Russell Letson Reviews The Final Frontier, edited by Neil Clarke

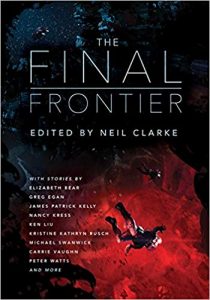

The Final Frontier, Neil Clarke, ed. (Night Shade 978-1-59780-939-9, $17.99, 579 pp, tp) July 2018. Cover by Fred Gambino.

The Final Frontier, Neil Clarke, ed. (Night Shade 978-1-59780-939-9, $17.99, 579 pp, tp) July 2018. Cover by Fred Gambino.

Last month I recommended Jonathan Strahan’s original anthology, Infinity’s End, as a window into what SF is up to Right This Minute (or up to the minutes the stories were completed, anyway). At the same time I was also reading Neil Clarke’s recent-retrospective The Final Frontier, which samples work that first appeared between 2004 and 2016. The 21 stories gathered there also take a long-futureward view, though the book’s subtitle emphasizes broad topical categories rather than temporal expanse: “Stories of Exploring Space, Colonizing the Universe, and First Contact.”

Is there something for everyone here? A genuinely representative sample of current SF? The contents page shows a mix of veterans (Michael Bishop, Greg Egan, James Patrick Kelly, Nancy Kress, Kristine Kathryn Rusch, Michael Swanwick) and writers who have emerged over the last decade or less (Seth Dickinson, Ken Liu, Julie Novakova, An Owomoyela, Genevieve Valentine). There is certainly a decent range of material, including iterations of classic – or at least persistent – modes, tropes, themes, treatments, ideas, and implementations-of-possibilities for star travel and associated topics: First Contact and other alien encounters, virtualized and/or post-human crews, seedships, shipwrecks, spaceborne disasters, maroonings, rescue missions, escapes, and salvations in a variety of exotic environments.

The variety of motifs tempts me to start drawing a map of the 21st-century-SF genre space, but the topology is all folds and wrinkles and overlaps and odd contiguities, and the territory is not flat but n-dimensional, so I keep running into myself coming around corners. (There’s a Venn diagram metaphor that might apply, but it requires spheres and tesseracts and gives me a headache when I try to visualize it.) If the following account is disjointed, it’s because the stories don’t fall into a tidy order – they mix and match and bounce off each other, in a miniature version of the many-voiced conversation that is the SF genre. (Ah, there’s the metaphor I was scrabbling after!)

Seven of the selections run to novelette or novella length, and two of those are parts of larger projects. Kristine Kathryn Rusch’s “Diving into the Wreck” is the first section of what became a multivolume book series set in a future so distant that it has forgotten (or hidden) huge swathes of its own history. Here, however, that is background to a foreground emphasizing the very physical dangers of crawling around ruined spacecraft in vacuum and zero gee (“the sharp edges are everywhere”) filled with lethally enigmatic ancient technologies. Peter Watts’s “The Island” is the introductory entry to his Sunflowers sequence, set millions of years into a project to thread the galaxy with a faster-than-light freeway of wormholes, and featuring encounters with beings right out of Olaf Stapledon (or maybe Lovecraft), if sometimes with longer, sharper teeth. Some aspects of this episode – the strained relationship between the crew and the ship’s guiding intelligence – snap into better focus when fitted together with its series-mates, but its particular problems – physical, metaphysical, moral, and alien-diplomatic – are pretty compelling all by themselves.

Speaking of really long voyages in starships with minds of their own, James Patrick Kelly’s “The Wreck of the Godspeed” could be a second cousin of the Watts and distant kin to Nancy Kress’s “Shiva in Shadow,” but then I’d have to figure where to fit in its treatment of metaphysics and its transmogrified amateur adaptation of The Tempest. The Kress is as much about relationships, personal and organizational, as the astrophysics that provides the hazardous hard-SF environment for its exploratory expedition to the neighborhood of the galaxy’s central black hole. But the external hazards are not the most dangerous ones.

