Russell Letson Reviews Belladonna Nights and Other Stories by Alastair Reynolds

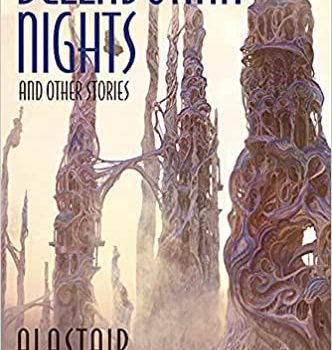

Belladonna Nights and Other Stories, Alastair Reynolds (Subterranean 978-1-64524-013-6, $45.00, 368pp, hc) October 2021. Cover by Marc Simonetti.

Belladonna Nights and Other Stories, Alastair Reynolds (Subterranean 978-1-64524-013-6, $45.00, 368pp, hc) October 2021. Cover by Marc Simonetti.

In Belladonna Nights and Other Stories, Alastair Reynolds gathers 15 stories originally published between 2011 and 2018, and adds one new story to this collection. In line with other Subterranean Press collections, the author supplies a context-setting introduction at the front and brief comments on each story at the back of the book. Even though I’ve been reviewing Reynolds for quite a while (in and out of the Revelation Space setting), the work in this volume is still a, um, revelation of sorts.

Much of Reynolds’s reputation rests on that long-running Revelation Space series or, recently, the Revenger trilogy: big books that tell big stories about large-scale adventures and conflicts – books often, not unreasonably, characterized as space operas. But the stuff of space opera can be married to less melodramatic, or even outright philosophical matters. What happens to human nature (physical and psychological) in the worlds where such epics can occur? What kind of physical universe generates that environment? How does one depict beings whose conditions of life and possible interests and motivations lie far beyond those of baseline humankind?

Evocations of scale are no surprise in Reynolds’s work – vast swaths of space and time, the deepest of deep histories, the most enormous natural and artificial structures, the longest of long lives – nor are extreme environments and varieties of personhood. All of that can be found in this volume, but squeezing it into the confines of a short story or novelette concentrates some emotional effects. Despite the kinds of heroic achievements that provide backgrounds for the novels – interstellar travel and settlement, longevity, expansion of human abilities – Reynolds’s shorter work often foregrounds a strain of melancholy, an awareness of ironies, an avoidance of simple optimism.

For example, the collection’s title story is set in the universe of House of Suns: a far, far future in which regular sub-lightspeed circumnavigations of the galaxy are the basis for the culture of the Lines of cloned post-humans called Scatterlings. At the end of every 20,000-year circuit, a Line will gather for a thousand-day reunion to celebrate, reintegrate, and literally share memories of wonders and adventures and projects. Despite their immense powers and longevity, though, neither individual Scatterlings nor even entire Lines are exempt from death, and this inevitably affects one such party in a way that surprises the viewpoint character.

“Different Seas”, set much closer to our own time, faces mortality in a dramatically different mode, as the solo on-board crew of a storm-wracked automated ship gets assistance from a “proxy” – the remote operator of a repair robot – with problems of her own. There are two endings to the drama, only one of them happy.

In “Death’s Door”, the tension is between near-immortality and ennui, with limits not on life but on novelty. Once you’ve done everything multiple times, in multiple bodies, in every corner of the solar system over a span of centuries, how do you stay interested in existence itself? I do confess that the narrator’s melancholy sounds a lot like clinical depression (Lazarus Long’s problem in Time Enough for Love). Or maybe he’s just more sensitive than his friends, who continue to find satisfaction in many-times-repeated experiences.

“A Map of Mercury” takes on the post-human condition from another angle. The cyborg Rhawn might be dedicated to the very human pursuit of making art, but her connection to mere meat humanity is almost completely severed – which does not prevent her from indulging in flights of Monty-Pythonesque insult aimed at Oleg, the organic human flunky sent to Mercury to negotiate with her. And she has not, she insists, given up anything that matters by abandoning her human body.

