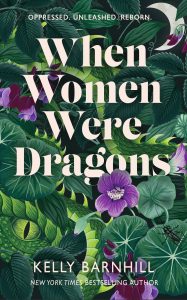

Gary K. Wolfe Reviews When Women Were Dragons by Kelly Barnhill

When Women Were Dragons, Kelly Barnhill (Doubleday 978-0385548229, $28.00, 352pp, hc) May 2022.

When Women Were Dragons, Kelly Barnhill (Doubleday 978-0385548229, $28.00, 352pp, hc) May 2022.

I suppose there are plenty of human-dragon metamorphoses in fantasy novels, but they aren’t what immediately came to mind when reading Kelly Barnhill’s first adult novel When Women Were Dragons – in which 642,987 American women suddenly transform into dragons on a single day in 1955. Instead, I was reminded of Ionesco’s 1959 play Rhinoceros, in which the residents of a small town all gradually turn into rhinoceroses. In Ionesco, though, the transformation was largely about conformity, whereas in Barnhill’s novel it’s very much about agency, about the relentless pressure of society to keep women and women’s lives ‘‘small,’’ as some of the dragon women put it. This may be one reason Barnhill chose to set her tale in the 1950s and early 1960s, a period in which the pressure cookers of feminism and civil rights were notably building up steam in the United States. Conformity does become another important theme for Barnhill, not so much in terms of the ‘‘dragoning’’ itself, as in the response to it from government, schools, and other institutions. The House Un-American Activities Committee retains its power well into the 1960s, all mention of the dragoning is expunged from schools and textbooks, and even scientists who attempt to study the dragons quickly find themselves blacklisted. In fact, with all the efforts to censor or suppress science, to ignore an obvious reality, to stigmatize a new population, and to simply pretend that change isn’t happening, it sounds more than a bit like our own era.

Barnhill is not particularly interested in the sort of formula standoff her main conceit might suggest; this isn’t Planet of the Dragons. Instead, the novel unfolds, rather surprisingly and wonderfully, as an almost Dickensian personal history; the subtitle of the first-person narrative-within-the-novel is ‘‘Being the Truthful Accounting of the Life of Alex Green – Physicist, Professor, Activist. Still Human. A memoir, of sorts.’’ Alex – her first small rebellion is calling herself that in defiance of her family’s insistence on Alexandra – is the daughter of a chilly, remote father (who turns out to be the real monster in the book) and a gifted mathematician mother, so beaten down that her talent only shows up in her skill with complex knots. The most rewarding part of Alex’s childhood is her colorful Aunt Marla, a former pilot and skilled auto mechanic whose life as a gay woman in the 1950s has its own challenges, and Marla’s baby daughter Beatrice, who becomes Alex’s beloved ward. After Marla transforms into a dragon and Alex’s mother succumbs to cancer, Alex finds herself not only Beatrice’s surrogate mom, but is also at the mercy of a disinterested father whose behavior is increasingly appalling and an educational system designed to oppress women. Only a sympathetic librarian and the love of her new girlfriend Sonja serve to mitigate Alex’s at times almost melodramatic miseries.

While Alex’s tale is the novel’s anchor, Barnhill also offers interspersed chapters which range from historical case histories of dragoning to transcripts of HUAC testimony. The case histories, ranging from classical antiquity to recent labor confrontations, are drawn mostly from documents written by one of those scientists whose research has forced him underground, Professor H.N. Gantz, who later becomes an important figure in Alex’s life. They not only provide a broad social and historical context for Alex’s story, but help prepare us for the latter parts of the novel, when the dragons themselves come to play an increasingly important, and increasingly controversial, role in society. It’s possible that some younger readers, viewing the 1950s and early 1960s as a period of bland conformity and sitcom fantasies, will be shocked at the implicit psychological violence directed again Alex as a budding mathematician and scientist – such as being called into the principal’s office in eighth grade because of consistently getting the top exam scores in math. ‘‘The boys see her loafing in class,’’ the principal, tells her mother, ‘‘and yet still claiming that top score, with no thought at all to their feelings. I ask you, what does one do with a girl with so little regard for others?’’ It’s the sort of scene calculated to trigger your own sense of rage, and Barnhill is consistently brilliant at making such scenes work, whether the instigator is a school administrator, Alex’s awful father, or a clueless politician in a Congressional hearing. While When Women Were Dragons is at center the frankly heroic story of Alex fiercely holding on to her educational dreams despite the monolithic forces aligned against her, it’s also a compelling fantasy that resists easy allegorization. At its best and most furious, it makes you want to breathe fire.

Gary K. Wolfe is Emeritus Professor of Humanities at Roosevelt University and a reviewer for Locus magazine since 1991. His reviews have been collected in Soundings (BSFA Award 2006; Hugo nominee), Bearings (Hugo nominee 2011), and Sightings (2011), and his Evaporating Genres: Essays on Fantastic Literature (Wesleyan) received the Locus Award in 2012. Earlier books include The Known and the Unknown: The Iconography of Science Fiction (Eaton Award, 1981), Harlan Ellison: The Edge of Forever (with Ellen Weil, 2002), and David Lindsay (1982). For the Library of America, he edited American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s in 2012, with a similar set for the 1960s forthcoming. He has received the Pilgrim Award from the Science Fiction Research Association, the Distinguished Scholarship Award from the International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts, and a Special World Fantasy Award for criticism. His 24-lecture series How Great Science Fiction Works appeared from The Great Courses in 2016. He has received six Hugo nominations, two for his reviews collections and four for The Coode Street Podcast, which he has co-hosted with Jonathan Strahan for more than 300 episodes. He lives in Chicago.

This review and more like it in the April 2022 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.