information. But it’s also a style that adheres strictly to the factual, and so has real problems when it has other tasks to achieve – to evoke, to suggest, or to hint.

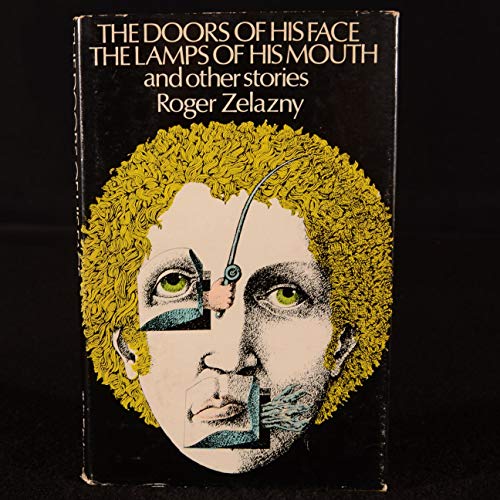

Roger Zelazny’s writing gives an impression of having solved all these problems, of having integrated all the jobs of an SF writer into one consistent voice. He began publishing SF in 1962, and by the late ’60s was one of the dominant figures of the field. NESFA Press have been publishing his complete short fiction in six volumes, assembled to their usual meticulous standards. In this case, though, I’d suggest it’s worth trying to track down one of the collections published in his lifetime, such as The Doors of His Face, The Lamps of His Mouth, and Other Stories. These collections are both a more manageable way to get a sense of his work, and are arranged very artfully.

My favorite of the stories in the collection is ‘‘A Rose for Ecclesiastes’’. It embodies many of his enduring preoccupations, such as the work of art and the work of myth. The protagonist, Gallinger, is a poet and translator working on a human-inhabited Mars where he also has to wrestle with the native culture and literature:

The High and Low Tongues were not so dissimilar as they had first seemed. I had enough of the one to get me through the murkier parts of the other. I had the grammar and all the common irregular verbs down cold: the dictionary I was constructing grew by the day, like a tulip, and would bloom shortly.

Now was the time to tax my ingenuity, to really drive the lessons home. I had purposely refrained from plunging into the major texts until I could do justice to them. I had been reading minor commentaries, bits of verse, fragments of history, and one thing had impressed me strongly in all that I had read.

They wrote about concrete things: rock, sand, water, winds, and the tenor couched within these elemental symbols was fiercely pessimistic. It reminded me of some Buddhist texts, but even more so. I realized from my recent recherches, it was like parts of the old testament. Specifically, it reminded me of the Book of Ecclesiastes.

Gallinger’s response to Martian civilisation is, therefore, first and foremost a response to its culture and its affect. He begins to argue with it, to see the limitations of the pessimism embodied in Ecclesiastes. He dreams of bringing something new to this culture: the optimism and the beauty embodied in the idea of the rose, but roses can also be sick, as William Blake said. The passage I’ve quoted neatly encapsulates several things about Zelazny’s narrative voice. It is, for a start, knowing, informal, sophisticated. It happily mixes the informal (‘‘murkier,’’ ‘‘down cold’’) with the businesslike and the borderline-pretension of dropping in a word like recherches.

‘‘A Rose for Ecclesiastes’’ is also very much a story of personal discovery, of Gallinger finding out what he thinks. As he engages and argues more deeply with the Martian culture, he begins to think that he may have a role in it himself. In the end, his hubris leads to tragedy, and the story ends on a very gloomy note. But what one remembers is the encompassing richness of its voice, the sense that Gallinger really is trying to take in a whole alien culture.

For all Zelazny’s sophistication and skill, it’s also clear that much of his underlying material is not new. The title story of the collection, about a monster-hunt on Venus, could have been told in a different voice 40 years before – but the voice is the crucial thing. ‘‘Devil Car’’ embodies a fascination with the kinetic thrill of cars and of speed – an enduring idea for Zelazny. ‘‘Love is an Imaginary Number’’ is another story that wrestles with myth – the reader’s task being to figure out which myth is being retold, and how it is being revised. Some of the stories in the collection, like ‘‘Lucifer’’ and ‘‘Divine Madness’’, are relatively brief squibs, but Zelazny’s authority never falters, and nor does the charisma of his voice.

Myth was a central preoccupation of Zelazny’s career. Many of his novels deal with it very directly; to my mind, Lord of Light is the most successful. It’s a story of gods incarnate, reenacting the stories and battles that constitute their deepest selves. The setting is a far-future world where Earth is a distant memory, but where the personas of the Hindu and Buddhist pantheon have been made manifest. The protagonist Mahasamatman – better known as Sam – bounces back and forth across this world in seven chapters, each comprising a distinct and more or less self-contained adventure. The tone is much more formal than in many of Zelazny’s stories:

It is said, also, that the phantom cat who killed them was not the first, or the second, to attempt this thing. Several tigers died beneath the Bright Spear, which passed into them, withdrew itself, vibrated itself clean of gore and returned then to the hand of its thrower. Tak of the Bright Spear himself fell, however, struck in the head by a chair thrown by Lord Ganesha, who had entered silently into the room at his back. It is said by some that the Bright Spear was destroyed by Lord Agni, but others say that it was cast beyond Worldsend by Lady Maya.

