The Year of the Jackpot by Gary K. Wolfe

It should have been a good year for reading. Many of the usual distractions seemed to go on hold in the spring, and most of them never came back. What had previously been the most boring software to emerge from the corporate app world, Zoom, suddenly became a lifeline for many, especially those without pants, while a simple trip to pick up groceries began to feel like going out on patrol in Predator, or wandering through a crowd of body snatchers who look just like us. One of the most widely streamed films during those early months was the decade-old Contagion, which only reminded us of the halcyon days when it was still SF (at least Gwyneth Paltrow died in the first reel, whereas in our timeline she survived to give us Goop, which as I write is hawking a $75 Italian face mask). By the end of the year, Stephen King’s The Stand was back as a TV series even longer than the one back in 1994; like COVID, it’s probably not yet over even as you read this. People dug out their old college copies of Camus’s The Plague or Defoe’s Journal of the Plague Year, and asked themselves whether rereading Connie Willis’s Doomsday Book was really such a good idea under the circumstances. At least three different projects solicited stories for a new Decameron (since its frame involved hiding out from the plague in Florence), the most relevant to our purposes here involving the redoubtable Jo Walton. But when I spoke with dozens of authors during a long series of daily Coode Street podcasts, I came away with the impression that the most popular COVID-relief reading was Martha Wells’s delightful Murderbot series, which finally added a full-length novel with Network Effect.

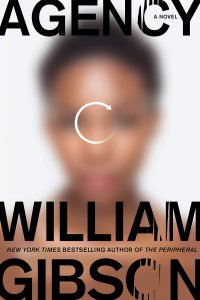

My own reading, as always, was largely governed by review deadlines, so I’ll begin with the usual disclaimer that I simply didn’t get to a number of important books, and that omitting them here is in no way a value judgment. In SF novels, the year began with one of its highest-profile titles, William Gibson’s Agency, a sort of sequel/prequel to 2014’s The Peripheral and supposedly the middle volume in the Jackpot Trilogy. Although, like the previous novel, it involved such traditional SF devices as alternate-history “stubs” being manipulated from the 22nd century, what became especially striking was Gibson’s notion of the Jackpot, a cascade of catastrophes that ends up killing off about 80% of the population. (I always suspected the term alluded to Heinlein’s “Year of the Jackpot”, which described another set of convergent apocalypses.) Although Gibson doesn’t particularly focus on wildfires, hurricanes, police murders, viruses, or loony presidents, it still felt like that sort of a year. Back in The Peripheral, though, Gibson did list as a contributing factor to the Jackpot “diseases that were never quite the one big pandemic but big enough to be historic events in themselves.”

My own reading, as always, was largely governed by review deadlines, so I’ll begin with the usual disclaimer that I simply didn’t get to a number of important books, and that omitting them here is in no way a value judgment. In SF novels, the year began with one of its highest-profile titles, William Gibson’s Agency, a sort of sequel/prequel to 2014’s The Peripheral and supposedly the middle volume in the Jackpot Trilogy. Although, like the previous novel, it involved such traditional SF devices as alternate-history “stubs” being manipulated from the 22nd century, what became especially striking was Gibson’s notion of the Jackpot, a cascade of catastrophes that ends up killing off about 80% of the population. (I always suspected the term alluded to Heinlein’s “Year of the Jackpot”, which described another set of convergent apocalypses.) Although Gibson doesn’t particularly focus on wildfires, hurricanes, police murders, viruses, or loony presidents, it still felt like that sort of a year. Back in The Peripheral, though, Gibson did list as a contributing factor to the Jackpot “diseases that were never quite the one big pandemic but big enough to be historic events in themselves.”

Fortunately, the other excellent SF novel I read at the beginning of the year, and one of the outstanding debuts of 2020, was Simon Jimenez’s lyrical and moving space opera The Vanished Birds, which earned glowing reviews despite being initially marketed in a way that seemed intent on downplaying its SF content. I hope it still retains enough visibility to show up on the awards ballots where it belongs. Two other fascinating debuts were Hao Jingfang’s Vagabonds, translated with his usual grace by Ken Liu, an almost leisurely coming-of-age novel concerning philosophical young moon colonists, which served as a pointed reminder that not all Chinese SF looks like Cixin Liu, and Gautam Bhatia’s The Wall: Being the First Book of the Chronicles of Sumer, with its evocative science-fantasy setting (in the far-future, Gene Wolfe sense) of a society isolated by a giant wall and the young people who challenge its orthodoxy.

