|

Interview Thread

<< | >>

| FEBRUARY ISSUE |

-

-

-

-

Sawyer Interview

-

-

-

February Issue Thread

<< | >>

-

Mailing Date:

30 January 2003

|

| LOCUS MAGAZINE |

Indexes to the Magazine:

|

| |

|

|

|

|

THE MAGAZINE OF THE SCIENCE FICTION & FANTASY FIELD

|  |

|

|

|

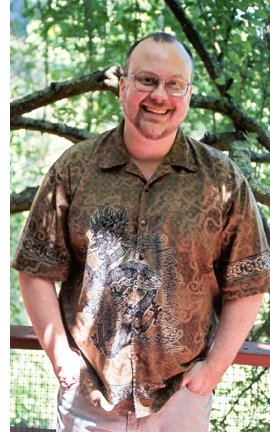

Robert J. Sawyer: Quantum Metaphysics |

February 2003 |

|

Toronto-area SF writer Robert J. Sawyer's first novel, Golden Fleece (1980), won Canada's Aurora Award. It was followed by the "Quintaglio Ascension" trilogy, set on a planet of intelligent dinosaurs, Far-Seer (1992), Fossil Hunter (1993), and Foreigner (1994); then by End of an Era (1994), a time travel novel also concerning dinosaurs. The Terminal Experiment (1995) won both the Aurora Award and SFWA's Nebula Award, and was a Hugo finalist, as were several of Sawyer's subsequent novels, which include Starplex (1996), Frameshift (1997), Illegal Alien (1997), Factoring Humanity (1998), Flashforward (1999), and Calculating God (2000). His most recent novel, Hominids (2002), is first in the "Neanderthal Parallax" trilogy, to be followed by Humans in February '03 and Hybrids in November '03. Sawyer has published one collection of short fiction, Iterations (2002), has edited several anthologies, and is past president of SFWA. He maintains sfwriter.com, one of the most extensive writer's sites on the web.

|

Photo by Charles N. Brown

|

Excerpts from the interview:

“The philosophy of my books has always been rationality as the most prized of human virtues. Far-Seer, Fossil Hunter, and Foreigner took three of the turning points in human intellectual development: the discovery that we weren’t at the center of the universe (the Copernicus, Galilean revolution), that we weren’t the handiwork of God but the product of evolution (the Darwinian revolution), and the discovery that we didn’t even have conscious control over a lot of what we were doing but were driven by unknown subconscious forces (the Freudian revolution). All three of those are interesting for us, but they aren’t crucial. As much as I decry the Creationist movement getting evolution out of the schools, what you believe doesn’t actually affect anything in the world. I wanted to write novels where that was desperately important, and the species would die if they did not learn to understand the subconscious forces that were driving them as a species to violence.

*

“One of the things that’s bothered me over the years is that ‘science’ is a turn-off word for a lot of people, and the science fiction audience is declining. I think a better name for most ambitious science fiction is ‘philosophical fiction.’ It’s fiction about big ideas. Where did we come from? Why are we here? Where are we going? If you ask somebody if they are interested in quantum computing or cloning, they’ll say ‘No.’ But if you ask, ‘Are you interested in what it means to be human, whether there’s life after death, whether there was ever any intelligent intervention in the creation of human beings?’, almost everybody is interested in that. I never downplay the science in my books and I call myself a science fiction writer, but the philosophy and the metaphysics (which I don’t think is a dirty word) are the most interesting to me these days.”

“One of the things that’s bothered me over the years is that ‘science’ is a turn-off word for a lot of people, and the science fiction audience is declining. I think a better name for most ambitious science fiction is ‘philosophical fiction.’ It’s fiction about big ideas. Where did we come from? Why are we here? Where are we going? If you ask somebody if they are interested in quantum computing or cloning, they’ll say ‘No.’ But if you ask, ‘Are you interested in what it means to be human, whether there’s life after death, whether there was ever any intelligent intervention in the creation of human beings?’, almost everybody is interested in that. I never downplay the science in my books and I call myself a science fiction writer, but the philosophy and the metaphysics (which I don’t think is a dirty word) are the most interesting to me these days.”

*

“Science fiction isn’t about trying to predict the future; it’s obviously about the present day. And in the present day you can talk about issues of relevance to people who are alive right now by dressing them in science-fictional garb or by using the metaphysical inquiries that modern physics opens up for you. Quantum physics is the best thing that’s happened to science fiction writers in decades, because it gives us a framework in which we can explore metaphysical and moral questions and still retain science as the underpinning of what we’re talking about. Setting aside whether or not the ‘many worlds’ theory gets definitively disproved, whether or not we will ever prove the value of quantum processes to consciousness, or whether quantum events cause the splitting off of new universes, boy, are they a goldmine for science fiction writers!”

*

“Hominids is the first in my new ‘Neanderthal Parallax’ trilogy. I regard this as the first trilogy I’ve really written as a trilogy. With Far-Seer, when I first set out there wasn’t an overarching vision that was going to span three books. After a dozen books I regard as standalones (the three ‘talking dinosaur’ books notwithstanding), I decided it was time to try something different. I don’t think there have been many successful open-ended series, but you only have to look at something like Asimov’s ‘Foundation’ to know there have been great successes in the trilogy form. I wanted to tackle that, to have a canvas 300,000 words long instead of 100,000. Humans brings the story to another level, and Hybrids brings it to an even greater level. The Neanderthal, Ponter, and the human, Mary, are the main characters in all three books, but each book also has what I believe are satisfactory conclusions so they can be read as standalones. That’s important to the reader.”

The full interview, with biographical profile, is published in the February 2003 issue of Locus Magazine.

|

|

|

|