Gary K. Wolfe Reviews The Collected Enchantments by Theodora Goss

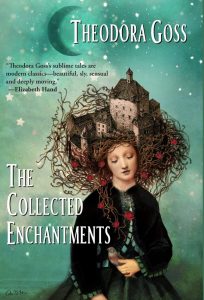

The Collected Enchantments, Theodora Goss (Mythic Delirium 978-1-7326440-7-6, $39.99, 436pp, hc) February 2023.

The Collected Enchantments, Theodora Goss (Mythic Delirium 978-1-7326440-7-6, $39.99, 436pp, hc) February 2023.

2023 is already shaping up as something of a banner year for retrospective short story collections. Last month, I looked at new books from Peter S. Beagle and Catherynne Valente, and generous collections from Howard Waldrop and K.J. Parker are in the offing, as well as posthumous titles from Gene Wolfe, Joanna Russ, and James Tiptree, Jr., (see below). Now we have Theodora Goss’s The Collected Enchantments, an overview of her career in poetry and fiction from her first published story, “The Rose in Twelve Petals” in 2002, to two stories and 13 poems original to this collection. Although probably more widely known for her Athena Club trilogy (beginning with The Strange Case of the Alchemist’s Daughter in 2017) – a shrewd and hugely entertaining feminist reclamation of classic 19th-century horror stories – Goss is equally at home in an older tradition. Like Jane Yolen (who wrote an introduction to Goss’s 2019 collection Snow White Learns Witchcraft), Terri Windling (to whom that book was dedicated), Delia Sherman, Ellen Kushner, Patricia A. McKillip, and Sylvia Townsend Warner, she brings a deep, almost scholarly understanding of folk materials with a sharp and at times playful way of reinventing them. For Goss, fairy tales are less a set of texts than a language she’s become fluent in; sometimes she doesn’t even bother to explain which tale she’s riffing on, as with poems that subtly invoke classics like The Goose Girl, Fitcher’s Bird, or Melusine. Add to this the influence of Ursula K. Le Guin (which expresses itself in somewhat different ways) and Goss’s own experience as a childhood immigrant from Hungary, and the result is a lyrical, resonant voice and a vision not quite like anyone else’s.

One of Goss’s characteristic techniques is simply shifting perspective. That stunning first story, “The Rose in Twelve Petals”, revisits Sleeping Beauty from no fewer than twelve viewpoints, including not only secondary characters, but the hound, the tower, and the spinning wheel itself. Two poems, “The Cinder Girl Burns Brightly” and “The Stepsister’s Tale”, reimagine Cinderella from the points of view not only of the stepsister who mutilates her foot to fit the slipper (and later becomes a podiatrist), but from the fire in the hearth. An aging Snow White inherits her mother’s mirror but seeks a new role for herself in “Snow White Learns Witchcraft”, worries about aging in “Mirror, Mirror”, and, after becoming queen, worries about her own daughter in “How to Become a Witch-Queen” (which is also organized in titled sections that call attention to often-overlooked elements of the tale). Goss’s version of Red Riding Hood almost edges into Angela Carter territory in “Snow, Blood, Fur”, in which Rosie, after dispatching the wolf with a rifle, secretly feels empowered by wearing the wolf pelt. The speaker in the poem “Girl, Wolf, Woods” sometimes identifies with the girl, sometimes with the wolf, and sometimes just with the woods. “That is not how the story goes, you insist,” says the speaker, sounding like Goss talking directly to us. “But that is how I prefer to tell it.”

