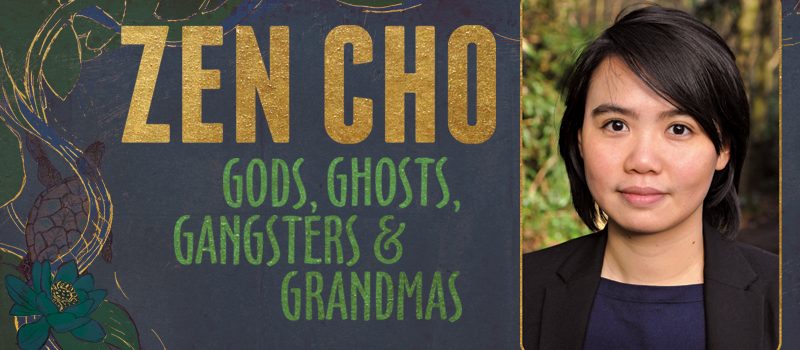

Zen Cho: Gods, Ghosts, Gangsters & Grandmas

ZEN CHO was born in Selangor Malaysia in 1986 and grew up in Malaysia, apart from a year and a half spent in the US around age six. She moved to the UK at 18 for university, where she met her husband. She earned a law degree at Cambridge, and now works as a lawyer. She lives in the UK with her family.

Cho began publishing genre fiction in 2010, with many stories collected in Spirits Abroad, published in Malaysia in 2014; it won a Crawford Award for Best First Fantasy. An expanded edition from Small Beer Press was recently published. “If at First You Don’t Succeed, Try, Try Again” (2018) won a Hugo Award for Best Novelette. Other notable shorter works include novellas The Terracotta Bride (2016) and The Order of the Pure Moon Reflected in Water (2020). She also edited anthology Cyberpunk: Malaysia (2015).

Her debut novel, historical fantasy Sorcerer to the Crown (2015), began the Sorcerer Royal series, which also includes The True Queen (2019). Black Water Sister (2021) is a standalone fantasy.

Excerpts from the interview:

“My collection Spirits Abroad came out in 2014 in Malaysia, published by a Malaysian press called Fixi, and was largely only distributed in Malaysia. The publisher is extremely successful within Malaysia. I also self-published an ebook that was available outside of Malaysia. That edition has gone out of print, so I was looking for a new publisher, and was very pleased when Small Beer Press agreed to take it on. The new version has been extended with more stories.

“It’s not a collection of everything I’ve written, but it has quite a lot. I left out a couple that aren’t very good or don’t have the rights available yet. It’s almost all my short fiction. It’s not that different from the first edition – it just has some new stuff that I’ve written since then. I don’t think I’ve changed all that much as a writer, in some ways. Black Water Sister, my new novel, could be described as “Spirits Abroad, the novel” – I did see a reader describe it as such. Spirits Abroad does exemplify the work I feel like I’m here to do. It took me that time and two novels to get to a place where I could write a novel that dealt with some of the same material that is addressed in Spirits Abroad.

“Black Water Sister is my third novel. It’s a standalone, not related to anything I’ve written before, except thematically. It’s about a young woman called Jessamyn who has spent most of her life in America, but her parents are from Malaysia. At the beginning of the book she is returning to Malaysia with her parents because the family have suffered a reversal of fortunes – the American Dream has gone a bit sour for them, so they’re going back to Malaysia. She’s under a lot of stress: she’s just out of college, she’s pretty broke, doesn’t have a job, doesn’t have a direction in life, and she’s got a girlfriend she doesn’t want her family to know about. Her parents are pretty stressed as well, so she feels like she has to be there for them. Then she starts hearing this voice in her head, and it turns out to be her estranged grandmother, who is dead. Her grandmother Ah Ma is a ghost, and in her life she worshipped the goddess the Black Water Sister, whose temple is being threatened by a development by a business magnate that Ah Ma has beef with. Ah Ma, she has very clear ideas of how she wants Jess to assist her, because like all ghosts she has unfinished business in the world of the living. Jess gets drawn into all these adventures involving gods, ghosts, gangsters, and grandmas – that’s my tagline for it.

“There are two quite clear sources of inspiration for the book. My first two novels, Sorcerer to the Crown and The True Queen, were set in Regency England, and they’re Jane Austen with dragons and people of color. While writing those books I spent a lot of time on Oxford English Dictionary online looking for old words, because the books are written in a quite deliberately archaic voice to fit their 19th-century setting. I particularly wanted to use the kinds of words that wouldn’t be familiar to most English speakers today, but would feel real, because they used to be used. Part of the point was to give readers the sense that, ‘Oh, this is a different world – this is a magical version of our world.’ In the course of my research, I came across this word ‘hagridden,’ which basically means stressed, but obviously has this literal meaning of being ridden around by a hag, i.e., a witch. I thought it was really interesting, and it immediately gave me this image of a young woman being ridden around by her terrible relatives, who I knew were supernatural in some way. That was one half of the idea.

