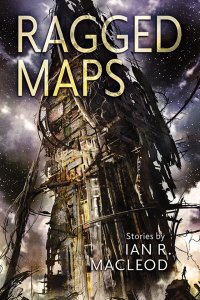

Paul Di Filippo Reviews Ragged Maps by Ian R. MacLeod

Ragged Maps, Ian R. MacLeod (Subterranean 978-1645240938, hardcover, 456pp, $45.00) April 2023

Ragged Maps, Ian R. MacLeod (Subterranean 978-1645240938, hardcover, 456pp, $45.00) April 2023

How best to convey to the uninitiated the contours and pleasures of Ian MacLeod’s fiction? I would start by saying it’s elegant, complex, mysterious, empathetic, melancholy, mystical, and, somehow, quintessentially British; full of startling ideas often verging on the surreal. Then I would say he’s a peer and heir to Aldiss, Peake, Ballard, Priest, and Moorcock. If that’s not enough, I’d toss in Gene Wolfe as a benchmark that MacLeod easily reaches. Given this assessment, MacLeod should be high on the awards ballots and on the shelves of every hardcore SF reader. But I suspect his allure is overshadowed by a mass-culture preference for works that are more shallow and facile, all flash and hype. Too bad. But perhaps this voluminous new collection will serve to dissipate the flavor-of-the-month fog concealing his more-perdurable accomplishments.

A fine “Introduction” by the author lays out succinctly MacLeod’s own assessment of his themes, the main one being time: “forgotten times…the past times of all humanity…,” and time qua time, the medium that keeps everything from happening at once. This clear-eyed self-knowledge is echoed in MacLeod’s modest, chatty afterwords to each story.

Let’s take a gander at each tale.

One of a couple of alternate histories herein, “The Mrs Innocents” charts a world very much like our own, except for a lack of World Wars. But also prevalent is a chain of midwife establishments (under the cognomen seen in the story title) where birthing becomes a sanctified ritual. Our protagonist, journalist Sarah Turnball, finds her pregnant self on the verge of a very large revelation.

“The Wisdom of the Group” strikes me as bordering on pure cyberpunk, as it relates the stochastic doings of a group of investors linked into a gestalt. No character here is very pleasant, and our protagonist gets a woeful comeuppance.

KAT, an orbital AI tasked with curating humanity’s entire cultural legacy, is rightfully besotted with Jane Austen, among other literary treasures. But are such refinements of silicon taste enough to protect its treasures against a posthuman incursion? And will the future depicted in “Ephemera” even care?

A pendant to MacLeod’s two novels about a counterfactual timeline powered by “aether,” “Lamagica” has a distinctly louche, hothouse, Lucius Shepard vibe. In the nasty New World city of Verarica, the dissolute guide Dampier takes on the case of Londoner Clemency Abuthnot, in search of her lost brother. A big aether strike might very well await at the end of the road. But will Dampier dissolve into a neurotic bundle of flaws before then?

“Ouroboros” is a tribute to Arthur C. Clarke, charting a path that leads from computer hacking to pure mysticism. It did not occur to me to compare “Stuff” to the work of Robert Aickman. But once MacLeod cited that genius of weird hauntings in his afterword, I saw the likeness. A daughter must deal with the overstuffed house of her hoarder mother. But when material possessions object to mistreatment, who is safe? This might be the core fictional fleshing out of the tenets of “Resistentialism.”

MacLeod is a dab hand at depicting modern urban society and its technological successors. But pure fable, the land beyond the fields we know? He’s got that covered expertly too. The King’s Adviser in “The God of Nothing” is given a series of impossible tasks. Can an arcane priestess who espouses no particular creed help, like Rumpelstiltskin? And at what cost?

Original to this volume, “Downtime” joins a small but exclusive club of SF that examines future methods of state punishment (Zebrowski’s Brute Orbits, among others). The technique of stripping memories from prisoners is a particularly cruel one, and our hero struggles in a Kafkaesque limbo.

Our second Aickmanesque ghost story is “The Roads”, wherein a young boy gets one last visit from his war-distanced father. “The Memory Artist” follows the struggles of an old woman in the magical city of Ghezirah, as she tries to pursue her art, a bricoleur’s passion. “Of course, as her work became richer and more satisfactory, she herself grew poorer, and acquired fewer commissions…”

A distinctly Boucherian tone (“The Quest for Saint Aquin”), or even Simakian, permeates “Sin Eater”, in which a robot visiting the Vatican finds that ordeals like crucifixion are not reserved just for humans.

“The Visitor from Taured” is a kind of bipartite bildungsroman, charting the parallel fates of Rob and Lita, childhood friends. Rob pursues astrophysics, Lita literature, but they find their careers converging into the node of one grand make-or-break experiment.

Ballard’s city of “Chronopolis” might have survived longer if it had a dedicated servant like “The Chronologist”. Tasked with keeping time running in its proper channels, the mage-like figure is almost undone by the manipulations of a small careless boy.

Far from the traditional merman/mermaid mythic figure of its title, “Selkie” gives us rather a The Man Who Fell to Earth-type tale, in which the ministrations of tender woman are not enough to save a visitor from afar. Lastly, “The Fall of the House of Kepler” richly conflates Poe with a kind of Vancian space opera.

All of these variegated tales are crafted to perfection, not one step amiss in plot or treatment. But it’s really MacLeod’s sensitivity and precision and keen-sightedness, embodied in beautiful prose, that carry one along. Let me conclude my admiration with a sizable excerpt, after which one last note. This is from “The Roads.”

I’d nod, knowing it was just his joke. And he’d stoop to hug me, encased once more in green and brass and buttons. The pattern remained the same over the war years; as much a fact of life as rules of grammar or the rank smell that filled our house when the wind blew east from the tanneries; and each time my father and the cardboard case he brought with him seemed smaller, more sunken, more battered. It was only late in the summer of 1917 when the war, if I had known it, was soon to end, that any of that ever changed.

I was wandering in the town Arboretum. You had to pay to get in in those days but I knew a way through the railings and I was always drawn to the bright scents and colours, the heaped confections of flowers. There was a lake in the centre—deep and dark, a true limestone cavern—and a small mouldering steamer that had plied prettily and pointlessly between one shore and the other before the war.

Each day of that changeable summer was like several seasons in itself. Forced outside to play by our mothers between meals, we had to put up with rain, wind, sunshine, hail. In the Arboretum—watered and warmed, looming in flower scents, jungle fronds, greenish tints of steam—everything was rank and feverish. The lawns were like pondweed. The lake brimmed over. I remember wandering along the paths from the white blaze of the bandstand, ducking the roses that clawed down from their shaded walk, pink-scented, unpruned; sharing in that whole faint air of abandonment that had come over our country at that time.

Just gorgeous.

Before leaving this volume, we should take note that six of these tales, nearly half, first saw the light of day in Asimov’s. Every writer needs an editor who sees and appreciates what the writer is attempting, and MacLeod has found his in the perceptive Sheila Williams, whose guiding invisible hand caresses this fine book.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.