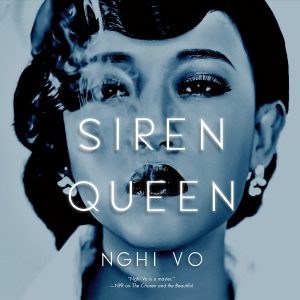

Gary K. Wolfe Reviews Siren Queen by Nghi Vo

Siren Queen, Nghi Vo (Tor 978-1-25078-883-2, $26.99, 288pp, hc) May 2022.

Siren Queen, Nghi Vo (Tor 978-1-25078-883-2, $26.99, 288pp, hc) May 2022.

From Nathanael West to Tim Powers, the vision of Hollywood as a kind of hallucinogenic inferno of ambition, lust, corruption, and betrayal has nearly become a literary convention, both in fiction and nonfiction. While most novels about Hollywood history succumb to the temptation to name-check real-life movie personalities, even if only as walk-ons, Nghi Vo’s Siren Queen reverts to the narrative strategy of West’s classic The Day of the Locust, inventing all the characters while keeping in place the broad outlines of the movie industry. Though set mostly in the Hollywood of the 1930s, Vo’s novel never mentions any actual movie stars or producers, or for that matter any historical figures; even events such as the Chinese Exclusion acts or the Depression only get passing mention. Nor is the novel any sort of roman à clef. While we could probably track down parallels between Vo’s central character, Luli Wei, and that of the early Chinese-American star Anna May Wong, and while Vo’s three competing studio moguls inevitably suggest figures like Thalberg, Mayer, and Selznick, the hermetic and haunted Hollywood of Siren Queen is very much Vo’s own territory – and a pretty creepy place it is.

We first meet Luli as a young girl living with her sister and parents above their laundry, sneaking off to the local movie theater whenever she can. Stumbling into an actual movie location in 1932, she finds herself recruited for a brief walk-on role, and even meets a Mexican-born movie star, whose ‘‘exotic beauty’’ roles are a foreshadowing of Luli’s own later challenges. She comes to the attention of a predatory director named Jacko and essentially blackmails him into setting up a meeting with the powerful studio head Oberlin Wolfe. Luli’s resistance to stereotypical roles limits her career early on, but eventually she gains fame as a monstrous Atlantean snake-lady called the Siren Queen, in a series of films that sound credibly like Universal efforts from the period. While she does find allies and eventually lovers – a more sympathetic director, a Swedish actress who becomes her roommate, an ingenue starlet with whom she has her first love affair, a screenwriter forced to conceal her identity behind a male pseudonym – she also learns that trying to negotiate a career as an independent-minded queer Asian-American woman is only part of the battle. Hollywood, it seems, is entwined with all sorts of Dark Forces and eldritch practices, ranging from apparent human sacrifice to the possibility of literally becoming a star in the firmament above Los Angeles.

Simply on the basis of its memorable characterization, elegant style, and a vividly detailed sense of place, Siren Queen might work pretty well as a mainstream novel. Vo initially doesn’t foreground her more outré elements, and readers who feel that magical systems should be laid out like Ikea diagrams might initially feel a bit at sea. But Vo’s deployment of fantasy is refreshingly ecumenical. Luli’s own mother, for example, has a few tricks of her own, such as creating ghost dolls using a combination of Chinese tradition and Colorado ‘‘mountain lore.’’ That Swedish actress roommate turns out to be a Skogsrå, a kind of forest spirit born with a cow’s tail (which the studio cruelly amputated). Union workers employ colorful pseudonyms out of fear of what the studio might do with their real names, while Daphne Grove turns out to be not an actor, but a haunted wood. More important, the powerful studio head Oberlin Wolfe is possessed by ‘‘something far older, and far less human,’’ and a good deal of the power-brokering takes place not in offices, but during ritual Friday night fires where actors and directors set up their own often magical courts. Needless to say, these disparate elements begin to converge with each other and with a climactic moment of Lilu’s career in a vivid conclusion that should satisfy anyone in terms of spectacle, but that more importantly serves as a capstone to the dogged quest for self-determination that makes Lilu, a multiple outsider in a rigged system, one of the more appealing fantasy heroes of recent years.

Gary K. Wolfe is Emeritus Professor of Humanities at Roosevelt University and a reviewer for Locus magazine since 1991. His reviews have been collected in Soundings (BSFA Award 2006; Hugo nominee), Bearings (Hugo nominee 2011), and Sightings (2011), and his Evaporating Genres: Essays on Fantastic Literature (Wesleyan) received the Locus Award in 2012. Earlier books include The Known and the Unknown: The Iconography of Science Fiction (Eaton Award, 1981), Harlan Ellison: The Edge of Forever (with Ellen Weil, 2002), and David Lindsay (1982). For the Library of America, he edited American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s in 2012, with a similar set for the 1960s forthcoming. He has received the Pilgrim Award from the Science Fiction Research Association, the Distinguished Scholarship Award from the International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts, and a Special World Fantasy Award for criticism. His 24-lecture series How Great Science Fiction Works appeared from The Great Courses in 2016. He has received six Hugo nominations, two for his reviews collections and four for The Coode Street Podcast, which he has co-hosted with Jonathan Strahan for more than 300 episodes. He lives in Chicago.

This review and more like it in the May 2022 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.