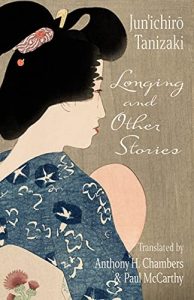

Caren Gussoff Sumption Reviews Longing and Other Stories by Jun’ichirō Tanizaki

Longing and Other Stories, Jun’ichirō Tanizaki (Columbia University Press, 978-0-231-20215-2, $20.00, 160pp, tp) January 2022.

Longing and Other Stories, Jun’ichirō Tanizaki (Columbia University Press, 978-0-231-20215-2, $20.00, 160pp, tp) January 2022.

One of Japan’s most celebrated and prolific authors of the last century, Jun’ichirō Tanizaki has remained relatively unknown in the West – a great loss for us, one that will be, hopefully, remedied by this new translation of Longing and Other Stories by Anthony H. Chambers & Paul McCarthy

It’s difficult to know how much of a translated piece’s artfulness can be attributed to the writer or the translator; in the case of the three stories in this slim volume, this reader believes the two roles act in concert. It’s obvious that Chambers and McCarthy are exceptional writers themselves, but they must have mined a rich vein in order to produce such gorgeous prose. The language is ornate, layered, and poetic, but only florid when it serves the plot. Even then, the language, the images, sing.

It’s a heady accomplishment. Tanizaki’s work is in dialogue with the Japanese experience of the early and middle 20th century, the clash and interplay of traditional culture and Westernization, and the growth of industrialization across the country (which would be sped up after WWII). Much of the cultural touchstones he uses are deeply embedded in Japanese culture, most, such as yōkai and oni, as well as classic social mores based on Confucian filial piety. Confucianism took root in Japan during the Heian and Muromachi periods, and was still strong through Tanizaki’s lifetime. Regardless of a reader’s familiarity with Japanese culture, Tanizaki’s stories are deeply human, universal stories of the struggles between children and parents, rendered with unflagging attention to minute details.

In ‘‘Longing’’, a child searches for his mother, traversing a nighttime rural landscape of haunted woods, empty roads, and a lonely hut occupied by an angry elderly woman. The story is terrifying – the environment is described in those aforementioned minute details, slowing the pace so that we feel as trapped and powerless as the small narrator. It’s also disorienting, because we are given no reason that this child would be out, alone, at night, and this alone builds terrific tension. At some point, we also realize that this being neither speaks or acts quite like a child, and the uncanniness (relieved, of course, at the twist ending) sustains the horror all the way through.

The second story, ‘‘Sorrows of a Heretic’’, switches moods, from horror to disgust, as we become intimately acquainted with Shōzaburō, a sometime-college student living in poverty with his parents and consumptive younger sister, O-tomi. Shōzaburō resents his position in life, sure that he is an undiscovered genius. But rather than apply himself to his studies or the welfare of his family, he steals and borrows (with no intention of paying back) money he spends on booze and women. We are powerless to do anything but watch Shōzaburō and the collateral damage he leaves in his wake. He’s awful, yet riveting, and readers are left wondering why it’s so delicious to watch someone else burn down their whole life – are we, also, awful?

‘‘Story of an Unhappy Mother’’ closes out the collection, and is the most alienating and moving of the three. The titular unhappy mother is unhappy in a very culturally-specific way. In the West, we characterize the ‘‘good’’ mother as one who puts their offspring’s best interests before their own. But this mother’s happiness and well-being are fed by how her children place her needs before their own, even when such actions are purely gestural (and everyone knows their emptiness). I had to remind myself many times during reading that this exemplifies Confucian filial piety that took deep root in Japan during the Heian and Muromachi periods, and was still strong through Tanizaki’s lifetime. However, as the story progresses, and a bizarre accident brings the mother’s ‘‘unhappiness’’ to a head, it’s clear that Tanizaki himself found the imposed responsibilities of Confucian philosophy problematic, and that when these responsibilities are imposed without context – without consideration for the individual and the moment – they can bring about deadly consequences. Though the story depends on, as I said, very specific cultural expectations, it’s about what children ‘‘owe’’ their parents, what parents should ‘‘demand’’ from their children, and what it means to be good to one another.

Horror doesn’t require gore. It doesn’t need jump-scares, monsters, ghosts, or demons. For a story to be truly frightening, it needs only people. They don’t have to be likable. We do not have to agree with their actions or decisions. But we have to see and recognize the fundamental humanness of these people, the honesty in their reactions, and to feel the loss of control and events unfold around them. Longing and Other Stories blends artful translation, gorgeous prose, and round, imperfect human people that are truly terrifying.

Caren Gussoff Sumption is a writer, editor, Tarot reader, and reseller living outside Seattle, WA with her husband, the artist and data scientist, Chris Sumption, and their ridiculously spoiled cat-children.

Born in New York, she attended the University of Colorado, the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Clarion West (as the Carl Brandon Society’s Octavia Butler scholar) and the Launchpad Astronomy Workshop. Caren is also a Hedgebrook alum (2010, 2016). She started writing fiction and teaching professionally in 2000, with the publication of her first novel, Homecoming.

Caren is a big, fat feminist killjoy of Jewish and Romany heritages. She loves serial commas, quadruple espressos, knitting, the new golden age of television, and over-analyzing things. Her turn offs include ear infections, black mold, and raisins in oatmeal cookies.

This review and more like it in the February 2022 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.