In the spring, two SF novels drew my attention not only because of their brilliance, but also because they seemed to receive less attention in the US (and were less widely available) than they deserved to be. Paul McAuley has forged one of the most distinguished careers since the 1980s, but War of the Maps, with its almost archetypal plot and its stunning, epic setting (the exterior of a Dyson sphere!) represented yet another new direction for one of Britain’s leading figures. James Bradley, who has become in both fiction and non-fiction one of Australia’s eminent voices on climate change and culture, offered a particularly inventive and sly take on the issue with Ghost Species, which draws us in with a kind of techno-thriller about re-creating a Neanderthal child, but turns into a deeply humane and moving tale of coping with a radically shifting environment.

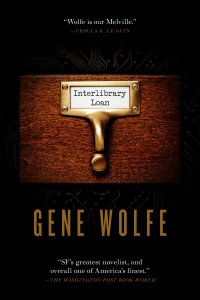

Summer and fall were full of goodies for fans of two of England’s most distinguished writers. Both M. John Harrison and Christopher Priest published new novels as well as retrospective story collections. Harrison’s The Sunken Land Begins to Rise Again was probably the finest literary novel I read during the year (note that I’m not qualifying that with the weaselly “literary SF”), with the self-absorption of its two main characters outpaced only by the disintegration of the world around them, while his collection Settling the World: Selected Stories 1969-2019 traces his career all the way back to the waning days of the New Wave, and might be a good introduction to his work for those wondering what the fuss has been about for the last 50 years. Priest’s collection Episodes was almost as comprehensive than Harrison’s, and contained some small masterpieces like “An Infinite Summer”. His novel The Evidence is as clever as any of his “Dream Archipelago” novels, combining the unpredictable shifts in time and space in that iconic setting with the tale of a cold-case murder investigation, all narrated by a writer of thrillers whom we’re not sure we should trust. Speaking of slippery narrators, I should mention that the summer also saw Gene Wolfe’s last novel, Interlibrary Loan, a sequel to 2015’s A Borrowed Man. While there is indeed a sad and valedictory tone to the novel, it would be a mistake to assume that Wolfe had given up his tricksterish ways in his tales of authors who can be checked out of libraries just like books. Finally, Michael Swanwick honored the memory of his friend, collaborator, and SF legend Gardner Dozois by completing City Under the Stars, a novel derived from an earlier novella and a novel idea that had stumped Dozois for years; the resulting tale of injustice and redemption sounds surprisingly like Dozois, if perhaps a bit less dark in its resolution.

Summer and fall were full of goodies for fans of two of England’s most distinguished writers. Both M. John Harrison and Christopher Priest published new novels as well as retrospective story collections. Harrison’s The Sunken Land Begins to Rise Again was probably the finest literary novel I read during the year (note that I’m not qualifying that with the weaselly “literary SF”), with the self-absorption of its two main characters outpaced only by the disintegration of the world around them, while his collection Settling the World: Selected Stories 1969-2019 traces his career all the way back to the waning days of the New Wave, and might be a good introduction to his work for those wondering what the fuss has been about for the last 50 years. Priest’s collection Episodes was almost as comprehensive than Harrison’s, and contained some small masterpieces like “An Infinite Summer”. His novel The Evidence is as clever as any of his “Dream Archipelago” novels, combining the unpredictable shifts in time and space in that iconic setting with the tale of a cold-case murder investigation, all narrated by a writer of thrillers whom we’re not sure we should trust. Speaking of slippery narrators, I should mention that the summer also saw Gene Wolfe’s last novel, Interlibrary Loan, a sequel to 2015’s A Borrowed Man. While there is indeed a sad and valedictory tone to the novel, it would be a mistake to assume that Wolfe had given up his tricksterish ways in his tales of authors who can be checked out of libraries just like books. Finally, Michael Swanwick honored the memory of his friend, collaborator, and SF legend Gardner Dozois by completing City Under the Stars, a novel derived from an earlier novella and a novel idea that had stumped Dozois for years; the resulting tale of injustice and redemption sounds surprisingly like Dozois, if perhaps a bit less dark in its resolution.