Greg Egan’s “Glory” is a common-background companion to his earlier “Riding the Crocodile” but, more significantly, it’s also part of a larger family of Eaganian motifs and tropes dealing with the explorations of intelligences, embodied or virtualized as needed, driven by curiosity and love of knowledge for its own sake as much as by any other urge or desire. It has a distant cousin in Julie Novakova’s “The Symphony of Ice and Dust,” which packs two stories of exploration and alien discovery, eleven thousand years apart, into one frame.

Despite the volume’s ringing title, it’s hardly all triumphalism Out There, and sometimes we’re not exploring so much as fleeing. In Carter Scholz’s somber “Gypsy”, despite the heroic efforts of desperate visionaries, the final frontier is actually a closed door, and not so very far off, either. In Genevieve Valentine’s “Seeing” and Ken Liu’s “Mono no aware”, humans have taken to space as refugees, with breakdown and self-sacrifice as central features. Star-travel can take a toll on pilots or navigators in Carrie Vaughn’s “The Mind is Its Own Place” and An Owomoyela’s “Travelling into Nothing”. The compelling story of Gwyneth Jones’ “The Voyage Out” lurks in the glimpses of the nightmarish Earth society that is exiling its involuntary colonists to a maybe-fictional First Landfall planet. Tobias S. Buckell’s “A Jar of Goodwill” puts humankind in the subaltern position of a people dominated by interstellar bullies that are not only commercial imperialists but, in a kind of 1950s-Galaxy comic-inferno scenario, patent trolls – “No one had expected aliens to demand royalty payments for technology usage that had been independently discovered by us….”

And so it goes, with motifs and ideas and associations twining and recombining and interacting in interesting ways. In “Three Bodies at Mitanni”, Seth Dickinson presents a classic dramatized debate or thought experiment as a crew of three judge-and-jury colony evaluators face a moral dilemma: what to do about colonists who have re-engineered themselves for utter altruism in a way that would allow them to outperform standard humankind, should they spread through the galaxy. Are they a malignancy whose cure is genocide? There are also variations on the get-out-of-a-pickle problem story: Jack Skillingstead’s “Rescue Mission” (rescue from aliens); Elizabeth Bear’s “The Deeps of the Sky” (rescue by aliens); Michael Swanwick’s “Slow Life” (rescue by aliens, with some nifty exotic chemistry thrown in). Michael Bishop’s novelette “Twenty Lights to ‘The Land of Snow”‘ piles on the mix-and-match elements: a compressed coming-of-age story about a girl Dalai Lama-designate on a Tibetan Buddhist colony starship. It has one of my favorite lines, which also suggests its tone: “One of the Brandenburg Concertos swells, its sitars and yak bells flourishing.”

“Permanent Fatal Errors” by Jay Lake is full of sly digs at Heinleinian hyperindividualists. Sean McMullen’s part-puzzle, part-courtroom-drama “The Firewall and the Door” had me thinking of Jack McDevitt, both for its familiar future domesticity and its portrait of a culture that has turned away from space exploration for half-ethical and half-budgetary reasons. Vandana Singh’s “Sailing the Antarsa”, with its notions of cross-species kinship and “altmatter” wings catching interstellar currents, had me thinking of Le Guin, Nancy Kress, and David Lindsay’s A Voyage to Arcturus, though whether that last one represents an actual intersection or some idiosyncratic neurological accident I can’t say.

I end pretty much where I did with Infinity’s End, with a sense that there is as much continuity as novelty in this century’s science fiction, and that familiarity is breeding not contempt but ingenuity and second looks worth taking. There’s life in the old genre yet.

Russell Letson, Contributing Editor, is a not-quite-retired freelance writer living in St. Cloud, Minnesota. He has been loitering around the SF world since childhood and been writing about it since his long-ago grad school days. In between, he published a good bit of business-technology and music journalism. He is still working on a book about Hawaiian slack key guitar.

This review and more like it in the October 2018 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.