The Knack of the Puppet People: A Review of Downsizing

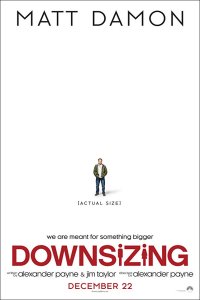

An introductory disclosure: when I was in graduate school, I became the friend, and occasional roommate, of Jim Taylor’s older brother Doug Taylor, and I met and talked with Jim a few times when he was a student at Pomona College. I particularly remember a final conversation when Jim reported that, after graduating, he had moved to Los Angeles to pursue, so far unsuccessfully, a career as a Hollywood screenwriter. Little did I anticipate that I would next observe him on television at the 2005 Academy Awards, accepting (with Alexander Payne) an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay for Sideways (2004). Around that time I also read an article in an Omaha newspaper about Jim visiting Omaha to scout locations for an upcoming “sci-fi film” he was working on that was based on an idea from his brother Doug. Now, finally, that film, called Downsizing, has appeared as the latest product of the Payne-Taylor partnership, with Doug credited as an associate producer and making a cameo appearance in an early scene as a scientist gaping in awe at miniaturized people.

An introductory disclosure: when I was in graduate school, I became the friend, and occasional roommate, of Jim Taylor’s older brother Doug Taylor, and I met and talked with Jim a few times when he was a student at Pomona College. I particularly remember a final conversation when Jim reported that, after graduating, he had moved to Los Angeles to pursue, so far unsuccessfully, a career as a Hollywood screenwriter. Little did I anticipate that I would next observe him on television at the 2005 Academy Awards, accepting (with Alexander Payne) an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay for Sideways (2004). Around that time I also read an article in an Omaha newspaper about Jim visiting Omaha to scout locations for an upcoming “sci-fi film” he was working on that was based on an idea from his brother Doug. Now, finally, that film, called Downsizing, has appeared as the latest product of the Payne-Taylor partnership, with Doug credited as an associate producer and making a cameo appearance in an early scene as a scientist gaping in awe at miniaturized people.

Though I’ve had little contact with Doug in recent decades, some people who don’t know me (and my habit of criticizing colleagues in print) might suspect that this personal connection would make me overly inclined to praise this film; in fact, I entered the theatre sadly anticipating that, the next day, I would be obliged to honestly report that I absolutely despised it. Instead, I was enjoyably fascinated by this thoughtful, consistently surprising film, which completely defied all my expectations.

When filmmakers unfamiliar with science fiction venture into the genre, they tend to present their amazing innovation as a dangerous disruption of the social order that must be expunged in order to restore the status quo. Thus, when Norwegian scientist Jorgen Asbjørnsen (Rolf Lassgård) perfects a method for shrinking people and animals to a tiny size, and proposes this as a way to reduce humanity’s harmful impact on the environment, I was sure that there had to be a catch. Yes, initially, numerous people might eagerly seek to miniaturize themselves to live in tiny communities, attracted by the opportunity to live in the mansions, and have all the luxuries, that they now could easily afford because they were so small, but I kept waiting for some horrible side effect to materialize, leading them to regret their decision and forcing scientists to devise a way to reverse the process and restore everybody to normal size. (Indeed, when Asbjørnsen, rushing to announce his breakthrough, passes a rack of magazines, with one featuring a cover story about the Titanic, one might view that as a harbinger of disasters to come.) However, this crisis never occurs, as the process proves to provide a genuinely utopian existence for most of the small people; a daunting problem does eventually emerge, but it has nothing to do with their diminished stature. In this way, Payne and Taylor’s screenplay admirably reflects the attitude of the science fiction writer, who does not abhor new discoveries but rather seeks to explore how they would affect society when integrated into everyday life.

Observing Paul Safranek (Matt Damon) adjust to his new life in the idyllic community of Leisureland, we gradually learn about the benefits, and drawbacks, of being five inches tall. As Leisureland employee (Niecy Nash) explains, the Safraneks’ total assets – $152,000 – will be equivalent to 12.5 million dollars in Leisureland, since tiny things are much cheaper, effectively making them millionaires; one character says, “It’s like winning the lottery every day.” During a contrived promotional presentation, Jeff Lonowski (Neil Patrick Harris) feigns unhappiness because his wife Laura (Laura Dern) has wasted 83 dollars buying jewelry with diamonds about the size of dust specks. With no need to work, small people can spend all their time visiting recreational facilities, going to parties, and taking extended vacations; the dome covering Leisureland that protects residents from birds and insects also provides consistently “nice weather”; and with no reasons to break any laws, there is “zero crime” in Leisureland. When they fly in airplanes with special sections just for them, “Every seat is first class.” Since they are constantly surrounded by people and objects of their own size, they don’t have to experience the pain of Grant Williams’s Scott Carey in The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957), feeling tiny and out of place in a massive world, though occasional encounters with normal people may be disturbing; a woman Safranek has dinner with describes being with her family in a restaurant and lamenting that “Big people look at us like freaks.” Only a few amenities from their former world are now unavailable, as Safranek, unable to obtain the herb chervil for a recipe, has to use dill instead. And there is the suggestion that, just as the small mammals remained alive when the dinosaurs died, small people may be better suited to survive a future catastrophe.