“The other half of the idea came when I read The Way that Lives in the Heart by Jean DeBernardi, who’s an anthropologist based in Canada now. In the 1980s she went to Penang, which is an island in the north of peninsular Malaysia, and she did field research into Chinese folk religion as practiced there. I have quite a lot of family in Penang, and we used to go there every year for Chinese New Year, and I was brought up in this religious tradition. But my parents were really superstitious, and there’s a line in Black Water Sister about Jess’s parents, where it says, ‘Jess’s parents left the gods alone in the hope that the gods would do them the same favor.’ That was definitely my parents’ attitude to religion. They held religion at arm’s length. We might go to the temple and pray and stuff, but the framework was never really explained to me – what we were doing and why. What happened when I read this book was it gave me an intellectual framework for these beliefs I’d grown up with, and it was really interesting, rich in anecdote and story. When I read it, I thought, ‘There’s definitely a book in this.’ Black Water Sister is the combination of those two ideas, this idea of a young woman being ridden by this ghost, and the desire to explore this faith tradition of spirit mediumship and gods and so on. The last piece that gave the book its shape was the first line in the first scene, which really just came to me. It’s not substantially changed since then, which is rare for me, actually. The first line involves the spectral grandmother saying to Jess, ‘Does your mother know you’re a pengkid?’, which is a Malay word for tomboy, basically, or lesbian. That first line gave me the structure of the story. Although it’s got all these fireworks of dramatic confrontations with gangsters and gods and ghosts, it’s ultimately a story of Jess going on a journey to get to a place where she can give the answer she needs to that question.

“A lot of the dialogue is in Malaysian English. We call it Manglish, which I’ve always liked, because it sounds like ‘mangled English.’ It has a lot of loan words from Malay and Chinese – it’s English, but you mix in these words from other languages, and the grammatical structure is also based on other languages as much as English. That’s my first language, in a sense. I grew up speaking English at home, but it was Malaysian English, not British or American English. For me it’s very easy to write dialogue in it, because I’m basically like, ‘How would I say this, or how would my mom say it to me?’ At the time that I was writing the stories that ended up in Spirits Abroad, when I started writing original fiction set in Malaysia or about Malaysian characters, that was my breakthrough, in a way. Because even if you speak a certain language or a certain dialect, if you don’t see it in books and in writing – which generally doesn’t really happen with Manglish, it’s very much a colloquial, informal form of language – it can be quite difficult to come up with a literary form of the language, just because there’s that mental disconnect. Using that language was the breakthrough that then enabled me to write the stories in Spirits Abroad. By the time I was writing Black Water Sister, it was very natural to me to use Manglish when writing dialogue.

“The research in some ways is for small funny points. The first line, which I quoted earlier, has the word ‘pengkid,’ and I use that to mean lesbian, although it has a broader meaning than that, less specific. It’s a compromise using ‘pengkid,’ because Jess’s grandmother is speaking a form of Hokkien, which is a Chinese dialect that also uses a lot of Malay words. We call it Penang Hokkien – it’s really only spoken in Penang, and in Medan, Indonesia a similar form of Hokkien is spoken. I struggled because I didn’t know what word one would use to say ‘lesbian’ in Hokkien or in Malay, so I was asking around. I have a friend who is a Hokkien speaker and is a lesbian, and she was like, ‘Uh, I don’t know – there isn’t a word.’ In Malaysia it’s an informal language you use with your friends and family, but you wouldn’t use it at school or in writing, so there are going to be words that it doesn’t really have. Queerness is very taboo in Chinese and Asian cultures. I could have found a derogatory term for gay men – not that I would have been deliberately looking for specifically derogatory terms, but the term would have been derogatory. But for ‘lesbian,’ I really struggled. The research I did was more on that end. One very fair question a reader asked me is, ‘Would a Chinese grandma know and use the word pengkid?’ It is a very colloquial Malay term that you wouldn’t really expect a non-Malay, or even a Malay grandparent to be using, really. I just explained it in my head as Ah Ma being a very unusual grandma, which I think is a fair point.

“I don’t have any ideas for more books in that specific world. Black Water Sister feels so complete as a project, I don’t feel like there’s anything more I need to say about that particular set of characters, or that universe. I’m sure that I will return to the themes, just maybe in a different form, a different narrative, a different setting.