The key phrase there, it seems to me, is the repeated ‘‘It is said,’’ with its foregrounding of the fact that this is a story embedded within the story – and, moreover, a story that can be told in multiple different ways. The capitalisation and the odd phrasings such as ‘‘this thing’’ all contribute to the sense that this is a very different kind of story from most SF. The story can be justified as science fiction, via technological notions of ‘‘biofeedback,’’ but its affect is surely closer to fantasy. That’s reinforced by the sense that there is a rigid hierarchy of deities here. (To disclose what kind of nerd I am: I found myself mapping the stories onto the mechanics and spells of a high-level Dungeons and Dragons campaign – even though the book predates the game’s publication by several years.)

It has to be said, also, that the kinds of myth Zelazny draws on are treated in ways that are very much of their time. 1967 was also the year of Sergeant Pepper and the Beatles’ retreat to an Indian ashram. It was, more generally a period when the rich nations of the West found their countercultures reaching out to systems such as Indian religion for a kind of purity or authenticity that they could not find more nearby, so some of the vaguer assertions about oneness with the universe might now seem rather dated. And these days, we might well be a little more questioning when a US writer borrows (or appropriates) the myths of another culture for his own ends – but there’s no doubting the clarity and conviction of Zelazny’s reimagining of these stories. Lord of Light is, at its best, thrilling and effortlessly effective at evoking the gods it depicts.

Later in his career, Zelazny became a writer primarily – maybe even solely – known for his fantasy. His Amber sequence comprised a core of ten novels, in two chunks of five. The first set, comprising Nine Princes in Amber (1970), The Guns of Avalon (1972), Sign of the Unicorn (1975), The Hand of Oberon (1976), and The Courts of Chaos (1978), is assembled as The Chronicles of Amber. Alternatively, one can buy all ten as The Great Book of Amber – but, to my taste, the first five are the strongest books. They centre around Corwin, heir to the throne of Amber, which in many ways is a typical fantasyland. However, Zelazny places one axiom at the root of his story: that this is a multiverse tale in which Amber is the ‘‘reallest’’ reality. So other worlds, including ours – in which Corwin awakes at the start of the first book – are just shadows of Amber. This emerges slowly through the first book, as does a dynastic story. Corwin’s father Oberon has disappeared, and his brother Eric has usurped the throne.

The multiverse setting allows Zelazny, even more than usual, to be casually allusive to myths and stories he happens to be fond of. Eric’s coup is inevitably reminiscent of Hamlet; more pervasively, ideas of the Tarot cards as shapers of the story are seen throughout. There’s a kind of amused knowingness about Zelazny’s use of all these myths. One can imagine the Amber sequence potentially continuing forever, stories being used to make sense of stories.

As the sequence goes on, we find out more about the metaphysics of Amber – in particular about another world known as the Courts of Chaos that seems to be equally central to reality. The Courts gain in prominence in later books, and so does the malleability of reality. So, on a quest towards the end of the fifth book, Corwin is assailed by visions of a moment in Earth’s history: ‘‘Why should I suddenly remember 1905 and Paris on the shadow Earth, except that I was very happy that year and I might, reflexively, have sought an antidote for the present? Yes…’’ This isn’t quite a case of stories being used to make sense of stories – the evocation of Paris is more like a leitmotif in a Wagnerian music-drama, a gravity-well that the story can circle and approach when it needs to. It’s no coincidence, I think, that the central mapping of Amber to all its subsidiary realities is known as the Pattern. Zelazny’s central concern is patterns, and how they can be used to inform stories. Myths are one kind of story, memories are another, and the Tarot is another.

It has to be said that, compared to a work like George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire, the Amber sequence can seem a little safe, a little controlled. Because in this world reality is so flexible, there’s always the sense that bad events might not count. In Martin, you know that death is real and permanent. In Zelazny, it might instead signify a shift to another kind of being. (One of his last short stories, ‘‘The Three Descents of Jeremy Baker’’, is about death-as-transformation three times over.) Indeed, Zelazny’s work as a whole doesn’t often have a sense of risk. He’s always enormously in control of his material, of the registers, of the flow of the story. He is, as a result, great fun to read: the sort of author you feel is always flattering you. To put it another way, perhaps more than any other SF/F author, he’s interested in story as synthesis. The question – the risk he takes – is whether you will be too.

Another fine mini-essay, Graham! Like all your Locus essays, it’s astute, deftly-expressed, enjoyably compressed. Good stuff! I hope these pieces might form the core of a future book.