As for the downsides of downsizing, small people are not universally liked by normal people, as one man in a bar complains that “They’re not contributing to the economy” with their miniscule expenditures and suggests that they only deserve a fraction of a vote. Safranek’s wife Audrey (Kristen Wiig) regrets that, as a miniaturized person, she will be effectively separated from family members and friends. Though some small people like Safranek do take jobs, apparently to have something to do, Safranek’s neighbor Dusan Mirkovic (Christoph Waltz) complains that “Small people are lazy – no one wants to work”; like other apparent utopias, Leisureland provides individuals with no incentives to make the world a better place, or even improve their own lives. There are worries about miniaturized terrorists, and a talking head on television anticipates that the process will inevitably be employed to oppress minorities; in fact, we later encounter a Vietnamese dissident, Ngoc Lan Tran (Hong Chau), who was forcibly miniaturized by her government and obliged to flee the country with other dissidents in a shipped television box.

Not everybody in Leisureland is living the good life; as one character notes, when you’ve been earning a decent income, “You get small, you’re rich,” but “When you’re poor, then you’re just small.” After Safranek meets Ngoc, who now works as a household cleaner for wealthy residents like Mirkovic, viewers are introduced to the Leisureland slums, a converted trailer filled with trashy apartments mostly inhabited by Hispanics and other minorities; one poor woman’s husband was killed when a slapdash miniaturizer in Mexico failed to remove his dental work and made his tiny head explode. Thus, miniaturization has not eliminated the problem of social inequality, as illustrated by other contrasts between the lifestyles of the upper class and the underclass. The people that Safranek associates with seemingly feel no need for the consolation of religion, as one never observes, or hears about, any churches in Leisureland; Ngoc and her friends attend a church service in a ramshackle room to “pray Jesus.” When he needs to travel, Safranek uses the rental cars available for a nominal fee; Ngoc takes the bus. And wealthy residents with many other things to do rarely if ever look at their computers or watch television; but after she gets home and checks on her sick friend, Ngoc immediately starts looking at her tablet, and the other residents of her building are constantly entertained by a huge television showing a Cantinflas movie and a Mexican game show.

Further, while the increasing numbers of small people must be benefiting the environment, they are still living in a world beset with problems. Safranek’s mother (Jayne Houdyshell) bemoans the fact that scientists can shrink people and “fly to Mars,” but they can’t cure her fibromyalgia; when she concludes, “I’m in pain,” Safranek replies, “Lots of people are in pain – in all sorts of ways”; terrorists remain a constant threat; there are concerns about the potentially disastrous effects of methane gas being released from the Antarctic ice; and indicating that Payne and Taylor live in southern California, the rolling text under one television news program reports that “Brush fires in western U.S.” have burned a vast area and “destroyed over 100 homes.”

Finally, albeit in an understated way, Safranek faces the same problem as The Incredible Shrinking Man: finding a purpose for his life in a world that defines him as small and inconsequential. The man is not happy; as Mirkovic observes, “You dance, you laugh, but inside you cry.” He has taken a menial job in an effort to feel useful, though he obviously does not find it fulfilling to deal with Lands’ End customers who can’t decide what color they want. For Scott Carey, the answer is his vague but memorable conclusion that “All this vast majesty of creation, it had to mean something. And then I meant something, too. Yes, smaller than the smallest, I meant something, too.” Safranek gets his answer from Ngoc: to make his life meaningful, he must help other, less fortunate people. When the former occupational therapist volunteers to adjust Ngoc’s faulty prosthetic leg, she instructs him to accompany her and ease the pain of her dying friend Gladys (Rose Bianco), and after some additional prodding, he is also assisting her in cleaning houses, bringing food to poor neighbors, and ministering to other sick people not being served by the Leisureland clinic. Still seeking to affirm his identity, he eventually feels driven to make a decision that Ngoc opposes, telling her, “If I don’t do this, who am I?” Her forceful reply – “You are Paul – good man” – argues that his charitable deeds define who he is, a position that he ultimately embraces.

Overall, then, the film argues that, like other technological innovations of the past two centuries, the process of miniaturization will have generally good effects, but some bad effects; when someone tells Safranek that “It’s quite wonderful to be small,” he replies that “It has its plusses and minuses.” And this sound judgment contrasts sharply with the hysterical fears of new inventions that one so frequently observes in other science fiction films. It is hardly surprising that films about miniaturized people regularly depict their situation as a horrible fate – The Incredible Shrinking Man, Dr. Cyclops (1940), Attack of the Puppet People (1958), and so on – or, at best, as a plight to be entertainingly dealt with, as in Honey, I Shrunk the Kids (1989). In a few cases, some individual tiny people have been viewed as helpful, like the superheroes Doll Man, Ant-Man, and the Atom; the heroic spy of the television series World of Giants (1959); and the miniaturized surgeons of Fantastic Voyage (1966). The only specific precedent for this film’s scenario of beneficially shrunken populations is a vaguely remembered story in a children’s comic book, perhaps featuring Mighty Mouse, wherein an alien scientist solves his planet’s overpopulation problem by shrinking all of its inhabitants, while informing them that he has transported them to a planet of giants. One might also mention the miniaturized Kryptonian city of Kandor, long featured in Superman adventures, and while its bottled inhabitants hoped for, and eventually achieved, a return to normal size, subsequent versions of Kandor have had contentedly tiny residents.