“I call The Order of the Pure Moon Reflected in Water ‘tropical wuxia.’ It’s a novella set in a secondary world that’s a mix of 1950s Malaya and the south China of wuxia. It follows a group you’re introduced to as bandits, but they’re not really bandits. They call themselves contractors – they do odd jobs, as it were. They encounter a nun whose temple has been destroyed, and she joins forces with them, and then they have adventures. I always think of it as my most misread book. There’s a trade review I’ve never been able to get over that describes it as being set in Tang Dynasty China, even though I think in literally the first two pages it refers to being on a peninsula. I find it really funny, because in terms of setting, it’s extremely confusing for non-Malaysian readers, because it’s a secondary world, but it’s also quite closely based on specifically mid-20th century peninsular Malaysia, but it just never says that. I find it very interesting seeing the reactions of Malaysian readers, as it’s also inspired by a very specific period of Malaysian history, which I’ll come onto in a second. Malaysian readers say, ‘Oh okay! It’s set in Malaysia, and it’s set during the Emergency, and it’s about the war between the government and the communist guerrillas.’ Obviously they get it, because they’re like, ‘That’s all there.’ Whereas the non-Malaysian readers are like, ‘Oh, this is a lot of fun,’ but I think the smarter ones realize, ‘There’s quite a lot I’m missing here.’ I have to say – this sounds mean – but the less smart ones don’t realize it’s not Tang Dynasty China. (That review wasn’t Locus – I wouldn’t be that tactless. Locus actually did two reviews of Order, both of which were very kind.)

“There’s always something to laugh about – that’s my worldview. The Order of the Pure Moon Reflected in Water is my silliest book, and it’s the one with the saddest setting. I was going to talk about the inspiration, and it’s two things. One is embarrassing, and one is really serious and worthy. I always think that’s a good combination. So the slightly embarrassing thing is, the initial seed for the story came from me getting really into Rogue One, the Star Wars movie, but particularly the two Chinese characters. They’re not Chinese in the film, because there aren’t Chinese people in the Star Wars universe, but they are played by Chinese actors, Donnie Yen and Jiang Wen, and their characters are brothers in arms, Baze and Chirrut. I really enjoyed their dynamic. They’re minor characters, but really fun, and they reminded me of the wuxia that I’d see on the TV growing up – these Chinese fantasies with lots of kung-fu fighting and roving fighters who stand up for the common people. I was quite interested in writing a story inspired by that, but one of them would be a nun whose temple had been destroyed, and then the other would be from a very similar background, but in a different line of work. I wanted to explore that dynamic. The idea didn’t gel until I was thinking about wuxia specifically. The framework for the setting for wuxia is this fantasy south China, but it’s not just fantasy; it’s based on Chinese history. Generally, there are these officials, and this government that’s extremely corrupt and you can’t rely on, and there are the people who are suffering. So the jianghu – the fighters – they go around righting wrongs and defending the common man, because no one else will.

“I’m really interested in the period of history called the Emergency in Malaysia, after WWII. Peninsular Malaysia was occupied by the Japanese during WWII for three years, and previously it was a British colony. The British lost against the Japanese, and they pulled out and left the Japanese to take over. While the Japanese were in occupation, there were obviously resistance fighters, the Malayan Peoples’ Anti-Japanese Army, and they were communists. They were largely ethnic Chinese, and they were organized – they had links to the Communist Party in China, and they got funded by the British while the war was ongoing, and they were given weapons and training and so on, and they fought the Japanese. The Japanese left when WWII ended, and the British came back. Then the guerrilla fighters were like, ‘Hold on, that’s not what we were fighting for. What we were fighting for was an independent Malaya. We object to imperialism from either side.’ It’s a really interesting period, because it’s so complex. It’s at a time when a lot of the Chinese in Malaysia didn’t identify as Malaysian, even though the Chinese community had been around for a while. Many of them wouldn’t necessarily have had citizenship rights, and in fact granting the non-Malay communities in Malaysia citizenship rights was a very fraught point of contention in the process of the independence of the country and the creation of the country. That explains why, for example, Malaysian readers have a very different perspective on the book than non-Malaysian readers, because there’s a lot of history behind it. In the national narrative and the history of the Emergency, independence was really reached by an agreement with the British, and the party that led Malaysian independence was the conservative right-wing party. Our first prime minister was literally a prince who went to Cambridge and so on. That left-wing movement has been consigned to history as the communist menace, and race also complicates things, because most of these communists who were fighting for an independent Malaya were Chinese. This is history I was learning about as an adult, because the history you learn in school doesn’t really tell that story. Popular media that is in any way sympathetic with the communist guerrillas is censored. Don’t get me wrong – they did commit atrocities, they bombed trains, they caused fatalities – but from their point of view, they were fighting a war, and many of them would say a war of independence. It’s the classic question – I think Terry Pratchett says this in Jingo: what’s the difference between a terrorist and a freedom fighter?

Interview design by Francesca Myman. Photo by iDJ Photography.

Read the full interview in the September 2021 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.