The fall saw three novels that seemed to speak to our present moment in very different ways, and which managed to do it without resembling each other at all. Cory Doctorow’s Attack Surface, the third novel in a trilogy that began with Little Brother back in 2008, was a moral parable reminding us of the ongoing dystopian potential of information manipulation in a year that had us preoccupied with other matters, but that increasingly began to look like Doctorow’s world. In Jonathan Lethem’s The Arrest, technology simply stops working, isolating people in their local communities, reminding us of what lockdowns might be like without Zoom or e-mail but, as usual, his real focus was on exploring morally ambiguous and mostly hapless characters. My candidate for the single most important novel of the year (it even made Obama’s favorites list!) is Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Ministry of the Future, which made the most effective use yet of Robinson’s fondness for meta-novelistic structures (whole essays, lists, and individual stories woven into a suspenseful central narrative) while combining a horror-story narrative of the hazards of climate change with an exhaustive catalog of things that can actually be done about it.

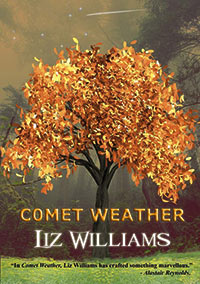

As usual, I read somewhat less fantasy, but it seemed to me that some of the most compelling fantasies of the year were strongly grounded in a sense of place – not the “worldbuilding” geographies of epic fantasy, but actual, recognizable settings that would work as well in mainstream fiction. The year got off to a great start with Liz Williams’s Comet Weather, a thoroughly engaging account of a Somerset family struggling to balance its magical heritage with getting by in contemporary Britain; to paraphrase Marianne Moore, encountering such thoroughly grounded characters in a sort of folk fantasy is like visiting imaginary gardens with real people in them. (The sequel, Blackthorn Winter, was reviewed here last month.) In a very different way, an authentic sense of place also defined the highest-profile fantasy novel in the early part of the year, N.K. Jemisin’s The City We Became, a lovely if tough-minded paean to New York’s five boroughs, combined with the threat of a Lovecraftian cosmic horror, even as some of the specific Lovecraft allusions seemed arbitrary. In the concluding volume of her Diabolists trilogy, Creatures of Charm and Hunger, Molly Tanzer moved the action to WWII Britain, and while part of the novel seemed familiar (good-diabolists-vs-supernatural Nazis), the novel was convincingly grounded in a Cumbrian farmhouse which also served as the main research library of the secret society of diabolists. Jo Walton’s unabashed love letter to Florence, Shakespeare, and fantasy, Or What You Will, despite its multiple time- and story-frames, was nearly detailed enough to serve as a travel guide (anyone who’s been to Florence will immediately recognize the landmarks and where they are situated).

As usual, I read somewhat less fantasy, but it seemed to me that some of the most compelling fantasies of the year were strongly grounded in a sense of place – not the “worldbuilding” geographies of epic fantasy, but actual, recognizable settings that would work as well in mainstream fiction. The year got off to a great start with Liz Williams’s Comet Weather, a thoroughly engaging account of a Somerset family struggling to balance its magical heritage with getting by in contemporary Britain; to paraphrase Marianne Moore, encountering such thoroughly grounded characters in a sort of folk fantasy is like visiting imaginary gardens with real people in them. (The sequel, Blackthorn Winter, was reviewed here last month.) In a very different way, an authentic sense of place also defined the highest-profile fantasy novel in the early part of the year, N.K. Jemisin’s The City We Became, a lovely if tough-minded paean to New York’s five boroughs, combined with the threat of a Lovecraftian cosmic horror, even as some of the specific Lovecraft allusions seemed arbitrary. In the concluding volume of her Diabolists trilogy, Creatures of Charm and Hunger, Molly Tanzer moved the action to WWII Britain, and while part of the novel seemed familiar (good-diabolists-vs-supernatural Nazis), the novel was convincingly grounded in a Cumbrian farmhouse which also served as the main research library of the secret society of diabolists. Jo Walton’s unabashed love letter to Florence, Shakespeare, and fantasy, Or What You Will, despite its multiple time- and story-frames, was nearly detailed enough to serve as a travel guide (anyone who’s been to Florence will immediately recognize the landmarks and where they are situated).