Of course, science fiction is traditionally praised for pondering future scientific breakthroughs that might actually occur, and one cannot say that Downsizing is performing that task. Its miniaturization process is vaguely described as “cellular reduction,” dramatically shrinking individual cells and thus entire organisms, and it involves the injection of a drug and brief exposure to some form of radiation. Any physicist or biologist can undoubtedly provide several reasons why this would be impossible; as David Langford wryly notes in the “Miniaturization” entry of the online Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, “Scientific rationales for the process are not easy to construct, since the major obstacles include the basic physics of mass/energy conservation.” Computer scientists might also find it unfeasible to construct a functional smartphone that is 1/3 inch long, which Safranek employs to take a selfie. And I noticed one inconsistency: the first animal successfully miniaturized was a white rat with a full coat of fur; why, then, is it necessary to completely shave human beings when they undergo the process?

Even if science will never be able to make people five inches tall, one could regard this film as a metaphorical depiction of an actual human condition, dwarfism. Like Safranek and his compatriots, little people tend to prefer the company of other little people, often face discrimination from taller people, and sometimes require special equipment proportionate to their size. This film further provokes the thought that little people are indeed beneficial to the planet, since they take up less space and consume fewer resources. And it’s easy to imagine that scientists could devise ways to deliberately induce dwarfism, and a movement could conceivably emerge to encourage people to choose to have smaller children and gradually reduce the size of the human population. The problem is that evolution has driven homo sapiens in the opposite direction, as people have grown taller and taller, for reasons that may be practical (tall people can reach fruit on high branches and see further away) or aesthetic (people have historically preferred tall rulers, like the biblical King Saul, and employers generally hire tall applicants).

The people of Leisureland might also be said to represent another minority group: retired people. While people of all ages have been miniaturized, the small characters viewers spend most of their time with are middle-aged or older, suggesting the connection, and there are similarities in their situations. Like the newly miniaturized, older people may fortuitously discover that they no longer need to work, as they can live on pensions, Social Security, and savings accounts; they often isolate themselves from others by living in special facilities or retirement communities; they devote almost all of their time to leisure activities; and recalling that drunk in the bar, one can say that they are not contributing their fair share to society, arousing resentment from younger people who still must exert some energy to support themselves. The character of Ngoc, then, might be interpreted as a rebuke to all of those indolent geezers, telling them that even if they don’t have to work, they should be working as hard as they can to help the less fortunate people around them. And Safranek’s final action reflects his refusal to withdraw from society, as he chooses to remain an active, altruistic part of his society.

Still, while Ngoc is sometimes indignant with Safranek and others, Downsizing is ultimately a film that refuses to be mad at anybody; refreshingly, it is an involving story without villains, only some characters who make better decisions than others. To be sure, it isn’t a perfect film: as Safranek himself acknowledges at one point, Payne and Taylor’s story hinges upon a few improbable coincidences, and too much time is devoted to depicting the process of miniaturization. But Downsizing remains both a better and wiser film that the two, more acclaimed science fiction films that I have reviewed this month, The Shape of Water (review here) and Star Wars: The Last Jedi (review here), and one hopes that many viewers will make the correct decision to see it.

Directed by Alexander Payne

Written by Alexander Payne and Jim Taylor

Starring Matt Damon, Christoph Waltz, Hong Chau, Kristen Wiig, Rolf Lassgård, Ingjerd Egeberg, Udo Kier, Søren Pilmark, Jayne Houdyshell, Jason Sudeikis, Maribeth Monroe, Neil Patrick Harris, Laura Dern, Niecy Nash, Rose Bianco, and Phil Reeves

Gary Westfahl has published 25 books about science fiction and fantasy, including Science Fiction Quotations: From the Inner Mind to the Outer Limits (2005), The Spacesuit Film: A History, 1918-1969 (2012), A Sense-of-Wonderful Century: Explorations of Science Fiction and Fantasy Films (2012); excerpts from these and his other books are available at his World of Westfahl website. He has also published hundreds of articles, reviews, and contributions to reference books. His most recent books are the three-volume A Day in a Working Life: 300 Trades and Professions through History (2015) and An Alien Abroad: Science Fiction Columns from Interzone (2016), now available from Wildside Press; ; his forthcoming books include Arthur C. Clarke and Bridges to Science Fiction and Fantasy: Outstanding Essays from the J. Lloyd Eaton Conferences.

Actually, Sideways won the Best Adapted Screenplay award; the Best Original Screenplay winner that year was Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. Both very meritorious movies.