Karen Burnham Reviews Short Fiction: Mad Scientist Journal and Clarkesworld

Mad Scientist Journal Winter ’20

Mad Scientist Journal Winter ’20

Clarkesworld 1/20

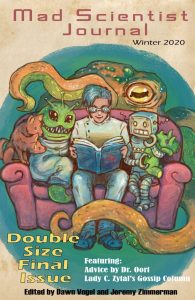

I am finally emerging into the dawning light of 2020 short fiction. Unfortunately, this winter brings the end of something fun and unique: with its 32nd issue and after eight years, the Mad Scientist Journal, a quirky quarterly, has closed its doors. Its conceit had always been stories specifically by and for mad scientists, and they cast the widest net possible within that remit. It has been a welcoming home for newer authors and established ones having some fun; very friendly to marginalized voices, especially LGBTQ, and just generally entertaining and thoughtful. The final issue is double sized with at least 29 stories plus an assortment of columns and flash pieces masquerading as want ads and equipment reviews. It does a great job of ending on a high note, showcasing just how broad a range the authors’ imaginations can encompass from such an ostensibly narrow prompt. Here you have a brilliant German scientist treated like a secretary by her colleagues; she quickly establishes a much more fruitful relationship with the alien they asked her to examine (“Stars Swimming in the Ether” by Genevieve McCluer). Over there you have wolves in Yellowstone starting to uplift themselves by maintaining fires and cooking food, and the park ranger who has to decide what to do about that (“Canis Ignis” by Cory Swanson). Horror readers will enjoy the surreally creepy sweetness of “A Home for Wayward Demons” by Megan Dorei, the denizens of which are also helping the main character with her mental illness. A cosplayer who uses a wheelchair is dating a potentially extraterrestrial mad scientist who uplifts an octopus to be her assistant; they eventually have to let it go its own way when it starts liberating others from aquariums (“Observations and Oversights on the Opportunistic Occupation of Octopuses in the Office” by Michael M. Jones).

There are classic takes on supervillains in such pieces as “Villainous Vowels: A Beginner’s Guide to Monologuing” by Alyssa N. Vaughn, and supervillain plots and schemes last even after they’ve been locked up and freed again in “Purely Mental” by Franko Stephens. There are even space pirate queens dodging assassination attempts in “Two and a Half Betrayals on Europa” by dave ring. And “Boned, Rolled, and Tied” by Darren Ridgley has the most humane description I’ve ever read of butchering a corpse for cannibalistic purposes in a post-apocalyptic world.

I’d like to give particular attention to the opening and closing stories, clearly chosen with care. The issue opens with “The Titan Through the Dust” by Joachim Heijndermans. It could be a facile concept: a young woman is on vacation in Singapore just happens to take an iconic photograph of a Godzilla-like creature rising up and crashing across the landscape. But the story unfolds much more seriously, with her career taking off in the aftermath but her mind continually drawn back to the other sights she saw that day, people she could have helped but didn’t, and the lasting effect of living through a catastrophe. The honor of closing goes to “Preliminary Field Observations of the Los Gatos Obelisk” by Cliff Winnig. The eponymous obelisk appears, hovering slightly above a road in California, and the narrator is a member of the California Institute for Extreme Archaeology team sent to investigate. Her journal entries become increasingly obsessed – at first constrained by dreams of tenure, but at the end not constrained by much of anything, normal physics included. There’s something to be said for leaving everything behind to follow a dream, no matter how mad it may seem. Thanks to editors Dawn Vogel & Jeremy Zimmerman for all the wild and crazy dreams made manifest within these covers over the years.