If all these novels depended in part on infusing magic into domestic settings, this was even more the case later in the year. Alix E. Harrow’s second novel, The Once and Future Witches, was as delightfully original as her first, but entirely different. Her New Salem may be an imaginary village in a kind of gender-flipped alternate history, but it’s grounded in real historical detail from the Gilded Age/suffragette 1890s, and her delightfully witchy Eastwood sisters confront everything from misogyny, to racism, to labor relations. Similarly, the 1922 Georgia of P. Djèlí Clark’s Ring Shout has all the gritty detail of an Alice Walker novel, as well as the actual history of The Birth of a Nation, into which Clark seamlessly inserts his lively tale of shape-shifting monsters, Southern folklore, and apocalyptic racism. Sam J. Miller’s The Blade Between is virtually a love-hate letter to his hometown of Hudson NY and the convincingly scary supernatural horrors he introduces are firmly grounded in the town’s odd history dating back to whaling days. One of a handful of fantasies to land on the general bestseller lists, V.E. Schwab’s The Invisible Life of Addie Larue is a secret-immortal-among-us romance that gains much of its charm from its settings of rural France, historical Paris, and contemporary hipster New York.

There were, of course, enough worldbuilding fantasies to satisfy an aspiring psychotic, and one of the most interesting fully invented settings I saw was in R.M. Lemberg’s first Birdverse novel, The Four Profound Weaves, a poetic tale set on a sparse desert world filled with a rich variety of genderfluid and nonbinary characters – sometimes facing rigid societal restrictions – but perhaps even more unusually featuring two protagonists already well past middle age. But certainly the most hypnotically immersive setting I encountered was from another bestseller, Susanna Clarke’s long-awaited second novel Piranesi, whose very title hinted at its labyrinthine interior setting (though it’s not about the historical Piranesi at all). The massive, rambling House with its almost endless halls and chambers – and which seems to have an ocean occupying its lower floors – is at once expansive and claustrophobic, and the relatively tiny cast of characters, initially only the naïve narrator Piranesi and the mysterious Other (along with 13 other corpses and skeletons) all suggest that there is more to this world than we or Piranesi understand, and that of course turns out to be the case as the story elegantly begins to unpack itself.

Although it doesn’t quite fit into any category, I’d be remiss in failing to mention one of the most purely enjoyable novels of the year, Lavie Tidhar’s By Force Alone, which reads very much like an Arthurian fantasy by someone who’s lost patience with Arthurian fantasies. With its punk, post-Brexit sensibility, its cavalier anachronisms, and genre-hopping that takes us everywhere from kung fu movies to Beowulf to the Strugatskys’ Roadside Picnic, it might well upset Arthurian purists, but is marvelous example of the anarchic possibilities of post-postmodern fantasy.

It was a pretty good year for story collections. In addition to the retrospectives from Harrison and Priest mentioned above, Ken Liu’s second collection The Hidden Girl and Other Stories appeared early in the year, returning to his favorite themes of family, cultural assimilation, racism, and the digital singularity, which he explored in several related tales forming a sort of meta-narrative of migration to cyberspace (and those left behind). Jane Yolen’s third collection for Tachyon, The Midnight Circus, focused on her darker work, which includes not only her stories of the Holocaust (of which only one is included) but her explorations of aspects of Jewish history (including her family’s own) and the more disturbing subtexts of folk materials, from mermaid tales to the goblin Redcap. The Postutopian Adventures of Darger and Surplus was the first collection of Michael Swanwick’s waggish tales of the dandyish talking dog Surplus and his strategically nondescript companion Darger in a surprisingly complex far future, which nevertheless is populated with easy marks for the pair’s con games. Other veteran writers with distinctive voices also produced interesting collections: the stories in Rick Wilber’s Rambunctious: Nine Tales of Determination reflected not only his well-known interest in sports, but his sensitive and insightful treatment of disabilities that are too rarely touched upon in SF/F, while Cat Sparks’s appropriately titled Dark Harvest offers a variety of mostly grim futures, often in a devastated Australia, populated by social outsiders and rejects who nevertheless turn out to be pretty competent at survival. The most fascinating debut collection I saw was Alaya Dawn Johnson’s Reconstruction, with its restless and inventive exploration of settings ranging from a vampire-ruled Hawai’i to a transformed Mexico City, to alien planets, and – in the strikingly original title story – the American Civil War.

