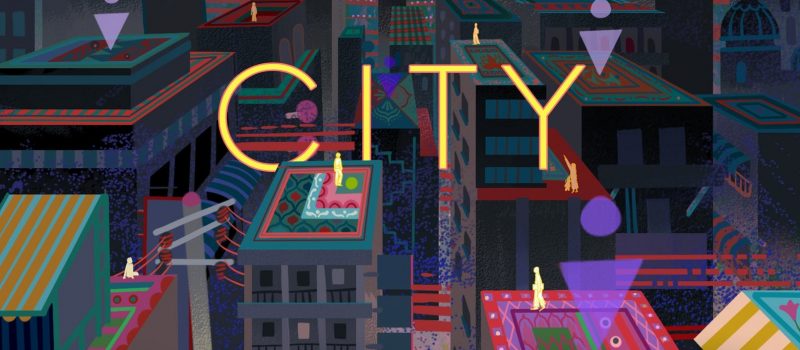

Gary K. Wolfe Reviews The City Inside by Samit Basu

Chosen Spirits, Samit Basu (Simon & Schuster India 978-9386797810, ₹499.00, 243pp, hc) April 2020. (Self-published, $3.99, eb) April 2020. As The City Inside, Samit Basu (Tordotcom 978-1-25082-748-7, $25.99, 256pp, hc) June 2022.

Chosen Spirits, Samit Basu (Simon & Schuster India 978-9386797810, ₹499.00, 243pp, hc) April 2020. (Self-published, $3.99, eb) April 2020. As The City Inside, Samit Basu (Tordotcom 978-1-25082-748-7, $25.99, 256pp, hc) June 2022.

Samit Basu’s The City Inside appeared in India a couple of years ago under the title Chosen Spirits, and was reviewed in this magazine (August 2020) by Ian Mond, who, while noting parallels between Basu’s grim near-future Delhi and recent Indian politics, expressed outrage that such a passionate and angry novel hadn’t yet been published outside of India. Now, thanks to Tordotcom, it has been, under a new title and apparently with some further revisions and rewrites by Basu. It quickly becomes apparent that Mond’s frustration was well-placed. While the novel does offer acerbic commentary on Indian politics, there are plenty of passages that sound unsettlingly familiar to the rest of us as well: when the protagonist Joey is complaining about her parents’ unwillingness to admit how much the world has changed, she unreels a litany that seems to get closer to home as we read it: ‘‘the repeated pandemic-wave collapses… the blasphemy laws in several states… the mass de-citizenings, the vote list erasures, the reeducation camps, the internet shutdowns, the news censors, the curfews… even the scary stories of data-driven home invasions….’’ This is not even to mention the ‘‘Years Not to Be Discussed’’, with its oxygen blockades and rivers full of corpses. Basu has said that his novel wasn’t conceived as a dystopia in the sense of a bleak future, and he has a point: it’s hardly the future at all.

Joey (short for Bijoyini) works as a ‘‘Reality Controller,’’ managing the social media feeds of ‘‘Flowstars,’’ corporatized influencers whose outsized cultural footprints combine the most unnerving aspects of current media platforms and cable news networks, even though Joey knows that ‘‘most public news is a lie’’ and that on the public ‘‘Fetch-boards’’ of the Flows, ‘‘the truth/absurd lie ratio is about 1/7.’’ Her most prominent client is a former boyfriend named Indi, and her daily life is complicated by trying to manage her out-of-touch and unemployed parents, her younger brother who wants to drop out of school, and an annoying self-help AI on her own feed who seems comically desperate to find ways to keep her happy.

Basu devotes so much attention to building a dense and detailed portrait of Joey’s world, from the effects of climate change to the marginalization of various groups to corporate malfeasance, that some readers might reasonably begin to wonder when the actual plot will show up, and when Joey will become something more than a passive player. The pace begins to accelerate once we are introduced to Rudra, the black-sheep scion of a super-wealthy family from which he has grown so alienated that he’s excluded from his own father’s funeral. When, after the funeral, Rudra’s creepy brother offers him a family position which amounts to managing a corporatized slave trade, Joey, a childhood friend, steps in and almost impulsively offers him a position with her Flow company. Aided by Rudra’s outsider perspective, we begin to gain a clearer view of the corporate politics of Joey’s job, meeting a variety of characters, including the Korean-diaspora Jin-Young who is her assistant, the rival Flowstar Zaria, the ambitious Tara, and most notably the power-obsessed executive Nikhil, who in one of the more brilliantly ironic lines in the novel tells Joey that ‘‘We think the idea of truth is due for a comeback, and we want to be its personal manager.’’ (Have ‘‘mad scientists’’ in SF been completely replaced by ‘‘mad corporate execs?’’) The schemes and counterschemes that unfold expand the scope of the tale exponentially, even leading to a vision of a posthuman future far more chilling than the world we’ve already almost become accustomed to. A final chapter titled ‘‘Deleted Scenes’’ (an addition to the American edition) adds still more depth and resonance to Basu’s extraordinary vision of an urban future that isn’t nearly as remote as we might want it to be, and that is yet the latest example of what seems to be a remarkable period in Indian and South Asian SFF.

Gary K. Wolfe is Emeritus Professor of Humanities at Roosevelt University and a reviewer for Locus magazine since 1991. His reviews have been collected in Soundings (BSFA Award 2006; Hugo nominee), Bearings (Hugo nominee 2011), and Sightings (2011), and his Evaporating Genres: Essays on Fantastic Literature (Wesleyan) received the Locus Award in 2012. Earlier books include The Known and the Unknown: The Iconography of Science Fiction (Eaton Award, 1981), Harlan Ellison: The Edge of Forever (with Ellen Weil, 2002), and David Lindsay (1982). For the Library of America, he edited American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s in 2012, with a similar set for the 1960s forthcoming. He has received the Pilgrim Award from the Science Fiction Research Association, the Distinguished Scholarship Award from the International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts, and a Special World Fantasy Award for criticism. His 24-lecture series How Great Science Fiction Works appeared from The Great Courses in 2016. He has received six Hugo nominations, two for his reviews collections and four for The Coode Street Podcast, which he has co-hosted with Jonathan Strahan for more than 300 episodes. He lives in Chicago.

This review and more like it in the June 2022 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.