What use are lungs and a heart, on Mercury? What use is a digestive system? What use meat? These things are simply waiting to go wrong, waiting for their moment to fail us. To undermine our absolute, unblinking dedication to art. So we gladly discard that which the Collective fears to surrender. The flesh. Every organic part of ourselves.

Rhawn’s parting gift to her meat-based admirers is a demonstration of the transcendent, transhuman power of scorn and spite – as is Oleg’s audience response.

In “Sixteen Questions for Kamala Chatterjee”, pursuit of scientific knowledge is the driver of transformations far beyond standard humanity in a temporally scrambled storyline that had me thinking of Vonnegut’s Tramalfadorian view of a life. Here is the doctoral student at her dissertation defense. Here is the centuries-old, utterly transformed researcher, “this being that can swim inside a star.” Here is her graduate-school application. The story’s “atemporal” layout proves to be more than a narrative stunt, and the tale of Chatterjee’s exploration of the interior of the sun is filled with the kind of poetry-of-the-physical that marked the best of Poul Anderson’s work:

Finally, the first fixed bridgehead, the first physical outpost on the surface of the Sun…. A continent-sized raft of black water-lilies, floating on a breath of plasma, riding the surge and plunge of cellular convection patterns. Not even a speck on the face of the Sun, but a start, a promise… most of their physical structure dedicated to cooling – threaded with refrigeration channels, pumps as fierce as rocket engines, great vanes and grids turned to space….

Not all transformations are so extreme or Stapledonian. “Visiting Hours” is a kind of reworking of some of the materials of “A Mask of Mercury”, with a robotic body and telepresence allowing a paralyzed former mountain climber to find a new career as a high-steel architect. She refuses the opportunity to return to a repaired natural body, where she would be “Free to be hurt…. Free to be injured, free to be killed.” As a bonus, “Visiting Hours”, like “Different Seas”, constructs a background of a global economy and a working world remade by telepresence technology.

Three stories set in the Revelation Space universe point to its dark and melancholy side. “Open and Shut” is not so much a story as a report on an incident in the career of Prefect Dreyfus, a window into some very unpleasant corners of the libertarian-democratic Glitter Band culture, where “do as thou wilt” collides with necessary limitations, hard choices, and harder punishments. Dreyfus’s somber summing up: “If there’s one thing I’ve learned it’s that there’s always something worse.” The previously unpublished “Plague Music” features elements of horror, both in the details of the Melting Plague that will eventually destroy the Glitter Band and in the Poe-esque viewpoint character, whose backstory is only fully revealed after he has perpetrated his individual horrors. “Night Passage”, set in a different part of the Revelation Space future, is a merely grim (rather than horrific) drama of encounter with alien technology and familiar human ugliness.

Other stories mix, match, and repeat motifs and range across genre boundaries. “Wrecking Party” is a western with overtones of The Terminator. “The Lobby” is another horror story, but not like anything else in the book in its lack of tethering to a rational science-fictional background. “A Murmuration” has another Poe echo in its unreliable narrator, this time in a setting that implies a whole other SF story taking place around it. “For the Ages” is reminiscent of Greg Egan, with its very long-term cosmological vision and the extreme-engineering project of engraving a message for the ages on the surface of the diamond-crusted planet of a neutron star. In “Magic Bone Woman”, a threatened future needs the help of a human deep past that it has driven to the edge of extinction. “Holdfast” and “Providence” are both about sacrifice, and much of what matters (by way of motive and background) is not explicitly stated but (as with “A Murmuration”) sketched in.

Belladonna Nights is obviously not a complete map of Reynolds’s imagination, but a sampling that shows off its impressive range and some of its interconnections – the way that motifs, themes, tropes, SF ideas, and moods are combined, explored, and varied. It would be great fun to go through Reynolds’s notebooks, to see those raw materials before they get assembled into such compelling fictions.

Russell Letson, Contributing Editor, is a not-quite-retired freelance writer living in St. Cloud MN. He has been loitering around the SF world since childhood and been writing about it since his long-ago grad school days. In between, he published a good bit of business-technology and music journalism. He is still working on a book about Hawaiian slack key guitar.

This review and more like it in the November 2021 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.