It was a pretty good year for story collections. In addition to the retrospectives from Harrison and Priest mentioned above, Ken Liu’s second collection The Hidden Girl and Other Stories appeared early in the year, returning to his favorite themes of family, cultural assimilation, racism, and the digital singularity, which he explored in several related tales forming a sort of meta-narrative of migration to cyberspace (and those left behind). Jane Yolen’s third collection for Tachyon, The Midnight Circus, focused on her darker work, which includes not only her stories of the Holocaust (of which only one is included) but her explorations of aspects of Jewish history (including her family’s own) and the more disturbing subtexts of folk materials, from mermaid tales to the goblin Redcap. The Postutopian Adventures of Darger and Surplus was the first collection of Michael Swanwick’s waggish tales of the dandyish talking dog Surplus and his strategically nondescript companion Darger in a surprisingly complex far future, which nevertheless is populated with easy marks for the pair’s con games. Other veteran writers with distinctive voices also produced interesting collections: the stories in Rick Wilber’s Rambunctious: Nine Tales of Determination reflected not only his well-known interest in sports, but his sensitive and insightful treatment of disabilities that are too rarely touched upon in SF/F, while Cat Sparks’s appropriately titled Dark Harvest offers a variety of mostly grim futures, often in a devastated Australia, populated by social outsiders and rejects who nevertheless turn out to be pretty competent at survival. The most fascinating debut collection I saw was Alaya Dawn Johnson’s Reconstruction, with its restless and inventive exploration of settings ranging from a vampire-ruled Hawai’i to a transformed Mexico City, to alien planets, and – in the strikingly original title story – the American Civil War.

Of the handful of anthologies that I saw, including a couple of year’s bests, the reprint anthology of the year seemed inevitably to be Ann and Jeff VanderMeer’s The Big Book of Modern Fantasy, post-World War II follow-up to the previous year’s Big Book of Classic Fantasy. I didn’t get a chance to review it, but like its predecessor it did much to broaden the scope of fantasy literature beyond the familiar genre-oriented, Anglo-American bias. The most important original anthology of the year – a claim I’d gladly make even if it hadn’t been edited by a colleague and dear friend – was Jonathan Strahan’s The Book of Dragons, which not only featured an eclectic, multicultural, and multi-genre assembly of dragon tales, reminding us of the almost infinite writerly usefulness of one of fantasy’s oldest tropes, but was also among the most physically lovely books of the year, thanks to the artwork of Rovina Cai. Strahan’s earlier anthology Made to Order: Robots and Revolution did something similar with the classic SF icon, and, rather surprisingly, was one of the few books to celebrate the centennial of Karel Čapek’s R.U.R. On the other hand, the anthology that introduced me to the most interesting writers and perspectives new to me was the relatively modest (even free!) Africanfuturism: An Anthology, edited by Wole Talabi, which was also a persuasive argument that we might stop regarding “African SF” as monoculture and recognize that its many authors come from different nations and different backgrounds.

I’m barely qualified to discuss short fiction outside of the anthologies I’ve already mentioned, but I did have some favorite novellas. The year began with delightful contributions from established masters of the form, one in SF and one in fantasy. James Patrick Kelly’s clever King of the Dogs, Queen of the Cats combined elements of space opera, talking dogs and recalcitrant cats, and running off to join the circus, while K.J. Parker’s characteristically cynical, hilarious, and assiduously detailed Prosper’s Demon added to his ongoing mythology of an imaginary alternate early Renaissance Europe even more corrupt, if possible, than the one in the history books. A much newer voice, Nino Cipri in Finna, took us through a manic series of alternate worlds hidden in a thinly disguised Ikea store, combining multidimensional adventure with sharp consumer satire. Summer gave us Jeffrey Ford’s spooky but lovely paean to small towns, libraries, and old horror stories Out of Body, Tim Powers’s return trip to the magical London of The Anubis Gates with The Properties of Rooftop Air, and Zen Cho’s slyly feminist tribute to wuxia, The Order of the Pure Moon Reflected in Water, with its memorable bandit-nun as a central figure. In the fall, Aliette de Bodard returned us to her far-future Xuya universe, and in particular to the Scattered Pearls Belt of her earlier mystery/SF mashup The Tea Master and the Detective, with another mystery, Seven of Infinities, in which the detective is an almost courtly mindship and the client a young tutor whose visitor has mysteriously been killed.