Once you’ve been reading a lot about mad scientists, you start seeing them anywhere. More than one story in January’s Clarkesworld could fit easily into that particular paradigm. For instance, in “Monster” by Naomi Kritzer, Cecily is in China, tracking down an old high school friend of hers. There are flashbacks to how she and Andrew bonded over science fiction and other pursuits; when she developed into a pioneering genetic engineer he got back in touch. What he did with her research is what brings her to Guizhou province, and the story develops in its own good time, culminating in a tightly intense ending. Meanwhile, Filip Hajdar Drnovšek Zorko brings us “The AI That Looked at the Sun“. Daedalus Station is inhabited by human scientists and computer routines alike, and some of them act more autonomously than others. The narrator of this story is one such subroutine that suffered from “acausal drift,” making friends with one of the researchers and attempting to carry out its own quixotic mini mission. The AI’s report on the ensuing incident is told with an interesting voice, changing over the course of the story. Rita Chang-Eppig imagines a future where most people have uploaded themselves into cyborg bodies, but that leaves others who, by accident or choice, can’t do so and are “The Last to Die“. They’ve been consolidated on one island that maintains a community suited to their fleshly needs, but what harmony they have is interrupted when a cyborg being moves in with her organically embodied ward. “Beth” and “Max” are clearly enigmas who, while polite, are not forthcoming about their motivations. The community splits in reaction to this perturbation.

January also brings us a new story by Chen Qiufan (translated by Emily Jin). “The Ancestral Temple in a Box” starts at a dying father’s bedside. He and his son have always clashed over approaches for the family business of carving amazing wood sculptures. The son imagined training robots to replace the skilled craftsmen they employ, something the father flatly rejects. When the son receives a mysterious box to open in VR, however, something more nuanced and interesting than a “Tradition vs. The Future” dynamic emerges. The end result is simply beautiful and beautifully described. “The Perfect Sail” by I-Hyeong Yun (translated by Elisa Sinn & Justin Howe) gives us a fascinating world where people can integrate versions of themselves that are about to die in different parallel universes. Chang Yeon has built herself an ostensibly perfect life this way, adopting multiple skills across a broad range of disciplines and making a lot of money as an entrepreneur. Now she has to decide whether to integrate a version of herself that has appeared among the Roo, a race of humanoids who are less than a centimeter tall and have only recently started exploring beyond their caves. We get Chang’s perspective as she rides her Lu, an amazing organism that operates at microscopic scales but incredible speeds. We learn about her journeys and her people’s history. She also must make a decision as the multiverse “sailors” offer her the choice to integrate with Chang Yeon. This story marks the end of the first round of funding for Clarkesworld‘s partnership with LTI Korea, so let me join with Neil Clarke in hoping that more funding will be found to bring more translations over from Korea. I’ve very much enjoyed this past year of discovering some of the best of their speculative fiction.

Recommended Stories

“An Ancestral Temple in a Box”, Chen Qiufan (Clarkesworld 1/20)

“The Titan Through the Dust”, Joachim Heijndermans (Mad Scientist Journal Winter ’20)

“Boned, Rolled, and Tied”, Darren Ridgley (Mad Scientist Journal Winter ’20)

“The Perfect Sail”, I-Hyeong Yun (Clarkesworld 1/20)

Karen Burnham is an electromagnetics engineer by way of vocation, and a book reviewer/critic by way of avocation. She has worked on NASA projects including the Dream Chaser spacecraft and currently works in the automotive industry in Michigan. She has reviewed for venues such as Locus Magazine, NYRSF, Strange Horizons, SFSignal.com, and Cascadia Subduction Zone. She has produced podcasts for Locusmag.com and SFSignal.com, especially SF Crossing the Gulf with Karen Lord. Her book on Greg Egan came out from University of Illinois Press in 2014, and she has twice been nominated in the Best Non Fiction category of the British SF Awards.

This review and more like it in the March 2020 issue of Locus.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.

While you are here, please take a moment to support Locus with a one-time or recurring donation. We rely on reader donations to keep the magazine and site going, and would like to keep the site paywall free, but WE NEED YOUR FINANCIAL SUPPORT to continue quality coverage of the science fiction and fantasy field.