Another favorite technique involves setting her tales and poems in a liminal space that doesn’t fully segregate fairyland from our own world. Red gets engaged to an accountant, Sleeping Beauty’s prince shows up driving a bulldozer, Rumpelstiltskin pollutes Germany and France with his industrial mills. One of the strongest stories, “Red as Blood and White as Bone”, begins with its poor orphan narrator declaring, “This is a good way to start a fairy tale,” goes on to invoke Fair Ladies, the Old Woman of the Forest, and magical wolves, but ends with that orphan narrator, now adult, joining the Resistance in Nazi-occupied Europe. This story is also one that reflects that echo of Le Guin I mentioned earlier. It’s set in Sylvania, an imaginary middle European country that is Goss’s version of Le Guin’s Orsinia. “Princess Lucinda and the Hound of the Moon” begins purely in fairytale land, with Lucinda discovered as a foundling by the childless queen of Sylvania and the titular hound setting up a series of tests to find the real daughter of the moon, but by the end, WWI has come and Lucinda has won a Nobel Prize in astrophysics. In “Fair Ladies”, a frustrated father takes his dissolute son in hand to set up a respectable marriage, but the youth finds himself involved with the “fair ladies,” seductive forest sprites who have lived in Sylvania since Roman times. As with some of Le Guin’s Orsinian tales, it works well as a mainstream story of family tensions, but alludes to a deep history of the imaginary nation. The forests of Sylvania also figure prominently in “Saint Orsola and the Poet”, a lyrical fantasy of a poet’s origin whose title even suggests Le Guin.

Goss seems equally at home in far less exotic settings, such as the small town of Ashton, North Carolina, which figures in such stories as “The Wings of Meister Wilhelm”, “Lessons with Miss Grey”, and “Lily, with Clouds”. But here the magic is imported, or just out of reach. Miss Grey disrupts the social lives of young women in Ashton by setting up a school for witches, while Meister Wilhelm is a brilliant musician reduced to giving lessons in the small town, while dreaming of joining a mystical arts utopia called Orillion. Lily, a rather hapless prodigal returning to Ashton as she is dying from cancer, finds herself transfigured in the paintings of a famous artist with whom she was involved. It’s not the only tale in which art serves as a kind of redemption. One of my favorites, “Pip and the Fairies”, describes the daughter of a famous children’s book writer who, like the real-life Christopher Robin Milne, has to live with her reputation as a model for her mom’s fiction, but who finds a way of coming to terms with it that is both magical and thoroughly practical. She can also evoke, sometimes almost painfully, the challenges of graduate school, as in one of the skillfully interwoven narrative threads of her World Fantasy-winning “Singing of Mount Abora”, or in “A Country Called Winter”, which begins as a fitful academic romance involving a graduate student who had immigrated from that fictional country as a child, much like Goss herself. The voice is utterly convincing, even as the story whiplashes back into fairytale territory in an unexpected twist. But it’s also evidence that Goss’s tonal and thematic range extends well beyond the fairy realms that she deconstructs so shrewdly in most of these tales and poems: in its way, Ashton, NC is as fascinating as Sylvania, and The Collected Enchantments leaves us wanting more of both.

Gary K. Wolfe is Emeritus Professor of Humanities at Roosevelt University and a reviewer for Locus magazine since 1991. His reviews have been collected in Soundings (BSFA Award 2006; Hugo nominee), Bearings (Hugo nominee 2011), and Sightings (2011), and his Evaporating Genres: Essays on Fantastic Literature (Wesleyan) received the Locus Award in 2012. Earlier books include The Known and the Unknown: The Iconography of Science Fiction (Eaton Award, 1981), Harlan Ellison: The Edge of Forever (with Ellen Weil, 2002), and David Lindsay (1982). For the Library of America, he edited American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s in 2012, with a similar set for the 1960s forthcoming. He has received the Pilgrim Award from the Science Fiction Research Association, the Distinguished Scholarship Award from the International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts, and a Special World Fantasy Award for criticism. His 24-lecture series How Great Science Fiction Works appeared from The Great Courses in 2016. He has received six Hugo nominations, two for his reviews collections and four for The Coode Street Podcast, which he has co-hosted with Jonathan Strahan for more than 300 episodes. He lives in Chicago.

This review and more like it in the April 2023 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.