I’m barely qualified to discuss short fiction outside of the anthologies I’ve already mentioned, but I did have some favorite novellas. The year began with delightful contributions from established masters of the form, one in SF and one in fantasy. James Patrick Kelly’s clever King of the Dogs, Queen of the Cats combined elements of space opera, talking dogs and recalcitrant cats, and running off to join the circus, while K.J. Parker’s characteristically cynical, hilarious, and assiduously detailed Prosper’s Demon added to his ongoing mythology of an imaginary alternate early Renaissance Europe even more corrupt, if possible, than the one in the history books. A much newer voice, Nino Cipri in Finna, took us through a manic series of alternate worlds hidden in a thinly disguised Ikea store, combining multidimensional adventure with sharp consumer satire. Summer gave us Jeffrey Ford’s spooky but lovely paean to small towns, libraries, and old horror stories Out of Body, Tim Powers’s return trip to the magical London of The Anubis Gates with The Properties of Rooftop Air, and Zen Cho’s slyly feminist tribute to wuxia, The Order of the Pure Moon Reflected in Water, with its memorable bandit-nun as a central figure. In the fall, Aliette de Bodard returned us to her far-future Xuya universe, and in particular to the Scattered Pearls Belt of her earlier mystery/SF mashup The Tea Master and the Detective, with another mystery, Seven of Infinities, in which the detective is an almost courtly mindship and the client a young tutor whose visitor has mysteriously been killed.

Toward the end of the year Lavie Tidhar returned with a sweet-natured novella, The Big Blind, which actually has nothing at all to do with SF in its tale of a poker-playing novice trying to save her monastery, but which oddly resonated with one of the most popular streaming TV shows of the fall, The Queen’s Gambit, with its chess-playing orphan. That show is only worth mentioning because it sent a lot of people back to the novels of Walter Tevis, one of which was The Man Who Fell to Earth, which in retrospect was one of the better SF novels of 1963 (and now maybe an impending TV series itself, according to some reports). The Tevis novel was pretty much completely ignored by SF readers until the Nicholas Roeg/David Bowie movie many years later, and this might serve as a cautionary reminder that those of us who set out to name the novel, or story, or anthology of the year in any given year might seem pretty astigmatic from the vantage point of a half-century later. I’ve been at this long enough to know that there is a non-zero probability that 2020 produced a genuine SF/F classic that I’ve never even heard of, but that may bob to the surface years from now. At which point, I will pretend to have known about it all along.

Toward the end of the year Lavie Tidhar returned with a sweet-natured novella, The Big Blind, which actually has nothing at all to do with SF in its tale of a poker-playing novice trying to save her monastery, but which oddly resonated with one of the most popular streaming TV shows of the fall, The Queen’s Gambit, with its chess-playing orphan. That show is only worth mentioning because it sent a lot of people back to the novels of Walter Tevis, one of which was The Man Who Fell to Earth, which in retrospect was one of the better SF novels of 1963 (and now maybe an impending TV series itself, according to some reports). The Tevis novel was pretty much completely ignored by SF readers until the Nicholas Roeg/David Bowie movie many years later, and this might serve as a cautionary reminder that those of us who set out to name the novel, or story, or anthology of the year in any given year might seem pretty astigmatic from the vantage point of a half-century later. I’ve been at this long enough to know that there is a non-zero probability that 2020 produced a genuine SF/F classic that I’ve never even heard of, but that may bob to the surface years from now. At which point, I will pretend to have known about it all along.

Gary K. Wolfe is Emeritus Professor of Humanities at Roosevelt University and a reviewer for Locus magazine since 1991. His reviews have been collected in Soundings (BSFA Award 2006; Hugo nominee), Bearings (Hugo nominee 2011), and Sightings (2011), and his Evaporating Genres: Essays on Fantastic Literature (Wesleyan) received the Locus Award in 2012. Earlier books include The Known and the Unknown: The Iconography of Science Fiction (Eaton Award, 1981), Harlan Ellison: The Edge of Forever (with Ellen Weil, 2002), and David Lindsay (1982). For the Library of America, he edited American Science Fiction: Nine Classic Novels of the 1950s in 2012, with a similar set for the 1960s forthcoming. He has received the Pilgrim Award from the Science Fiction Research Association, the Distinguished Scholarship Award from the International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts, and a Special World Fantasy Award for criticism. His 24-lecture series How Great Science Fiction Works appeared from The Great Courses in 2016. He has received six Hugo nominations, two for his reviews collections and four for The Coode Street Podcast, which he has co-hosted with Jonathan Strahan for more than 300 episodes. He lives in Chicago.

This review and more like it in the February 2021 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

©Locus Magazine. Copyrighted material may not be republished without permission of LSFF.