Gary K. Wolfe Reviews Kid Wolf and Kraken Boy by Sam J. Miller

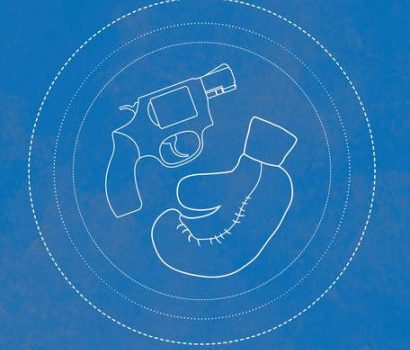

Kid Wolf and Kraken Boy, Sam J. Miller (Solaris 978-1-78618-731-4, 176pp, $15.99, tp) July 2022.

Kid Wolf and Kraken Boy, Sam J. Miller (Solaris 978-1-78618-731-4, 176pp, $15.99, tp) July 2022.

Jonathan Carroll isn’t the only one who’s been thinking about magical tattoos lately, and in fact it’s a fairly venerable tradition. But I think Sam J. Miller has probably carved out his own niche with Kid Wolf and Kraken Boy, which may sound like an unrealized Robert Rodriguez film project, but in fact is an alt-history Roaring Twenties New York gangster boxing labor-rights queer romance – with, of course, those magic tattoos. In short, there’s a good deal going on in a relatively short novella, ranging from a meticulously researched account of the actual world of boxing in 1929 to the effects of anti-Semitism, racism, homophobia, and strike-breaking, even to bits of Hollywood history. Shark Boy and Lava Girl never dreamed of anything like this.

Narrated in alternate chapters by the two title characters, the tale begins with each recalling their meeting from the perspective of decades later, in the 1980s. Solomon Wolffe, the boxer, has been rechristened Kid Wolf by the promoter Hinky Friedman, who has improbably overcome both sexism and anti-Semitism to become a major player in the brutal and corrupt world of New York boxing. Teitelstam, the amateur tattooist, is also recruited by Friedman, who has learned of the unusual mystical power of his work, and who wants him to develop tattoos that will assist Kid Wolf in the ring. Teitelstam’s nickname Kraken Boy is later bestowed on him by Kid Wolf, with whom he finds an immediate attraction that turns into a fully realized, and at times quite moving, love story. We also get some early hints that the historical perspective they are narrating from is not quite our own; we’re told that Meryl Streep has played Hinky Friedman in the movies, and that ‘‘Chisholm’’ is president in the 1980s – presumably Shirley Chisholm, who actually did run in the 1970s. Further hints suggest they are now living in a kind of post-capitalist society, though many of the details of his alternate history are saved for much later in the story.

Miller’s work as a community organizer has often informed his fiction, if not always on the surface, and it’s equally apparent here, with the conviction that even a world as corrupt as the boxing game in the 1920s can be changed for the better, and that the power of organizing can be formidable. His fascination with boxing itself – a fascination he shares with writers as diverse as Ring Lardner, Rod Serling, and Joyce Carol Oates – is something new with Kid Wolf and Kraken Boy, and his historical references to actual boxers of the era give the tale a gritty, authentic sensibility. Similarly, the developing romance between the two title characters, kept secret for obvious reasons, is handled with both grace and passion. I’m a bit less convinced about the magical tattoos, initially used simply as a way for Kid Wolf to anticipate his opponents’ moves, but which, as in common in fantasy, seem to become more powerful as the plot requires. In a key fight, though, Kid decides he needs to forgo them in order to win on his own skills alone, which echoes a familiar sports-magic convention (think of the end of Damn Yankees). Intriguing as it is, the alternate-history timeline at times seems almost an afterthought. We learn that the 1929 stock market crash occurred, but exactly how and why the timelines diverge is never made entirely clear – was this literally the fight that changed history, and if so, how could the narrators know that? – and Miller’s alternate 1980s looks less like speculative extrapolation than wishful thinking. But there’s no arguing that the violent poetic-justice fate of the story’s convincingly despicable villains delivers the cinematic rush it’s intended to, that the classically noir setting is brilliantly realized, and that the mutual devotion between these two memorable narrators gives the whole tale the legend-like aura of classic romance.

Gary K. Wolfe is Emeritus Professor of Humanities at Roosevelt University and a reviewer for Locus magazine since 1991. His reviews have been collected in Soundings (BSFA Award 2006; Hugo nominee), Bearings (Hugo nominee 2011), and Sightings (2011), and his Evaporating Genres: Essays on Fantastic Literature (Wesleyan) received the Locus Award in 2012. Earlier books include The Known and the Unknown: The Iconography of Science Fiction (Eaton Award, 1981), Harlan Ellison: The Edge of Forever (with Ellen Weil, 2002), and David Lindsay (1982). For the Library of America, he edited American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s in 2012, with a similar set for the 1960s forthcoming. He has received the Pilgrim Award from the Science Fiction Research Association, the Distinguished Scholarship Award from the International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts, and a Special World Fantasy Award for criticism. His 24-lecture series How Great Science Fiction Works appeared from The Great Courses in 2016. He has received six Hugo nominations, two for his reviews collections and four for The Coode Street Podcast, which he has co-hosted with Jonathan Strahan for more than 300 episodes. He lives in Chicago.

This review and more like it in the December 2022 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.